The Jerry Springer Show, which aired in syndication from 1991 through 2018, sometimes feels like a Rosetta Stone for understanding the modern entertainment landscape. The controversial talk show hosted by Jerry Springer wasn’t the first TV property to indulge in exploitation and it certainly won’t be the last. But even to this day it stands out as one of the grossest cultural spectacles ever broadcast, filled with paternity battles, exposed genitalia, and deviant behavior – all the while a studio audience chants “Jer-ry! Jer-ry! Jer-ry!” in a Bacchanalian haze.

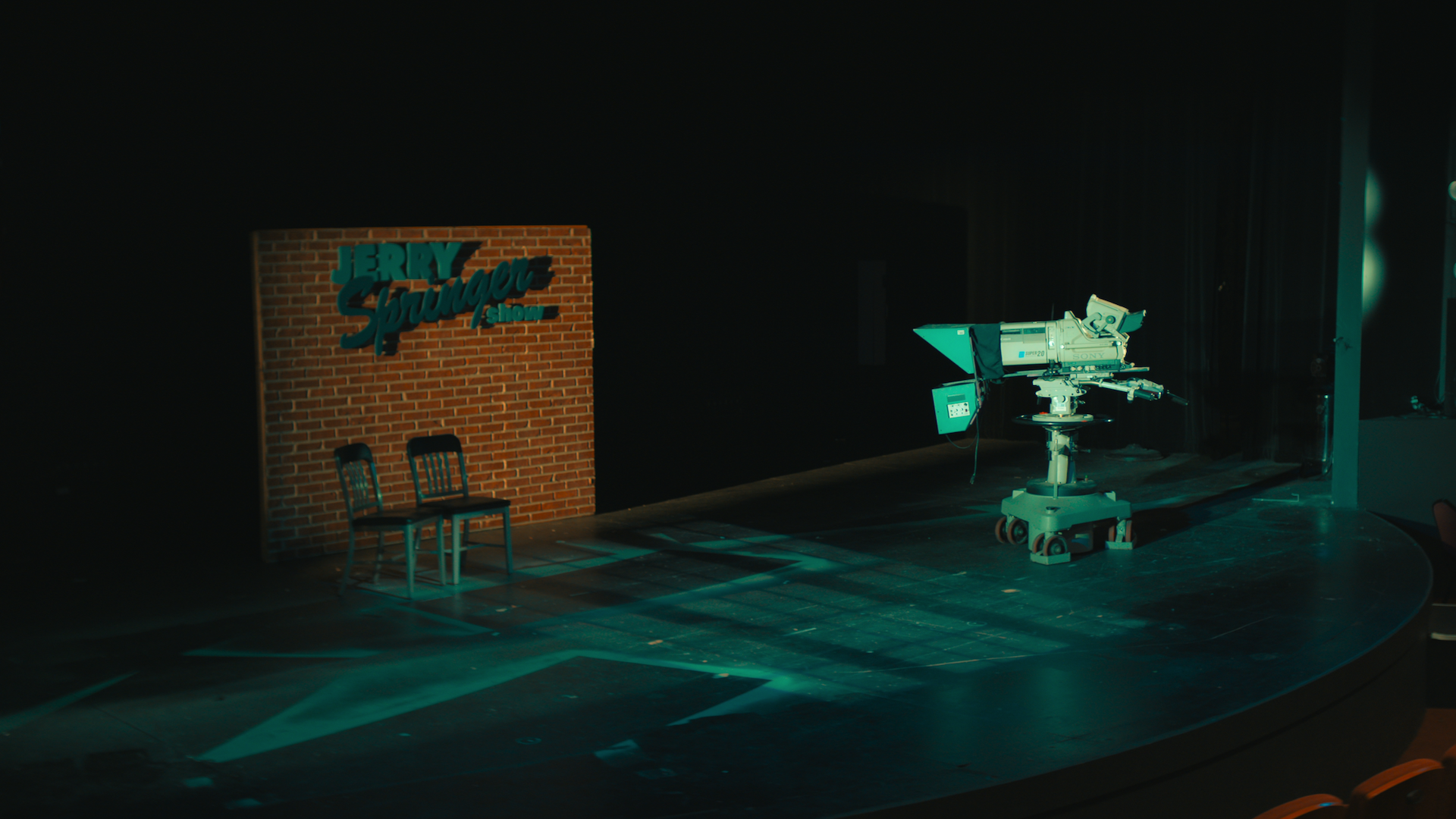

Directed by Luke Sewell, Netflix docuseries Jerry Springer: Fights, Camera, Action does a commendable job of highlighting all of the wild nonsense that Springer and executive producer Richard Dominick pulled off and how they paved the way for a golden era of Trashy TV (and Trashy Everything Else for that matter). Featuring behind-the-scenes interviews with The Jerry Springer Show writers, producers, and guests (though often more accurately “victims”), the two-part Netflix docuseries covers its rise from a tabloid wannabe to legitimate competitor to The Oprah Winfrey Show. It also includes in-depth looks at some of the program’s “greatest hits” such as the hallmark “I Married a Horse” episode and a tragic show-inspired murder.

Through it all, however, there’s one aspect of The Jerry Springer Show that Fights, Camera, Action can’t quite fully capture: Jerry Springer himself.

Springer, who died in 2023, was hardly an enigma. Having appeared in nearly 4,000 episodes of television for more than 26 years, Springer was about as public as a public figure could ever be. And that’s not even to mention his time as a politician, broadcast reporter, and frequent talk show guest (where he would routinely apologize for his role in bringing The Jerry Springer Show to the world…while continuing to host The Jerry Springer Show).

Still, for all of his overwhelming availability and showmanship, Jerry Springer was a tough nut to crack in some ways. Even amid the chaos of fist fights, incest intimations, and erotic equestrianism, Springer maintained a certain level of gravitas. As Fights, Camera, Action recounts, Springer was even adamant about making sure that everything on his talk show was “real,” and never scripted. In exerting some of his vestigial journalistic ethics over world’s worst TV show, it was almost as though he was insisting “it’s the world that’s this stupid, not me.”

As we’ve come to find out about many public figures of late, it’s impossible to produce something truly terrible without being at least a little bit interesting. And Jerry Springer was a profoundly interesting man. To fully understand why, one needs to look into his life before The Jerry Springer Show when he was a rising politician. Fights, Camera, Action does make brief mention of Springer’s time as mayor of Cincinnati, Ohio but it doesn’t quite give it the full context it deserves.

Jerry Springer wasn’t just a politician, you see, he was an incredible politician – both in the sense of being a charismatic swamp creature and a legitimately helpful public servant. The best recounting of Springer’s transition from politician to carnival barker comes from public radio program and podcast This American Life. In the 2004 episode “Leaving the Fold” (since lightly updated in a re-run after Springer’s death in 2023), host Ira Glass and journalist Alex Blumberg delve into Springer’s uniquely American political life.

Born in 1944 to Jewish refugees escaping the Holocaust, Springer was raised in Queens, New York before moving to the Midwest to get educated at Northwestern University School of Law in Chicago and eventually entering into politics to work on Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign. Following Kennedy’s assassination, Springer settled in Cincinnati, Ohio where he worked at the Frost Brown Todd (then Frost & Jacobs) law firm and began his electoral career in 1970 by running for the United States House of Representatives. Springer lost that race but tremendously over-performed expectations, pulling in 45% of the vote as a Democrat in a traditionally Republican district.

Springer would go on to get elected to Cincinnati city council three times, even after becoming immeshed in a scandal during his second term in which he used a personal check to pay for a sex worker’s services. Despite that very Jerry Springer Show-esque moment hanging over his head, he won re-election and eventually served as the council-appointed mayor of Cincinnati, being the most popular and electorally-successful member of the council at that point. The political insiders from this era speak of Springer’s prowess in shockingly reverent terms.

Democratic strategist Mike Ford told This American Life: “I worked with [Bill] Clinton [in] ’88, ’90. [In] ’92, [Michael] Dukakis. ’80, I worked for [Ted] Kennedy. ’76, I went through Birch Bayh, Mo Udall, and Jimmy Carter. [Jerry Springer] is the best I’ve ever seen, bar none.”

Cincinnati politician Jene Galvin added: “I put Springer at the level of Ronald Reagan, Bobby Kennedy, Bill Clinton. He’s that level.”

Legislative aide Tim Burke recalls witnessing Springer winning over a VFW hall to consider and respect his opposition to the Vietnam War. He also describes a time in which Springer convinced his city council peers to vote against a proposal to build the Riverfront Coliseum (now known as Heritage Bank Center) with public funds, eventually securing its construction exclusively through private funding, saving taxpayers millions of dollars.

So uh…what happened? How does a generational political talent end up pioneering the worst kind of televised entertainment? Believe it or not, it wasn’t because of the aforementioned personal-check-to-a-sex-worker scandal. Springer effortlessly moved beyond all that, even cutting a fake commercial for a local radio station advertising the benefits of using credit cards over checks. Instead, Springer’s political career ended for a much more simple reason: he lost an election.

In 1980, he stepped down as mayor to run for Governor of Ohio. After losing the Democratic primary in a close three-person race, Springer got a job as a local news anchor. From there, you can easily chart the unfortunate, if predictable path he took from likable small-time media personality to syndicated talk show host to master of ceremonies for the end of good taste. The truth is that the very same traits that made Springer a successful politician (a connection with the common man combined with a relentless drive to win) made him an equally successful, though culturally degenerative, TV man.

The most interesting part of Jerry Springer’s second life as a TV host, however, is that he vainly tried to escape it relatively early on. In 2003, amid the Bush administration’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Springer considered a run for Senate in Ohio.

“Much of the national news reported this as a joke, the talk show fool trying to dress up as a statesman,” Blumberg reports in This American Life. “But the small band of Jerry’s friends from before knew the story was actually the opposite: a former statesman was trying to shake off the costume of a talk show fool.”

Springer took the attempt seriously, speaking with Democratic organizations in universities and cities across the state. Despite the immense baggage he brought with him from The Jerry Springer Show, Springer had a knack for winning over skeptical audiences. His burgeoning campaign even put together focus groups to figure out how to address the talk show-sized elephant in the room. Their research found that, if handled properly, political messaging could get voters to see Springer as the helpful elected official he once was.

Unfortunately for Springer’s bid, the research also found that he would need to quit the show entirely to be anywhere close to electorally viable. Springer was unable to get out of his contract in time for the election and that was the end of that. In the wake of it all, Blumberg caught up with Springer for an interview in which he asked if his decade as host of The Jerry Springer Show had changed his political thinking at all.

“No, it’s just confirmed it,” Springer said. “I mean, any job I’ve ever had, it’s been the same constituency. It’s been middle and low-income people that need a voice, that need help, that need whatever. So even in my entertainment, that’s my base.”

There’s probably not a lesson to take away from all of this but there is, at least, a hypothetical to be posited. Say that Jerry Springer is able to get out of his TV contract in 2003 and goes on to win the Democratic primary for Senate. Then let’s say he’s goes on to win said election (which would be a hell of a tall order with Republican George Voinovich winning that election in real life with the highest raw vote total in Ohio history) and sticks around long enough to run for president. Say he wins that election. American voters have proven themselves to enjoy a candidate with some TV experience after all.

Is a timeline with President Jerry Springer preferable to our own? Impossible to say. The wrong president can do a lot of damage, certainly. But I’m not entirely convinced that the wrong TV host can’t do more.

Jerry Springer: Fights, Camera, Action is available to stream on Netflix now.

The post In Another Timeline, Jerry Springer Is President of the United States appeared first on Den of Geek.