This past week saw the release of The Book of Clarence, a movie about a down-on-his-luck guy who hits upon a get-rich-quick scheme that leads him into a heap of trouble. It’s a classic topic for a movie, but it is treading on more controversial ground than usual. Because in the case of this story about a hustler getting in over his head, the hustle happens to be set around Israel and Palestine during the life and times of Jesus of Nazareth. In fact, that is Clarence’s whole scheme: He sees Jesus and decides to get into the messiah business.

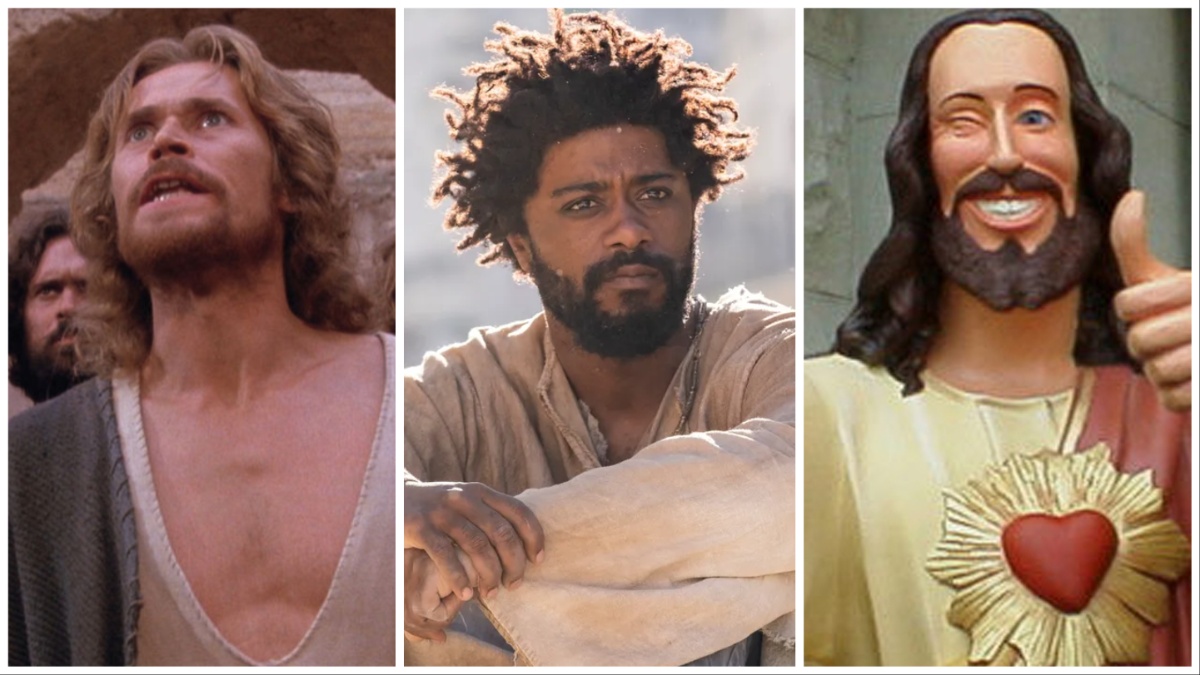

This is not the first film to portray the story of one of Jesus’ fictional contemporaries. Monty Python’s Life of Brian attracted protests, controversy, and endless talk show guest slots over its portrayal of a man who was definitely not the messiah, just a very naughty boy. Interestingly, The Book of Clarence has failed to attract anything like that level of ire so far in 2024, Anno Domini—with the obvious exception of the most perpetually ire-filled people on Earth, racists who are epileptic that The Book of Clarence’s Jesus is Black. But once you discount those, and the people who just get angry at the thought of a joke being told within 12 feet of the Bible, the way these films interact with the characters, themes, and ideas of the New Testament become a lot more interesting. Certainly more so than many more straightforward “faith-based” movies.

Not My Messiah

The first thing to note about these films is that when it comes to portraying Jesus Christ himself, there is no denying that reverence is paid. In Life of Brian, we see Christ in exactly two scenes—a nativity and a reenactment of the Sermon on the Mount that, if we ignore Michael Palin and Eric Idle squabbling at the back, wouldn’t seem out of place in the less controversial 1965 biblical epic, The Greatest Story Ever Told. The rest of the movie follows the less holy and more hapless adventures of Brian (Graham Chapman).

Likewise (again, ignoring the racists), the Jesus of Nazareth in The Book of Clarence is unlikely to upset your vicar or Sunday School teacher. Jesus seldom speaks, his face is mostly unseen (often because there is blinding sunlight directly behind it), and he really does perform the occasional miracle, such as stopping a bunch of thrown stones in mid-air, Neo style, as well as something more emotionally profound near the end. Generally, this is a reverent portrayal designed to frame the more irreverent and human story of Clarence.

Still, both Brian and Clarence contain a subversive idea, intentionally or not. Shakespearean plays showed that once you put a paper crown on a random guy and had everyone bow to him, there wasn’t, practically, much difference between them and an actual monarch. In the same way, Clarence and Brian ask us to tell the difference between the anointed Son of God, a con man on the make, and an unlucky guy who a desperate crowd has simply decided to call the messiah.

Brian never tells us the difference—we do not know if the person delivering the Sermon on the Mount is the Son of God or just a man with some politically dangerous ideas about being nice to each other (“that’ll do it,” as Crowley says at the otherwise similarly respectful crucifixion in Good Omens’ second season). Clarence, meanwhile, reveals their Jesus can actually perform miracles. But in both cases, as with most stories of Jesus in fact, the narrative is less interested in the character of Jesus himself than it is in the effect he and his teachings have on everyone else.

Their Own Personal Jesus

To understand the effect of Jesus and his teachings, however, it may even be necessary to be a bit irreverent. Kevin Smith’s Dogma is another such famously irreverent film, but one that is unmistakably Catholic in its outlook. From the outset, the movie makes clear that God is real, as are angels, demons, Jesus Christ (not seen on screen this time but still Black by the way), and the concepts of Heaven, hell, and plenary indulgence.

It uses jokes about shit demons and angels having no genitals to talk about faith, belief, and the purpose of the church. When God Herself does appear (played by Alanis Morissette, because what if God was one of us, right?), her portrayal might appear less reverent, what with her doing handstands and tweaking people’s noses, but we still do not hear God actually speak.

Supposedly this is because Her voice would blow our brains out of our ears, but it also seems to come out of a reluctance to put words in God’s mouth. Similarly, Good Omens, the Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman-authored book (as well as both seasons of the TV show) have shown us virtually every level of the celestial bureaucracy except the top one. The big G must at all times remain “ineffable.” The TV adaptation of Gaiman’s other meditation on faith, American Gods, likewise featured an absolute Jesus-verse. By the logic of the series, gods are created by the belief humans put into them—humans have put belief in a lot of different versions of Jesus. To quote the show’s Mr. Wednesday, they have “White, Jesuit-style Jesus, your Black African Jesus, your Mexican Jesus, and your swarthy Greek Jesus” to name but a few. One Jesus bleeds jelly beans from his stigmata. Another is still a baby.

Yet again though, all of these Jesuses are oddly reticent to speak for themselves. When Shadow, our protagonist, gets a one-on-one with a Jesus, the most gets is some vagaries about “belief.”

Maybe all of the above is out of the writers’ collective desire to avoid hubris. You cannot get much closer to playing God than actually writing His dialogue, but also because closing that authorial distance has provoked impassioned responses historically.

Jesus, He Knows Me

The only film to potentially match Life of Brian for outrage is Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. In it we see Willem Dafoe as my personal favorite cinematic Jesus. Despite the disclaimer at the start that “this film is not based on the Gospels, but upon the fictional exploration of the eternal spiritual conflict,” much of the film is a fairly straightforward portrayal of the events of those Gospels. The focus is different to what you might typically see—“I didn’t come here to bring peace. I came to bring a sword” is from the Bible (Matthew 10:34), but it’s not one of his most quoted lines.

But at the same time, we are not watching Jesus from the back of the crowd while on the Mount. We are right up close with him. We see him struggle and doubt. We see arguments between him and his disciples over how best to resist Roman occupation. Where it differs from other stories of Jesus’ life is that these characters don’t feel like they are acting out a story that has been told for the last 2,000-odd years. Nobody feels like they know how the story is going to turn out.

But what really pissed people off was what happened during the crucifixion. Dafoe’s Jesus is offered the out that he famously pleaded for in the Garden of Gethsemane. He is taken down from the cross in secret, he goes and marries Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey), and takes another wife when she dies. He has children and he grows old.

Ironically, given he has become journalists’ go-to guy for anti-superhero quotes, Martin Scorsese takes a leaf straight out of the comic book movie playbook here—the hero forsakes their powers and their duty to live the ordinary life they always wanted. It’s Superman II; it’s Spider-Man 2; it’s Doctor Who’s “Human Nature.” And it ends the way these stories always end: with the hero sacrificing the ordinary life they always wanted to save others.

Despite the protests and outrage at the time of its release, this portrayal of Jesus might be irreverent, but it is not disrespectful. It is an investigation of what the Jesus of the Bible is: someone who is God but is also completely human, someone who feels love for all mankind, but as a human has a complete set of needs, fears, and weaknesses.

To show why it’s necessary, one need only look at a Jesus movie that was considered controversial for entirely different reasons. The Passion of the Christ was condemned for antisemitism, as well as the abundance of graphic gore and violence it displays in its portrayal of Jesus’ last hours. But the Jesus of this film, portrayed by Jim Caviezel, is not someone we can get close to. The film’s few attempts at showing Jesus’ humanity (he invents the dining table!) are awkward and stiff, and for the rest of the film, he is less our loving savior than he is the Jesus of every terrifying crucifix sculpture you ever saw in your childhood.

To look at the subject from another perspective, Life of Brian and The Book of Clarence are not the only films to star a background character in the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Both films take a lot of notes in their portrayal of Jesus from the classic Charlton Heston movie, Ben-Hur. Like Life of Brian, that 1959 movie starts with the Nativity, goes on to show us the chatter at the back of the crowd during the Sermon on the Mount, and eventually takes us to the crucifixion.

Like Judas in The Last Temptation of Christ, Heston’s Judah Ben-Hur is less interested in Jesus’s spiritual message than the opportunity for a more direct resistance against Roman occupation. And as in Brian and Clarence, Jesus speaks little, his face is obscured—once again we know him mainly from the reactions of those around him. But this veil over the character of Jesus is not as jarring with the tone of the film as a whole, which is that of a somber historical epic.

The jarring shift in tone these other films introduce, between the serious and somber biblical retelling, and people’s more profane and material concerns of ordinary people, illuminates the Jesus story by contrasting it with more daily (or even operatic) human concerns.

Whatever your religious beliefs, Jesus, the character as portrayed in the Gospels, was emotional, argumentative, and not afraid of upsetting powerful people. He is also, frankly, funny—saying that you should pay taxes to Caesar because the money has his face on it remains one of the best bits of sly shade-throwing in theology. The Jesus of the Bible is a rich, complex and compelling character—not a blank slate to project onto.

He is a character to be engaged with, not silently watched from a distance, and you can’t do that without risking being a little blasphemous.

The post Blasphemous Movies Understand Jesus Christ Better Than Most appeared first on Den of Geek.