Despite the singular event suggested by its title, Day of the Fight features a lower stakes match earlier in the film, hours before prizefighter “Irish” Mike Flannigan (Michael Pitt) has his title bout. Visiting the gym to check in with his trainer, Mike overhears a young fighter mocking the sparring partner he just trounced. Mike, who has spent the past several years in prison for reasons not immediately clear, is a man who’s visibly lived with shame, guilt, and the loss of his once illustrious acclaim. So the cocky contender running his mouth doesn’t object when Mike climbs into the ring. Nonetheless, and outside of the arrogant man’s opening cheap shot, Mike has total control of what transpires. He dodges each of the loud man’s blows and lands a few jabs. But before landing a knock out hook, Mike stays his hand.

“Next time have a little grace,” Irish Mike tells his opponent. “You never know who’s watching.”

On first glance, Day of the Fight has a lot in common with the great boxing pictures throughout cinema history. The black and white photography and a cameo from Joe Pesci immediately brings to mind Raging Bull. Michael Pitt plays a Mike by another name who is a sweet mook with more heart than brains, not unlike Rocky Balboa. The story of a former champ trying to clean up his life follows in the footsteps of King Vidor’s 1931 Oscar nominated, The Champ.

But where so many boxing pictures emphasize the individual spirit of the central fighter, Day of the Fight takes a more communal approach, minimizing the climactic title bout to show the many people who make Irish Mike his best self.

A Community of Combatants

Directed by Jack Huston, grandson of John Huston and former co-star with Pitt on Boardwalk Empire, Day of the Fight is unabashedly an actor’s movie. Most of the movie consists of Mike checking in on various people throughout his life, making peace with them before his title bout. Mike spends time with everyone from his supportive uncle (Steve Buscemi) to his ex-girlfriend Jessica (Nicolette Robinson), and even his abusive father (Pesci), silent while in the throes of Parkinson’s.

Each of these interactions give the actors space to deliver big monologues and chew on meaty lines. Sometimes the work plays into the actors’ established strengths. Ron Perlman barks and curses his way through the movie as Mike’s hard-driving trainer. Buscemi layers soft respect under his sarcastic lines as the uncle encourages Mike.

The best of these supporting turns comes from John Magaro, who is quickly becoming one of American cinema’s most reliable character actors. As Mike’s best friend turned priest, Patrick, Magaro makes the character at once wise enough to give guidance and relatable enough to let loose with some foul-mouthed comments. Magaro melds both tones so effortlessly that viewers may not even notice the incongruity.

Likewise, Robinson stands out as the less complex, but no less compelling Jessica. Robinson doesn’t shy away from letting Jessica’s love for Mike show, but she tampers the feelings with practical needs. Robinson takes advantages of pauses and spaces in the dialogue to let Jessica reset and ground herself, moderating the way she talks with Mike.

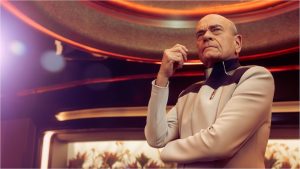

Unsurprisingly, the most notable performance comes from Pesci as Mike’s father. The film establishes Mike’s father as abusive and distant, suggesting that the kindhearted man we’ve followed throughout the movie learned about fighting from his dad. So it’s shocking to watch as Mike enters a hospital room and find his father there, looking small and vulnerable as he shakes. Pitt does all the talking as Mike, spilling his guts about his anger and frustration with the older man, but Pesci’s glances, defensive at some moments and pleading at others, unable to reach out with his trembling hand.

The train of monologues does sometimes become overbearing, making the movie feel like a series of audition clips more than believable words one person would say to another. But by the time Mike seeks absolution from another old friend, sincerity overtakes our cynicism.

The Ring of Redemption

“Sincerity” drives Day of the Fight. For as much as it builds to a match in which two people punch one another in the face, for as much as its black and white imagery and working class characters suggest gritty realism, Day of the Fight doesn’t have an ounce of cynicism. It believes whole-heartedly in the possibility of redemption and forgiveness.

Again, that sounds like familiar stuff for movies about fighters. With his pretty face atop a severe and muscular body, Pitt resembles Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler. But whereas Darren Aronofsky used Rourke’s Randy “The Ram” Robinson as a Christ metaphor, in which the main character sacrifices his body for our entertainment/sins, Day of the Fight has nothing so nihilistic in mind. Instead it’s Mike’s honesty and bravery that inspires. As such, he finds meaning in the way he relates with other people.

The connection to others is what separates Day of the Fight from most boxing films. When Huston films the fighters jabbing at the camera, or cuts away from the match to show how other people respond, he shows that it’s not all about Mike, Irish Mike against the world. It’s Irish Mike within the world, his actions reverberating through the many people who made him the person he’s become.

So when Mike fights, it’s not a man to man battle. It’s a struggle of people trying to support and forgive one another, despite sometimes disastrous mistakes. It’s a fight for grace, something so rarely found inside the boxing ring.

Day of the Fight is playing in select theaters nationwide.

The post Day of the Fight Reinvents the Boxing Movie appeared first on Den of Geek.