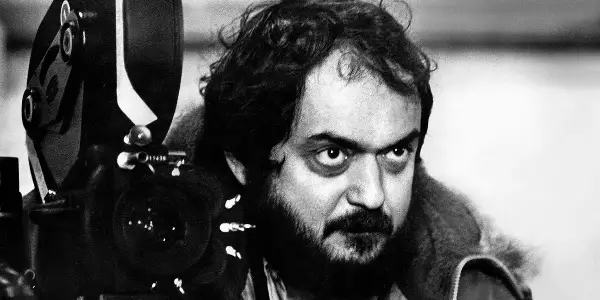

Who was Stanley Kubrick?

A recluse. A hoarder. A family man. A boy wonder photographer. A poet of violence. An unyielding, if not oblivious, perfectionist. And perhaps the most celebrated, written-about, and over-analyzed movie director in the history of the medium, particularly in light of his relatively modest output of 13 feature films before his death, at the age of 70, in 1999.

Adding to the wealth (or glut, depending on your perspective) of Kubrick material is Gregory Monro’s fine documentary Kubrick by Kubrick, which started appearing on the festival circuit in 2020 before being released on digital video in 2023. Incorporating, for this kind of essay film, the usual combination of archival stills, feature footage, and testimonies from family, friends, and collaborators, Kubrick by Kubrick distinguishes itself largely on its incorporation of seldom-heard audio recordings of interviews that the otherwise publicity-averse Kubrick did with French film critic Michael Ciment over the course of some 10 years.

Are Kubrick’s comments on his life and work revelatory? Not really. Are they interesting and at least occasionally illuminating? Sure. Are they reason enough to see this 61-minute film? Yes – especially if you are one of the legions of cinephiles who study his films as ciphers of elusive but profound and inexhaustible meaning.

For this last (and large) group, Kubrick’s thoughtful but relaxed candor will only certify his genius. Whether explaining the famously fortuitous accident of casting technical advisor R. Lee Ermey as the marine drill sergeant in Full Metal Jacket or what he sees as the impossibility of taking Alex, the ultraviolent protagonist of A Clockwork Orange, as a hero to be admired, Kubrick consistently sounds in total control of the curios, conundrums, and enigmas that his films endlessly tantalize viewers and scholars with.

In His Own Words

Not that he solves or settles them in any simple way. When speaking, for example, about 2001: A Space Odyssey and the dangers of hyper-intelligent computers that might turn hostile to humans, Kubrick rejects such fears. As he puts it, intelligence is a good thing, which means we can never have too much of it, even if it takes the form of a machine like HAL, a computer that seems to develop a will and malignant identity of its own.

And speaking of war and violence, Kubrick notes the horrors of authoritarian structures that sparked massive resistance particularly during the Vietnam War (which he depicts with such haunting aplomb in Full Metal Jacket), but he doesn’t think the answer to such conflicts is either the suppression of protest or the abolition of authority. For Kubrick, the main lesson of Vietnam was that the U. S. would probably never again enter a war that it couldn’t clearly win – a remark that seems, in retrospect, both insightful and naïve.

source: Level 33 Entertainment

It is certainly instructive to hear the director of Dr. Strangelove, Spartacus, and The Shining offer such comments in his own calm voice. Kubrick’s work has taken on such gigantic stature in film studies that it’s useful to be reminded of the thoughtful but not particularly revolutionary human being who lurks beneath the “genius” label.

The weight of that reputation bears down on any viewing of a Kubrick film, making it a challenge to offer anything like a simple critical response. He’s one of those litmus test directors: if you don’t acknowledge the inscrutable brilliance of his screen offerings, there must be something wrong, something not fully discerning, about you as a student of the medium. Not surprisingly, Monro’s film passes the litmus test pretty easily, honoring its subject in a variety of ways.

Productive Parasitism

All of which, I would suggest, makes the best reason to see this film not its fundamentally flattering view of a director already awash in adulation, but, rather, its version of productive parasitism, the documentarian creating art of his own from the work of his subject.

Most suggestively, Monro makes terrific use of a scaled-down recreation of the famous bedroom that appears at the end of 2001. In the documentary, it quickly comes to serve as a clever metaphor for Kubrick’s mind, a closed, windowless space where posters and props of the movies appear at timely moments, often revealed by a weightless, gliding camera reminiscent of Kubrick’s own mobile framing.

source: Level 33 Entertainment

Monro is particularly good at cutting from scenes of Kubrick’s films back to the bedroom replica at key moments, timing the transitions beautifully to leave questions hanging in the viewer’s mind.

One of my favorite cuts shifts abruptly from the firing squad scene in Paths of Glory, in which three condemned soldiers are tied to wooden posts captured in a careful POV shot (the rifle barrels of the executioners forming a frame within a frame), to a dramatic track-back shot – as if the camera had suddenly been caught in a vacuum – of the same firing squad posts set up in the bedroom model, sans the condemned soldiers but still backed by the sandbags piled high to absorb errant bullets.

It’s a low-angle shot in which the expanse of the all-white ceiling occupies almost half of the frame, a heavy blankness hanging over the emblems of decorously brute violence, the classical sculptures and cultured 18th-century European paintings that supply the wall sconces serving as ironic context. (Much as Kubrick himself framed a palatial 18th-century mansion high in the backdrop of the firing squad for the condemned to see just before they are shot.)

source: Level 33 Entertainment

Taking such cues from Kubrick, Monro too envisages art, culture, and civilization as not the opposites of violence, but, instead, very much a part of it – if not a cause.

Grace Notes

The documentary’s use of the iconic bedroom is filled with such subtle grace notes. One movie poster dissolves to nothing, revealing the blank white wall beneath, as the camera glides by; in other scenes, commentators and collaborators appear on a vintage 1960s television set to explain their perspectives on Kubrick’s work.

The famously intricate carpet pattern that young Danny Torrance rides his Big Wheel over in the Overlook Hotel in The Shining is transformed into a red carpet of dubious welcome in the miniature, seen in an overhead tracking shot bifurcating the bedroom as Kubrick explains how the original Stephen King novel makes it possible to read everything that happens as a product of protagonist Jack Torrance’s diseased imagination.

Monro cuts on that last word, “imagination,” to a low-angle archival shot of the hotel in a snowstorm, a daytime image benign enough in itself, but one that, in Monro’s treatment, easily becomes the stuff of nightmares, with much of the screen whited out and the building appearing ghostly, almost intangible.

source: Level 33 Entertainment

With touches like these, Monro’s documentary embraces the derivative nature of this kind of film, acknowledging that it offers us his “Kubrick” much more than it ever could the intensely private subject himself, even when he’s allowed to speak in his own voice.

The Artistic “I”

An object lesson in the vast amounts of space that Kubrick’s films allow for other imaginations to roam and create, Kubrick by Kubrick may stand on the shoulders of a movie giant, but it does so on its own two feet, the parasite distinguishing itself even as it praises its host. In the process, it adds its own set of philosophical questions about the nature of art to those that Kubrick’s films pose.

And to ones that Kubrick’s contemporaries and collaborators liked to entertain. Vladimir Nabokov, whose notorious novel Lolita Kubrick adapted (rather freely) for the screen, was himself a great comedian of artistic appropriation, the enduring paradox (as one might put it) of the artistic “I.”

In his 1962 novel, Pale Fire, Nabokov writes of the inspiring gift of another’s art, “I found myself enriched with an indescribable amazement as if informed that fireflies were making decodable signals on behalf of stranded spirits, or that a bat was writing a legible tale of torture in the bruised and branded sky.” Are such messages all in the eye of the beholder? Does their characterization as such serve merely as evidence of a deranged mind?

For Monro, decoding Kubrick’s films with the director’s own words serves as an excellent chance to write his own artful tale, however familiar its features, onto the silver screen, and to invite viewers to recognize the face of the famous director drawn in Monro’s sure hand.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.