There is something innate in the American character which inspires and deludes us of our place in history, past and present. Call it a devotion to American exceptionalism, cynicism, or opportunism, but even Senator Josh Hawley—the Missouri politician who spent months fermenting discontent and conspiracy theories about the 2020 presidential election, and who on the morning of Jan. 6, 2021 raised his fist in solidarity with a crowd of insurrectionists—seemed bewildered when the mob he played to actually stormed the barricades. There is footage of him fleeing for his life while Capitol Police officers like Brian Sicknick died defending the rule of law.

And yet, a little more than three years after that travesty, many are quick to smirk, shrug, or comfort themselves with the platitude of “it could never happen here.” Societal breakdown. Widespread political violence. Strongman authoritarianism. Civil war. In such a fog of complacency, Alex Garland’s latest film, titled simply Civil War, is not only a magnificent piece of cinema, but a cold, bitter ray of light which cuts through self-deceit. It imagines an apocalypse that isn’t science fiction but rather plausible speculation about where we could be five or 10 years down the road if the growing American dysfunction gets much bigger. And it captures this dread not through sensationalism or satire, or even for that matter much in the way of traditional commercial storytelling.

The dark brilliance of Civil War is Garland treats this subject matter as simply a character study on war journalists. It could take place in any other failed 21st century state, with its landscape of despair captured through the familiar, harsh, and unblinking gaze of a battlefield photographer’s camera aperture. It’s a recontextualization of America’s obvious fault lines through the prism most civilians are used to: the bleak yet somewhat staid and orderly framing of black and white photographs that might appear on an evening news broadcast any given night. But when these reports are coming from inside the house (even the White House by the movie’s end), the effect is at once eerie and clarifying. This isn’t a disaster or horror film; it’s a narrative of human carnage and suffering as we’ve come to internalize and normalize it in our collective imagination via something as mundane as a social media video.

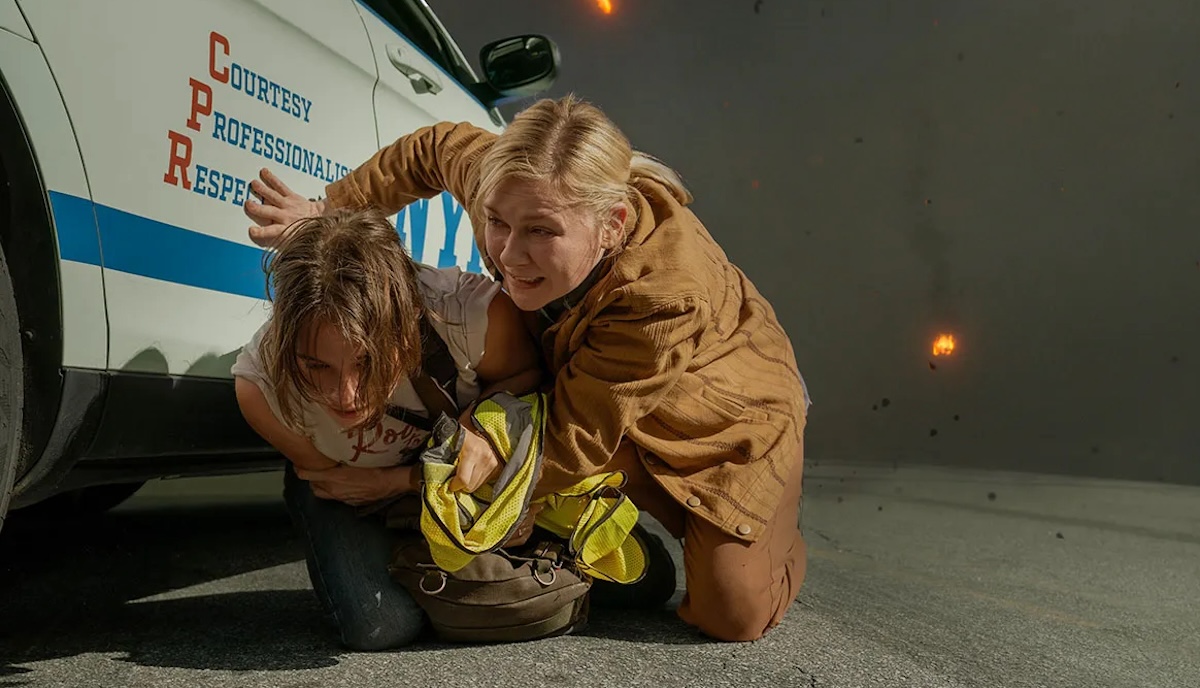

The folks recording those images are a quartet of war journalists at varying stages in their careers of staring into the abyss. Joel and Ellie (Wagner Moura and Kirsten Dunst) are the two sides of a coin that’s spent too many recent years living on the borderline. A classic adrenaline and war junkie, Joel has the half-crazed idea of interviewing the unnamed and tyrannical President of the United States (Nick Offerman) who’s seen the Union descend into total disarray after demanding a third term. In recent years, this POTUS has gotten into the habit of executing journalists, but with his government on the verge of collapse, and rebel forces inching ever closer to D.C., Joel is desperate to get the strongman’s final quotes before his remains are dragged through the streets like an all-American Mussolini.

Ellie is of steelier stuff. She simply wants to document the fall of an empire with the same detached gaze she perfected while lensing sectarian and imperial violence in the Middle East and Africa. She does, however, maintain enough of her soul to wince when Joel lets a cub photographer, the painfully young Jesse (Cailee Spaeny), tag along. Jesse idolizes Ellie and the legend she’s cultivated on the frontlines, but Jesse’s fresh face betrays how in over her head she’ll be when they start encountering bodies hanging from car washes, and killing fields in the land John Denver once dubbed “mountain mama.” They’re all cut of the same cloth though, and like their mentor, New York Times journalist Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson), they cannot sit by in the still smoking anarchy of New York City when there’s an actual battle unfolding on the outskirts of Charlottesville. So south they drive.

It is a shrewd choice by Garland to make his imagining of another American civil war focus not on the cause of the conflict, or even how the first shots were fired, but rather on its last bedraggled days. He avoids much in the way of exposition, including in the still perplexing nugget of information that California and Texas have joined forces to overthrow the government. Yet the scarcity of background works in the film’s favor. As Garland has already hinted to the press, it is disturbingly easy for any viewer to fill in the details of what occurred between today and this movie’s tomorrow; and by evading the political “hows” and “whys” of its scenario, Civil War is able to almost clinically analyze its speculative fiction with the banality of an AP stylebook.

The violence which occurs throughout the picture, both suddenly and randomly, is gruesome and matter of fact. Like most modern war films made in the past 25 years, Garland and cinematographer Rob Hardy utilize handheld photography to give an in-the-trenches tactility to the slaughter. However, Garland tweaks that Spielbergian standard by keeping most of the violence in clear and clean wide shots. When one American bleeds out on a dirty cement floor, the agony frozen by Jesse’s camera might have come from the scrapbook of Vietnam War photographer Eddie Adams, and the subsequent revenge killing of captured POWs certainly echo suspected Viet Cong officer Nguyễn Văn Lém’s execution on a Saigon street.

The chord Garland is striking is not subtle, but it comes through with the urgency of a carillon bell. This is what secession, disunion, and finally war would look like in America, and it’s as ugly as a red smear pooling beneath a pile of bodies. Who those Americans were and what differences they might have had will never be known by either the audience or the carrion birds about to feast.

The point is brutally made. What is more surprising is how much of a love letter the film becomes to journalists, particularly war correspondents. By structuring the film from their vantage, Garland has crafted a film that could be set in almost any collapsed state. He also lionizes a profession which has seen better days. This is best exemplified by Dunst’s taciturn performance. Underplaying every gesture, and seemingly throwing away each sparse line she’s handed, the actress quietly embodies the much remarked cynicism of a photojournalist who’s seen how too many sausages were made—and which in her case involved actual blood and guts. Yet her unremarked upon earnestness and hope for something better, if only gleaned through a wary gaze toward an unwanted protege, gives the movie its flicker of a soul.

That flicker will become a fire before the war is over.

Civil War is undoubtedly a movie that courts and will find controversy. The picture will be debated in news columns, dismissed by talking heads on cable, and reviled by some quarters of social media. Yet it is Garland’s most evocative and haunting work since Annihilation. And it achieves the queasy reaction it aims for. Even though there will be those who say it is alarmist and “could never happen,” the film comes out in the first presidential election year since the Jan. 6 insurrection, and the first since surveys showed more than a third of Americans indicated a “willingness to secede” from the Union. The threat of civil and institutional breakdown has risen in the last decade, and seems unlikely to abate when one party’s leader has already announced he’d like to be a dictator for “one day.”

Civil War enters this toxic maelstrom and deftly, brusquely asks its audience to stop the rhetorical and mental evasions. It is a towering piece of filmmaking, if you have the courage to sit through it.

Civil War premiered at SXSW on March 14 and opens nationwide in the U.S. and UK on April 12.

The post Civil War Review: Unforgettable Cinema If You Have the Guts to Watch appeared first on Den of Geek.