A man walks alone in the snow. Hours earlier on this frigid morning, local Romani took his horse and left him stranded—a cruelty or a comfort, depending how you read their warning not to seek out the desolate castle on a hill. There, he is told, awaits only shadow and demons; a nightmare without end. For anyone who has seen F.W. Murnau’s original Nosferatu from more than a century ago, as well as many of the other films that have played in Bram Stoker’s crypt, this all has the unmistakable air of familiarity.

Yet in rarefied moments, Robert Eggers’ 2024 retelling of the classic vampire story feels strangely new. And in this particular sequence, it becomes downright breathtaking as Nicholas Hoult’s fated traveler stands atop a clearing to look out at a landscape of wintry frost and gloom. The composition is a recreation of painter Casper David Friedrich’s “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” oil masterpiece; but it’s also one of countless examples of the aching beauty that the filmmaker behind The Lighthouse and The Witch has wrought from such well-worn material.

As the most aesthetically beatific rendering of the Dracula myth put to screen, Eggers’ Nosferatu is also the most perverse. Like a child who enjoys skidding across newly fallen snow to reveal the slush and mud beneath, Nosferatu ’24 relishes in its Romantic flourishes and allusions while also wallowing in the putrid and festering decay that lies at the core of its parable. It is a film which seeks to dig deep beneath the vampire’s native soil in order to find the gruesome (and yet queerly alluring) appeal that has kept the creature alive all these centuries; and in the process, it transforms a Halloween staple into a psychosexual tragedy about a young woman and her most anticipated suitor: Death.

The woman in question is named Ellen Hutter (Lily-Rose Depp in the Mina Murray role). Like other versions of this character, she is a woman graced with an otherworldly intuition for the supernatural. However, more so than any other telling, this Nosferatu is her movie. Hence the film beginning in her childhood bedroom where a troubled girl calls out for companionship in the loneliness of night… and finds a shadow return her summons by raising its taloned silhouette across her nightgown. Ever since, Ellen has been stalked by darkness, though when we come to her as an adult, she lives like a proper Victorian in 1838 Germany with doting husband Thomas (Hoult). He urges her to never speak aloud those macabre fancies which follow from her dreams.

Nonetheless, he soon finds himself living in them after he is required to sell crumbling real estate in his hometown of Wisburg to Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård), an eccentric nobleman who resides in the Carpathian Mountains. Probably the closest interpretation to the historical Vlad the Impaler we have seen in a Dracula movie, Skarsgård’s Orlok is domineering and brutish, demanding all attention despite rarely leaving the most squalid corners of his ruined castle. He quickly makes plain, too, his interest in Thomas’ wife, whose locket he steals in the night—among other things judging by the rodent-like bite marks Thomas finds on his chest each morning.

Chances are you know where this is headed, complete with buckets of rats when Orlok arrives in Ellen’s port city. He might come for Thomas’ raven-haired bride, but he won’t be satiated until all of the city is under his dominion of plague, pestilence, and despair. In this context, even Willem Dafoe’s delightfully kooky Professor Albin Eberhart Von Franz (Van Helsing by another name) seems ill-prepared to save Ellen’s friends and neighbors from the monstrous shadow descending from above.

Much in the marketing has been made about the mystery of the vampire’s appearance. In spite of the makeup Murnau used to transform actor Max Schreck into a walking cadaver in 1922 being the most iconic image of a vampire this side of Bela Lugosi, Eggers and his collaborators have elected for something slightly different. The rough build and shape of Schreck’s Orlok remains intact, but the design is more subdued and grounded (gone, too, is the problematic “Shylock nose” and in its place comes an amusingly antiquated hairstyle from medieval Transylvania). But the most striking thing about the vampire’s appearance is how entirely devoid it is of what viewers might expect from a character played by Skarsgård.

The handsome Swedish actor wholly disappears into the character, even more so than he did in his showy turn as Pennywise the Clown in It. At least with Pennywise, the dancing eyes remained. But what we are left with in Nosferatu is a corpse with sunken, blazing pupils and a booming voice of entitlement and sneering loathing for everything in his presence, save of course Ellen.

The choice to pare down the story’s focus to essentially three people—Ellen, Thomas, and the demon between them—heightens the emotional depth of feeling in this above Murnau’s original, the Werner Herzog remake, and just about every other Dracula. This is partially due to Eggers seeking a humanist grounding in all the performances, even when Dafoe is allowed a slightly longer leash once it’s time to chew scenery as the half-mad occultist. That much needed levity never tips over into excess though, like Anthony Hopkins mugging for the camera in Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula. There is a deeply empathetic concern for all the players in Eggers’ treatment.

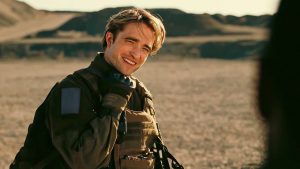

In terms of the central triangle, this is achieved in large part by Hoult—whose puppy dog eyes could make a monster like Peter III in The Great sympathetic—and Depp. Hoult provides the Jonathan Harker archetype with some romantic heft strangely lacking in every other screen version, but Depp is the true revelation as Ellen, a woman whose unhealthy draw toward the dark manifests itself in several showstopping scenes of possession and contorted frenzies that blur the line between rapture and torture.

Depp provides Nosferatu with a soul, giving texture and context to the ancient motif of “Death and the Maiden.” Whether it’s The Daemon Lover, Renaissance cuttings eulogizing the Black Death, or Twilight, the artistic appeal of youth (usually feminine) and personifications of fetid decay has lingered in our popular imagination since time immemorial. Eggers utilizes one of its most famous articulations to trace the collective, Jungian draw we might all feel toward macabre, destructive things—drawing a line between now, the story’s 19th century roots, and as far back as “heathen times” antiquity.

The appeal, then, of this Nosferatu is the juxtaposition between the radiant and the rancid. By drawing compositions from infinite shadings of inky black shadows, Eggers and frequent cinematographer Jarin Braschke craft a beautiful world that will likely be only fully visible on the big screen. Their lush Gothic palettes are further accentuated by production designer Craig Lathrop’s sets, which have a faintly Dickensian warmth in their early 19th century grandeur. Seeing those beautiful things, lit entirely by candles or gas lamps, slowly give way to the gloom, just as all the characters descend into a primal madness by film’s end, is as enticing as it is disturbing.

The contrast even seems designed to carry the viewer inside the vampire’s worldview. Unlike most movie vampires these days, Count Orlok is a genuinely sinister and evil presence that corrupts Eggers’ aesthetic and emotional earnestness with abomination. Right down to an unforgettable final shot, the creature’s desire to destroy and rot all in its presence is total. Yet like this beast, Eggers and his film find comfort, bliss even, from watching pretty things wither and die. Their final repose is what lets them live forever.

Nosferatu opens in the U.S. on Dec. 25 and in the UK on Jan. 1. Learn more about Den of Geek’s review process and why you can trust our recommendations here.

The post Nosferatu Review: Robert Eggers’ Beautiful Nightmare Made Flesh appeared first on Den of Geek.