Ivan Sen, along with Justin Kurzel, John Hillcoat, and David Michôd are all part of a 21st century Australian cinema that delves into the dark corners of the sixth continent. From his most celebrated work Toomelah (2014) to his lates Limbo, Sen has amassed an impressive resume of sun-drenched, dusty, and barren crime films that feel like they all exist on a forbidden planet. His latest, Limbo, shot entirely in black-and-white is perhaps the most stark in the depiction of his country in these. Following the footsteps of Ted Kotcheff‘s landmark Australian masterpiece Wake in Fright (1971), the trope of the fish-out-of-water in over his head in a barren Outback town is exactly how this film goes.

A Reopened Murder Case

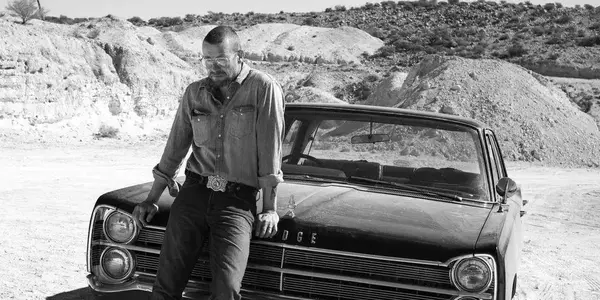

What separates Limbo from many other crime-mystery films like is that it finds its central detective figure, the rough and curt Travis Hurley (played by Simon Baker), to be a bumbling, clueless drug addict. It’s not that he isn’t a sympathetic character in ways, particularly related to his dark family life, but in general, he’s not the kind of protagonist who warrants any sort of benefit of the doubts. Because of this, Limbo starts off basically being a dead-end.

source: Dark Matter

Travis is investigating a reopened case about a young Indigenous Australian girl named Charlotte who was murdered in a remote town after being picked up on the highway. Travis goes around to several residents who were the last people who saw a young girl named, including her siblings Charlie Hayes (Rob Collins) and Emma (Natasha Wanganeen), and a man named Joseph (Nicholas Hope) who lives in a home carved out of an opal mine (called a ‘dugout’) and who’s brother Leon hosted parties where he’d invite Indigenous girls.

A Disorienting Landscape

The atmosphere and desolate quietness of Limbo is what keeps it interesting despite the plot following several predictable steps and anticlimactic turns. The choice to film the movie in Coober Pedy which is famous for its underground homes, bars, and stores, all carved out of the opal mines in the region, and the choice to film them in black and white, gives the film a totally extraterrestrial landscape and makes its ordinary mystery into a disorienting one. Simon Baker delivers a cold performance that threatens to border on emotionless and dry. He is so restrained, his character so straight-faced that it makes him an almost inconsequential presence in the face of the injustice that occurred. This could be intentional, that such a man is sent to reopen a murder investigation of an Indigenous girl – one who looks like he couldn’t care less.

source: Dark Matter

Conclusion

Sen films the movie in sparse establishing shots, which reflect the general stillness and quietness that pervades throughout the film. The presence of a gun, a heroin needle, or a tombstone cut through the banality from time to time, but Limbo tries to be the artfully subtle crime film. It succeeds in places – like when Emma and Travis bond in her home and the sexual tensions of the situation rise and collapse at a moments notice, without much words. It isn’t a movie that will grip you, and its focus on the injustice and neglect of Australian authorities on the lives and deaths of the Indigenous feel almost auxiliary to its need to build a brooding atmosphere.

Limbo was released in theaters in the U.S. on March 22, 2024

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.