Smokey And The Bandit, The Cannonball Run, hell – even Forrest Gump, there used to be a fine line in moves that seemed to be pure celebrations of Americana. Blue-collar people from less fashionable regions, frequently involving a road trip of some kind, doing unashamedly American things. I wondered where these movies went when, at the weekend, I found myself watching Every Which Way But Loose.

Released in 1978, and ostensibly an action-comedy film, Every Which Way But Loose was famously a big gamble for star Clint Eastwood. He was coming off the back of his highly successful Spaghetti Western period, and by now deep into Dirty Harry, with detours in movies like The Eiger Sanction, an offbeat comedy role raised some eyebrows.

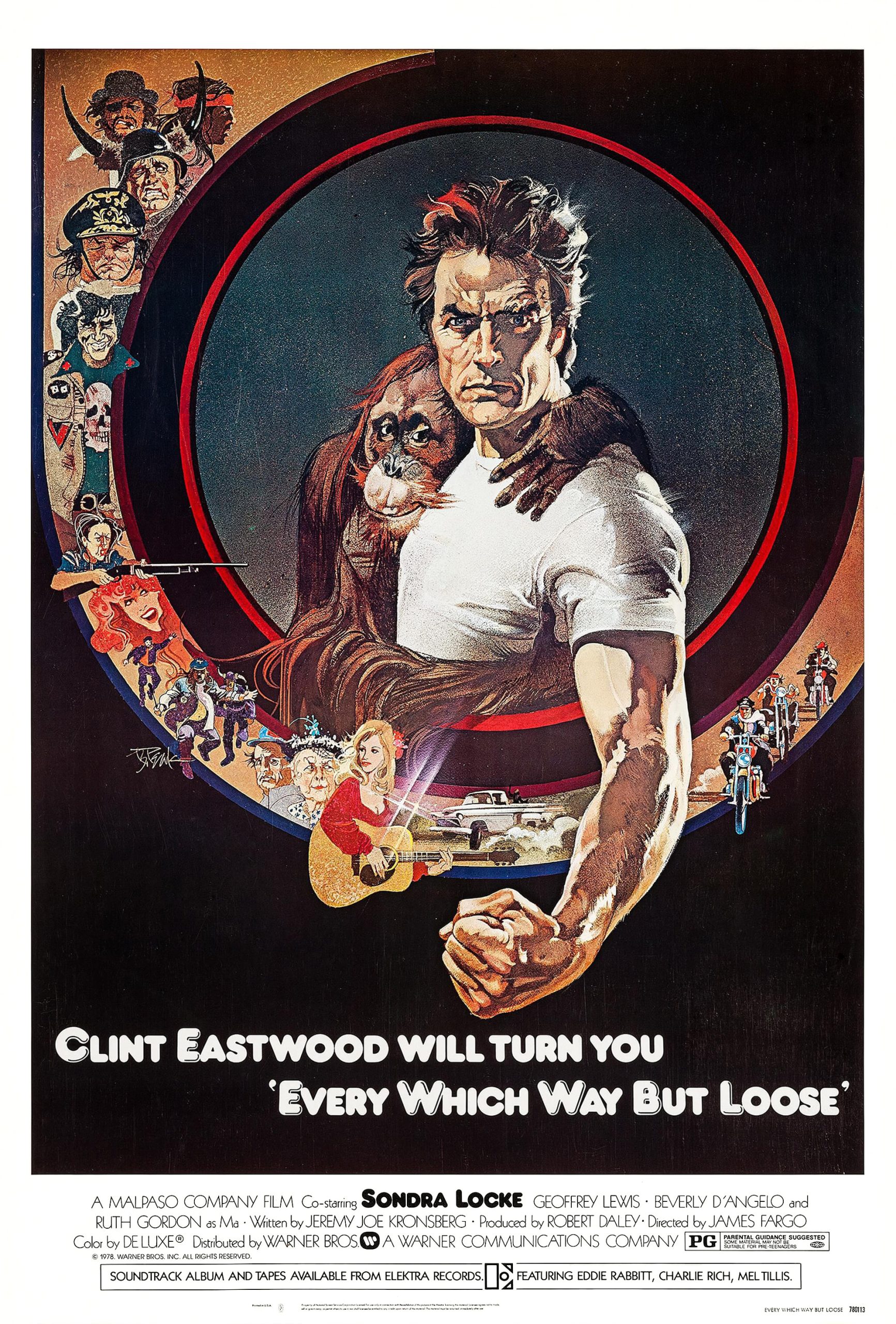

The script, written by Jeremy Joe Kronsberg, had been turned down by most big production companies in Hollywood. Eastwood unexpectedly took a liking to the project, seeing it as a way to broaden his appeal to the public. Bob Hoyt, friends with Eastwood through his secretary at his production company Malpaso – Judy Hoyt – thought it showed promise. He managed to convince Warner Brothers to buy it.

The entire industry wondered what he was doing when he signed on for the role. Most of Eastwood’s production team and his agents thought it was ill-advised and advised him not to make it.

The joke was on them. The movie was torn apart by critics, but audiences loved it. The New York Times called the film:

“…the slackest and most harebrained of Mr. Eastwood’s recent movies. It’s overlong and virtually uneventful, even though there are half a dozen cute characters and woolly subplots competing for the viewer’s attentions.”

Meanwhile, Variety commented:

“This film is so awful it’s almost as if Eastwood is using it to find out how far he can go – how bad a film he can associate himself with.”

Defying these reviews, it was a huge success at the box office. Both this movie and its sequel Any Which Way You Can are still two of the highest-grossing Eastwood films. When adjusted for inflation, Every Which Way But Loose ranks as one of the top 250 highest-grossing films of all time.

Produced by Robert Daley and directed by James Fargo. Eastwood plays Philo Beddoe, a trucker and bare-knuckle brawler roaming the American West in search of a lost love. He is joined by his brother and manager, Orville, and his pet orangutan Clyde. Later in the adventure they are joined by Beverly D’Angelo as Echo, who becomes Orville’s girlfriend.

While on their road trip, Philo manages to annoy everyone from a pair of police officers to an entire motorcycle gang, and they pursue him from California to Denver as he tries to reunite with Lynn Halsey-Taylor, an aspiring country music singer he meets at the Palomino Club, a local honky-tonk.

This was a classic movie from my early youth. Now, having revisited it for the first time in about 30 years, I struggle to understand why. The whole movie is a very strange beast. Neither funny enough to be a comedy, or thrilling enough to be an action movie, it doesn’t so much straddle genres as fall into a chasm between them.

It also seems like it wants to lapse into slapstick in places, but is not technically adept enough to manage it, so it just looks cheap and clumsy.

I mentioned Smokey And The Bandit above. That movie would be similarly weak as it is, after all, hung around a similarly flimsy plot. Smokey And The Bandit is then elevated across the board by the charm of Burt Reynolds, an adorable turn from Sally Field, the joy of Jerry Reed, and the sheer unbridled genius that is Jackie Gleason ad-libbing his way through the proceedings, playing perfectly off Mike Henry’s dim-witted turn as his son.

Eastwood doesn’t have the charm of Reynolds in this role, and Geoffrey Lewis is no Jerry Reed. Another big issue is the object of Philo’s desire. Sondra Lock was in a relationship with Clint Eastwood at the time this movie was made. She plays the female lead, the woman that Philo pursues across the country. She isn’t appealing enough to make you genuinely believe that Philo would take off on a quest for her.

The character is also a truly terrible human being, and it makes Eastwood’s character appear as something of a bewitched dolt.

The twin antagonists of a couple of cops with their pride damaged, and a motorcycle gang, are played for laughs but never raise much more than a sensible chuckle. This leaves them strangely ineffective and unthreatening.

The one hook in Every Which Way But Loose, one that was much-loved by me and my young peers many years ago, was the orangutan Clyde as comic relief. Through adult and critical eyes, these scenes now seem clumsily inserted, clearly filmed in isolation from the main action, and with questionable takes due to the low attention span of an animal performer.

The whole movie also suffers from that late 1970s American aesthetic of terrible architecture, even worse cars, and a pervasive feeling of cheapness and decay. The whole thing just feels unappealing. Overall, I was left thinking that Every Which Way But Loose was something from my youth that was probably best left there.

That said, I still return to the question I asked myself at the beginning of this review. Just where are the modern movies that celebrate Americana without shame? It feels like a big miss and a potentially huge gap in the market right now.

Check back every day for movie news and reviews at the Last Movie Outpost

The post Retro Review: EVERY WHICH WAY BUT LOOSE appeared first on Last Movie Outpost.