The Black Phone (2022)

Never talk to strangers.

Denver, 1978: Young teenager Finney Blake (Mason Thames) is snatched by The Grabber (Ethan Hawke), a serial killer who has been preying on the local kids for a while now, leaving behind nothing but Missing Person notices and the odd black balloon. Locked in the murderer’s basement and with an unknown but surely ghastly fate waiting for him, Finney has only a disconnected black phone for company as he ponders his predicament. However, while the phone can’t reach the outside world, it can connect Finney with another one — the afterlife, from which the Grabber’s prior victims coach him on how he might best the Grabber and win some payback for all of them …

That’s a hell of a hook and more than enough for the average horror aficionado to give The Black Phone a spin. Add to that the fact that it’s based on a short story by fright-lit champ Joe Hill (Heart-Shaped Box, Horns), and reunites the Sinister (2012) team of writer C. Robert Cargill, director Scott Derrickson, and performers Hawke and James Ransone, and it’s a must-see.

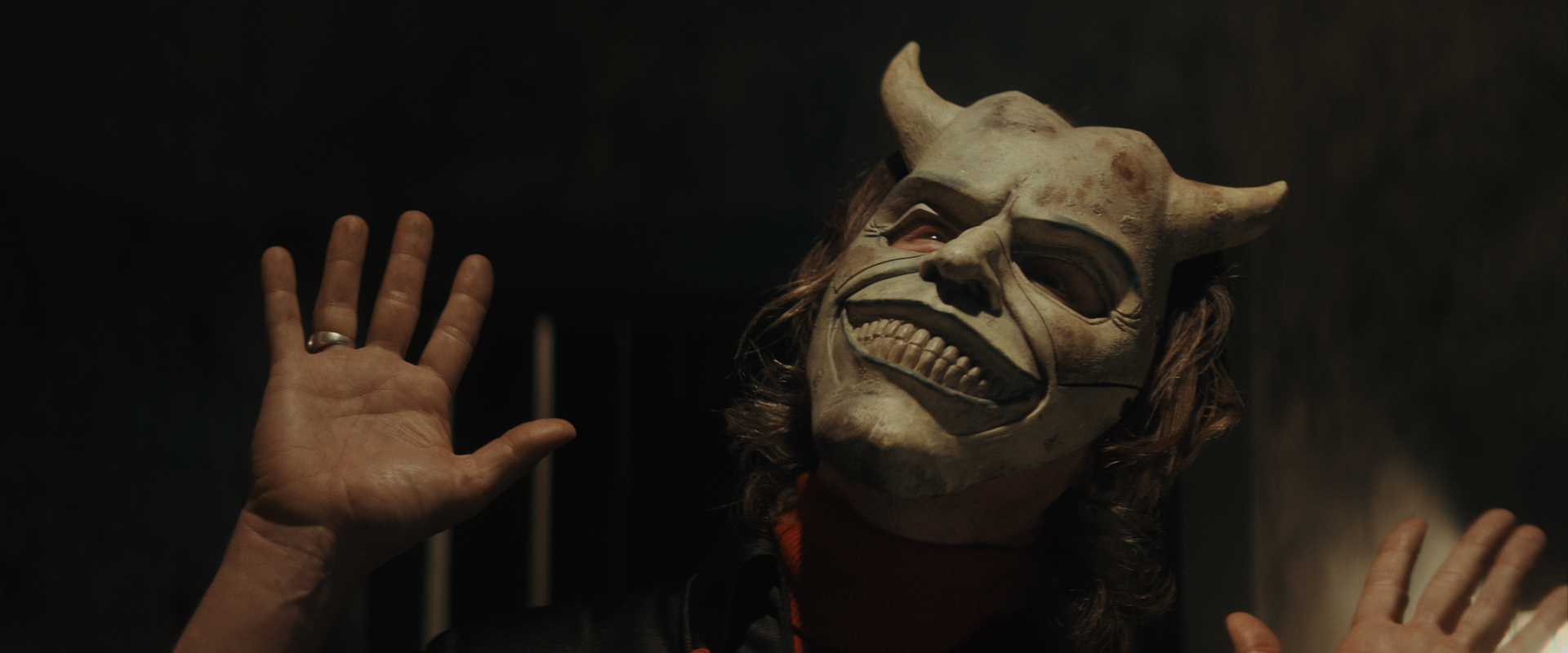

100vw, 616px” /></a><figcaption id=) Terror has many faces.

Terror has many faces.Cargill and Derrickson excel at evoking the tough, working-class, retro setting of the story. They both come from pretty rough backgrounds (as do I; I interviewed Derrickson around the time the first trailer dropped, and we talked about that), and their depiction of the society of children, what they get up to when their elders are not around and how they relate to (and beat, and bully, and … ) each other is on point. It’s interesting to me that people from Texas (Cargill), Colorado (Derrickson), and Western Australia (your humble scribe) can have so many comparable experiences. It’s also interesting how many people commenting on social media were taken aback by the casual violence and cruelty of these kids and the brutality of their home environments, but I can only say it rang true to me.

100vw, 616px” /></a><figcaption id=) Don’t hang up!

Don’t hang up!The thing is — and it’s a little thing, but it bugs me — that The Black Phone has not one but two avenues of largely unmotivated info dumps — the phone itself, where the eerie voices of murdered children can clue our kid in on vital data, and Gwen’s psychic visions. If the plot needs a bit of a hurry-along, we get a phone call or a psychic flash, which precludes the necessity of figuring out another way of getting the information across or moving the plot forward. It’s not a deal breaker — the inexplicable is a massive albeit not essential part of horror as a genre — but a film having two elements that perform this function seems excessive to me.

100vw, 616px” /></a><figcaption id=) Follow the voices …

Follow the voices …Here, Hawke is playful and sinister and downright terrifying when he needs to be, but he also communicates the sick vulnerability and neediness of the character (common to many serial killers, it’s worth noting). What could have been a one-note boogeyman bit in other hands, becomes something far more tangible and disturbing.

100vw, 616px” /></a><figcaption id=) ‘Would you like to see a magic trick?’

‘Would you like to see a magic trick?’4 / 5 – Recommended

Reviewed by Travis Johnson

The Black Phone is released through Universal Pictures Australia