Just two nights ago, I was struck by the sudden urge to watch Rapid Fire for the first time in more than a quarter of a century. I enjoyed it so much that I went straight in for a double bill and as soon as the credits rolled, I fired up Showdown in Little Tokyo.

Another revisit after years, when the movie had faded in my memory. It made me reflective, and harken back to a better time. A simpler time.

A brief, glorious window in the early 1990s when Hollywood greenlit movies based on a single sentence yelled across a cocaine-dusted conference table. Showdown in Little Tokyo exists purely because somebody but down a hooker long enough to hoover up a massive, thick line of Bolivian marching powder, and said out loud:

“What if Dolph Lundgren was a Japanese-culture expert… and Bruce Lee’s kid was the dumb American?”

Then everyone nodded, cut up another line, and the rest is history.

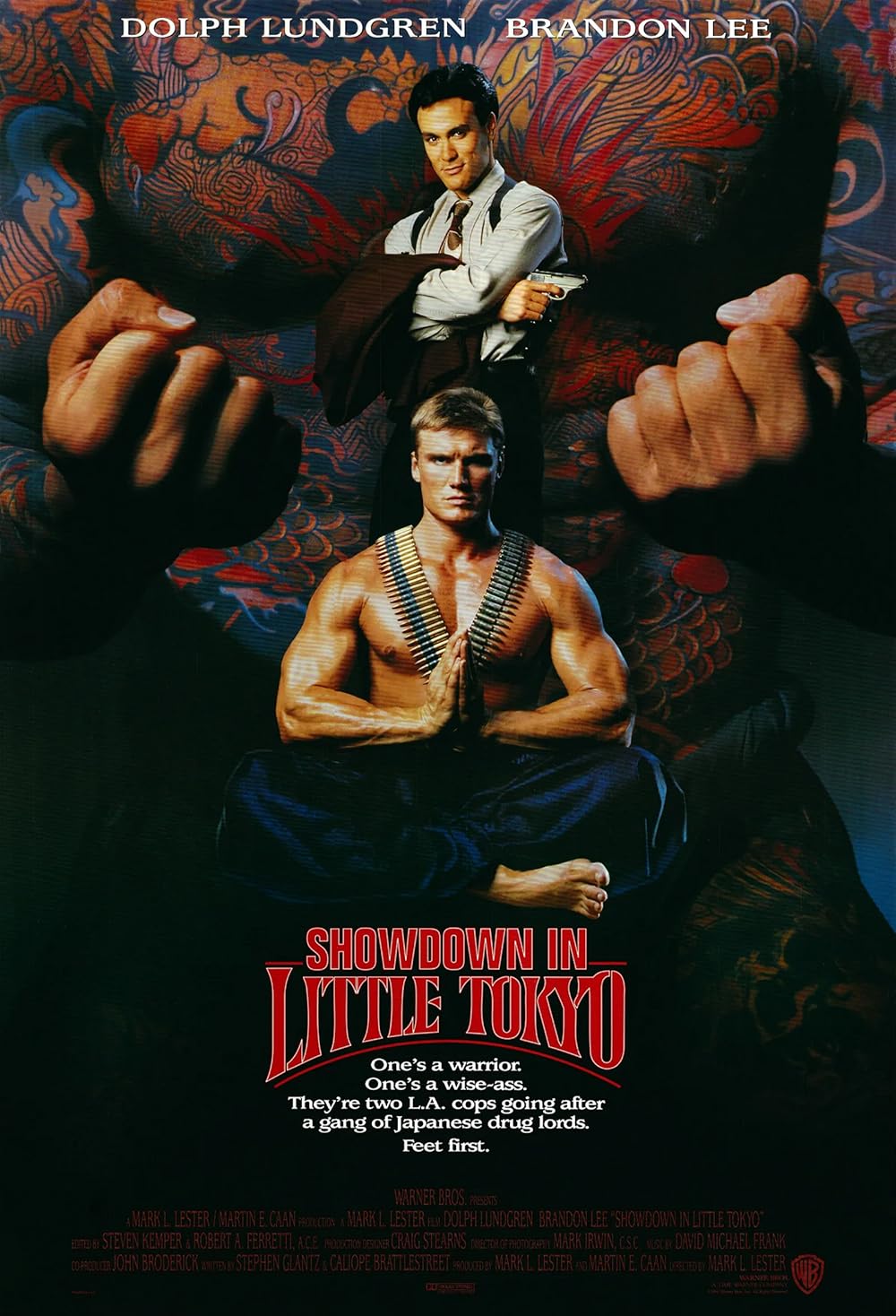

Showdown In Little Tokyo

This is not a movie so much as a vibe: neon-lit alleys, a sax stinger straight from rejected Miami Vice demos, and a buddy-cop dynamic so aggressively inverted it feels like a prank pulled on the audience and then never acknowledged again.

Dolph Lundgren plays Chris Kenner, an LAPD cop who was raised in Japan, speaks fluent Japanese, bows constantly, and understands the Yakuza better than the Yakuza understand themselves.

Meanwhile, Brandon Lee plays Johnny Murata, his partner, a loudmouthed, impulsive American who happens to be… Japanese-American, but completely clueless about Japanese culture. This reversal is treated as totally normal, which is how you know this movie could only have been made in 1991, before the internet developed opinions and before people started using the phrase “problematic” like it was a police siren.

Today, of course, the movie would be strangled in the womb by a thousand Medium articles bleating about “cultural appropriation,” “representation,” and “lived experience.”

In 1991? Nobodygives a shit. The casting logic is pure Hollywood Mad Libs: Brandon Lee is half Chinese in real life, but that’s close enough. Any Asian will do. Geography is a suggestion. Ethnicity is a mood.

And honestly? The movie is better for it.

The real joy of Showdown in Little Tokyo is how committed it is to the bit. Kenner isn’t just familiar with Japanese culture; he is obsessively immersed. He decorates his house like a samurai museum gift shop. He lectures criminals about bushido. He eats Japanese food with reverence, while Lee’s character chomps on burgers and rolls his eyes like a guy being dragged to a Renaissance fair by an ex-girlfriend.

Meanwhile, Murata, the character who should be the cultural bridge, is written as a standard-issue 90s cop: horny, reckless, sarcastic, and perpetually one bad joke away from an HR seminar. The movie never once stops to explain this dynamic. It just throws you into it and expects you to keep up.

This extends to their chemistry, which is pure mismatched energy. Lundgren plays Kenner like a Scandinavian monk who wandered into a Cannon Films production by mistake. Lee, meanwhile, is a live wire: quippy, smug, and constantly radiating “I’m going to be a huge star” energy. Which, tragically, he absolutely would have been.

Their relationship is punctuated by a recurring, imaginary but spiritually accurate comedy theme in the soundtrack. Every time they’re up to hijinks such as crashing through paper walls, threatening criminals, or exchanging banter that feels dubbed in from another movie, you can hear a wacky riff kicking in, like the score itself is saying:

“Uh-oh, the boys are at it again.”

Dolph Lundgren is the secret weapon here. Zen cop, and real-life killing machine. Lundgren plays Kenner with total sincerity. This is a man who fought Rocky Balboa, earned a master’s degree in chemical engineering, and is a real-life Kyokushin karate black belt. He brings all of that energy to a movie where he casually slices up Yakuza goons and then goes home to meditate.

Kenner’s most unintentionally hilarious moment comes near the end, when he decides that for the final showdown, regular clothes simply won’t do. No, sir. This is a karate fight, so he needs his karate clothes. He changes into his gi.

Not metaphorically. Literally.

The movie stops dead so Dolph Lundgren can get changed into his karate outfit, like a suburban dad putting on grilling shorts before firing up the Weber. It’s never explained. Nobody questions it. It’s just understood that if you’re going to have a climactic duel, you should dress appropriately, like it’s a themed dinner party.

And here’s the thing: because Lundgren actually knows karate, the movie lets him get away with it. He moves like someone who’s been doing this since before VHS. His kicks are high, clean, and terrifying. There’s no shaky cam, no fast cutting. Just a giant Swede folding people in half while the saxophone screams in the background.

Brandon Lee also stakes his claim to being the movie star we didn’t get to keep.

He is the heart of the movie, and watching it now comes with an unavoidable sadness. He’s funny, charismatic, and relaxed in front of the camera in a way that can’t be taught. You can see him figuring out his screen persona in real time: part action hero, part comedian, part smug little brother to Lundgren’s stoic big brother.

His death just two years later, during the making of The Crow, remains one of the great tragedies of modern cinema, not just because of who his father was – Bruce Lee, an actual mythological figure – but because Brandon was clearly on the verge of something special. He had the looks, the timing, and the self-awareness to survive the 90s action landscape and maybe even outgrow it.

In Showdown in Little Tokyo, he’s allowed to be silly, cocky, and occasionally overshadowed by Lundgren’s physical presence, which somehow makes him even more watchable. He doesn’t try to be Bruce Lee. He’s doing his own thing, cracking jokes, getting punched, and occasionally reminding you that, yes, he can absolutely wreck someone if the script demands it.

On their side is Tia Carrera, reminding everybody why she was the legitimate exotic smoke-show of the 1990s who could also just casually belt out a tune in real life.

Only As Good As A Bad Guy

Every good buddy-cop movie needs a villain. The more they chew the scenery, the better. This villain chews the scenery like it’s been covered in peanut sauce. Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa delivers as Yakuza boss Yoshida.

Tagawa, who sadly passed away recently, is phenomenal here. He has that rare ability to look genuinely dangerous while delivering dialogue that borders on comic-book nonsense. His presence elevates the movie from “dumb fun” to “dumb fun with teeth.”

From a deeply creepy scene of rampant voyeurism featuring a hooker called Angel who becomes literally half the woman her father would have wanted her to be, to monologues on honor, lineage, and revenge, he talks with the seriousness of a Shakespearean villain, even as the movie around him gleefully undermines any sense of realism.

This is a guy who doesn’t just want power. He wants thematic power. He’s the perfect foil for Kenner, as Yoshida is a man who understands Japanese tradition but uses it as a weapon rather than a philosophy.

The rest of the Yakuza henchmen exist primarily to be thrown through walls, impaled on swords, or kicked into oblivion by Lundgren’s size-14 feet, but that’s exactly as it should be. One of the joys of watching this movie is the sheer volume of the “Hey, it’s that guy!” moments as pretty much every 80s and 90s Asian extra and second-level actor appears in some capacity.

The result is a time capsule of glorious nonsense.

Showdown in Little Tokyo is the kind of movie that feels like it was assembled from spare parts of better films and then supercharged with testosterone. It’s violent, goofy, casually insensitive, and completely unbothered by how any of this might age.

And that’s the charm.

This is a movie where cultural reversal is played for laughs without apology, where a Swedish man is more Japanese than a Japanese-American character who is played by a half-Chinaman, and where nobody stops to explain or justify it. The movie just barrels forward, confident that you’ll either come along for the ride or get out of the way.

In today’s cinematic landscape, where every action movie is afraid of its own shadow, Showdown in Little Tokyo feels like a relic from a time when movies were allowed to be dumb, strange, and deeply entertaining without asking permission.

It’s not good, but it is fucking great.

The post Retro Review: SHOWDOWN IN LITTLE TOKYO (1991) appeared first on Last Movie Outpost.