Crimes of the Future (2022)

Enter the heart of darkness.

After 1999’s eXistenZ, it appeared body horror pioneer David Cronenberg all but abandoned his previous ground-breaking aesthetic to direct more straightforward dramas such as A History of Violence (2005) and Eastern Promises (2007). While both of these films are excellent, they proved a marked change in Cronenberg’s vision. With Maps to the Stars (2014) and Cosmopolis (2012) reviving parts of Cronenberg’s particular brand of fetishism and nihilism, fans hoped that his next work would prove to be a return to the sort of genre filmmaking that made the Canadian director so vitally important.

100vw, 616px” /></a><figcaption id=) Worshiping at the alter of flesh

Worshiping at the alter of fleshIn a shocking opening sequence, Cronenberg immerses the audience in his brave and terrifying new world. A young boy eats a plastic bin while hiding in the bathroom of his family home. His repulsed mother kills what she sees as her monstrous offspring and leaves his body for his estranged father, Lang Dotrice (Scott Speedman), to find. At this stage, we don’t know why the child hungers for plastic or how such a thing could come to be, which sets up the central mystery in the film.

Elsewhere we are introduced to the central players in the drama. Saul Tenser (played by Viggo Mortensen, who at this stage could be rightly called Cronenberg’s muse) and his assistant Caprice (Léa Seydoux) inhabit a retro-futurist space where Caprice (a former trauma surgeon) cares for Saul, whose body spontaneously creates new and surplus organs that do not exist for any practical biological reason. What the organs do supply is a way for Tenser and Caprice to gain celebrity as the surgery involved in the removal of the organs is made into performance art.

100vw, 616px” /></a><figcaption id=) Why can’t I be you?

Why can’t I be you?Tenser visits Dr. Nasatir (Yorgos Pirpassopoulos), who performs off-the-books surgical procedures. Tenser has a zip installed in his abdomen, which is fetishized by Caprice (who has also undergone her own surgical enhancements reminiscent of the real-life 90s performance artist Orlan). The new flesh is worshipped, surgery is sex, and Cronenberg reaches back into his genre bag of tricks to pad out his thesis.

Crimes of the Future comes from a script written in 1998, and in many ways, it shows. The film is filled with references to his earlier work, so much so that it is almost parodic at times. The fascinating plotline in the film doesn’t belong so much to Tenser and his associates but rather to cult leader Lang Dotrice who has convinced his adherents to undergo surgery so they can digest plastics. In both the diegetic world of the film and the real world, microplastics and environmental waste are causing mass contamination of food supplies. There’s a certain sense involved in trying to evolve the body to be able to consume readily available waste. Dotrice is in hiding from The New Vice Squad, who are trying to assassinate him. He holds something precious, the body of his son, who was born with the ability to digest plastic; an evolutionary step that was hitherto unknown. Tenser (for reasons that aren’t entirely clear) gets involved in the hunt for Dotrice and the shadowy world of corporate espionage married with law enforcement.

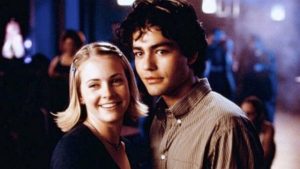

100vw, 616px” /></a><figcaption id=) Love for the inner beauty

Love for the inner beautyThe best part of Crimes of the Future is when it leans into its own absurdity. This is Cronenberg meets Kafka, and the result is bleakly funny as well as horrible in its implications. Timlin and Wippet are, in essence, comic characters, but as agents of bureaucracy, they’re also vaguely sinister. Stewart is fascinating as the starstruck Timlin, whose breathy lust for Tenser is played for laughs, but there is nothing funny about what Tenser is experiencing, and he rebuffs her with the line that he doesn’t do “the old sex.”

Confused plotting doesn’t aid a film that is surviving mostly through its grotesquery. It’s not that the audience is required to pay close attention to understand the themes of the film, they are evident, it’s more that Cronenberg’s script doesn’t lead anywhere in particular. If we calculate that we’ve seen more formidable and unnerving versions of his vision before and add to that writing that doesn’t completely work, we are left with a film that mostly serves as a reminder of how brilliant Cronenberg was. For many, that may be enough, to visit even a watered-down form of a master is still visiting a master.

100vw, 616px” /></a><figcaption id=) Fathoming the fangirl

Fathoming the fangirl3 / 5 – Good

Reviewed by Nadine Whitney

Crimes of the Future is released through Madman Entertainment Australia