Of the major aesthetic and narrative similarities of many streaming-first cinema offerings, the misuse of interior space and the standard episodic plotting are chief among them. Take for example films like Sophia Coppola’s On the Rocks or Ben Wheatley’s Rebecca. These movies, by filmmakers who are well above the quality and talent grade to be doing such simplistic fluff, could substitute for any number of pilot episodes of eventually canceled TV shows. That’s not to say they’re all trash, I thought On the Rocks was charming, but it is to say that there’s a different standard of filmmaking and different philosophy of visual storytelling that make streaming movies seem flimsier and hollower in thought and execution than theatrical films. Joseph Kosinski is another casualty of this, in his latest film Spiderhead, which has the dubious honor of releasing on your living-room television sets while his theatrical epic Top Gun: Maverick is still the movie to see at the cinema.

Visually Inert

There’s an obvious chasm between everything Kosinski was making before and Spiderhead. In Top Gun: Maverick, the charismatic and cheeky interplay between actors like Tom Cruise and Miles Teller comes off with such jubilant and raucous energy while in Spiderhead (which also features Miles Teller), Teller and Chris Hemsworth offer flat babble that wades in and out of interest and tension. In Oblivion, Kosinski (who also wrote the graphic novel) displays a brilliant sense of shock and terror in its twist, when (Tom Cruise) discovers a replica of himself in the vast expanse of a dead and empty world he’s exploring. The realization becomes such a jarring shift, a severe fissure out of nowhere that it totally changes the tone and feel of the entire film.

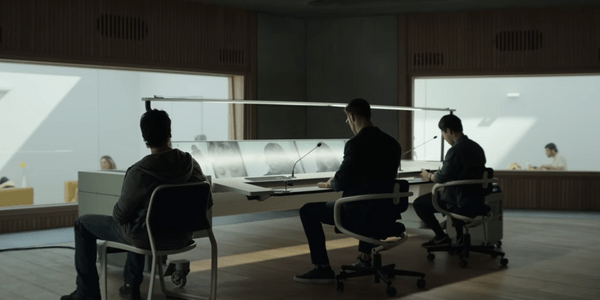

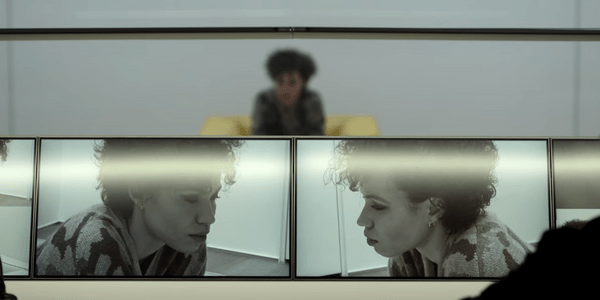

Whatever formal twists there are in Spiderhead – credited to George Saunder’s original short story Escape from Spiderhead for The New Yorker – are rendered thoroughly predictable in the movie, anticlimactic in its essential messaging, and resolved through a zero-stakes time-lapse that sweeps any doubt under the rug. The use of interior space in the movie is inert. Its clean white walls, its sleek hotel foyer-like setting, its spaceship bedroom accommodations are all ambiguously dull and comfortable. In contrast for example Alex Garland’s Ex Machina a movie with similar tense dynamics in a sleek enclosure and glass separating walls. There is a distinct transition from claustrophobia to openness in its interiors that augments the increasing dynamic tension between characters. Spiderhead’s characters, on the other hand, are awkwardly spaced out in the frame and operate under a casual medium shot or long shot that doesn’t reference them well in relation to each other – blocking is almost non-existent. But the movie’s narrative insists that there is a sense of entrapment, darkness, or illusion to the whole matter. None of this is successfully rendered visually.

Roots of a Good Story

It’s not all bad though. I have to give credit to the fact that Hemsworth’s Steve Abnesti character is a successfully irritating rendition of the modern tech bro. From a philosophical standpoint, the source material of Spiderhead is potent enough for metaphorical analysis of human behaviors and corrective sociology. A savvy research director named Steve Abnesti and his reluctant lackey Mark Verlaine (Mark Paguio) is part of a medicinal testing unit. They beta-test their pharmaceuticals on convicts in a new program that offers an alternative to jail time for people who have committed terrible crimes.

The different medicines are relegated through phone apps to administer different levels of pain, sexual arousal, and overall control. More than just tech guru pseudo-sciences and New Age gobble this movie’s (and story’s) premise also accurately stands in as a metaphor for the nefarious philosophies behind HR-department mandated social counseling. Both these industries address human problems through logic-programming of human behavior rather than appealing to natural human feelings.

Conclusion

It accurately depicts from a social analysis standpoint, the general problem with the New Age and top-down corporate thinking of human behavior and empathy. From theory this is fine, but it still has to be a movie, with a hook, and peril, and these emotions need to be translated visually. Instead what we get is something half-realized. Spiderhead is ironic – the characters are continuously being forced to feel strongly in a movie that remains emotionally inert. While it lacks visual allure and structural ingenuity, it is at least based on an interesting seed of an idea. George Saunders’ idea deserves a movie with more thought put into it.

Spiderhead is currently streaming on Netflix US.

Watch Spiderhead

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Join now!