This article contains major Gladiator II spoilers.

Ridley Scott has made a triumphant return to the arena with Gladiator II, a piece of cinema with a capital “C” that has all the spectacle you would want from a sequel to his 2000 masterpiece. But just as with the Russell Crowe-starring original, Gladiator II doesn’t simply coast on its epic military campaigns and brutal Colosseum battles. It wants to say something too.

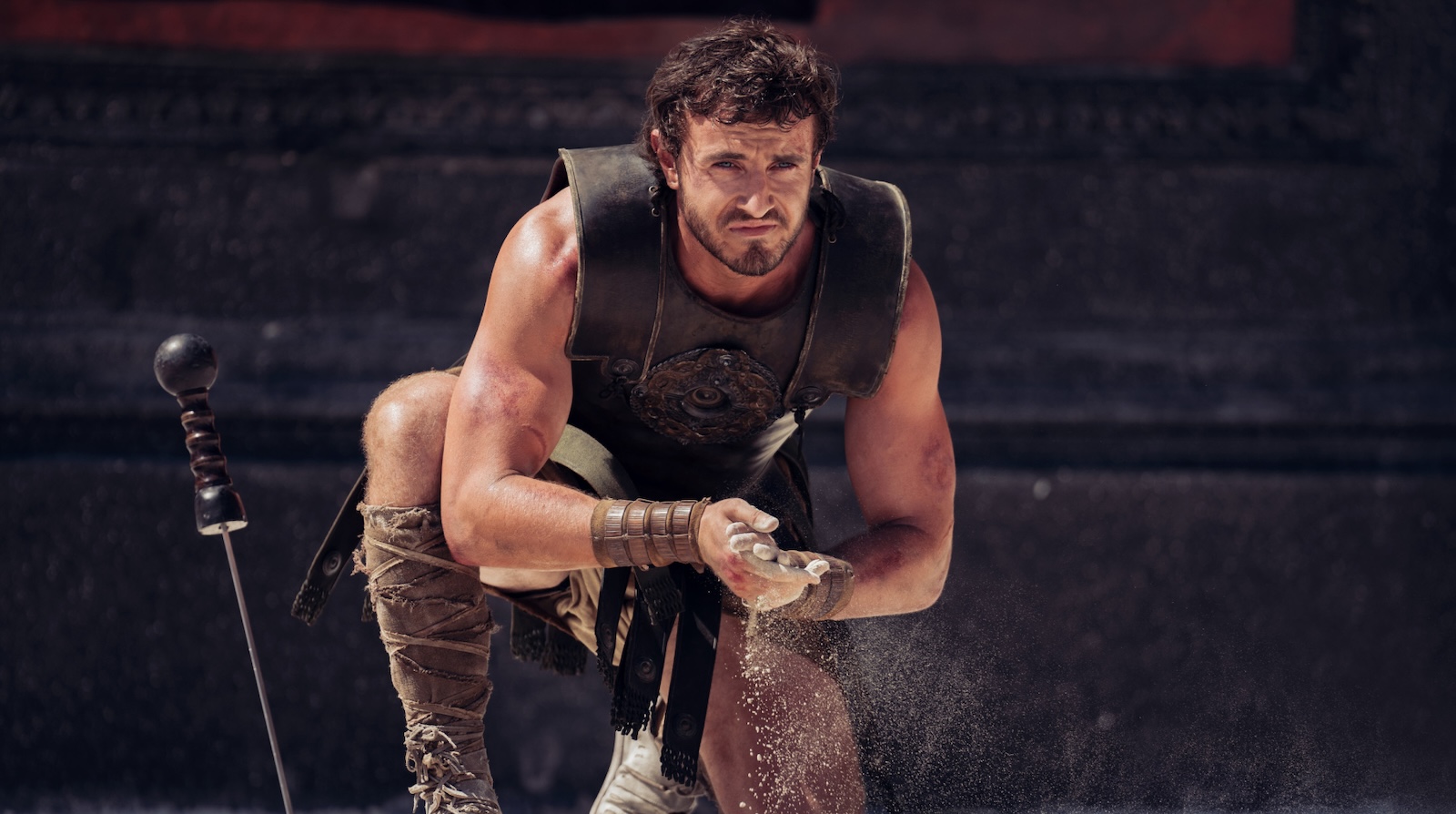

It’s also clear that Sir Ridley is a fan of the classics—a fact you might’ve picked up on in Prometheus and Alien: Covenant. And in Gladiator II, he and writer David Scarpa mine similar subtext from ancient mythology. This is introduced in a pivotal scene early on in the movie in which Lucius (Paul Mescal) is first introduced to twin emperors Geta (Joseph Quinn) and Caracalla (Fred Hechinger) as a champion-in-waiting, captured during Rome’s conquest of Numidia.

After being forced to kill a fellow gladiator in a bloody brawl, Lucius refuses to speak to an infatuated Geta, opting instead to recite a poetic verse:

The gates of hell are open night and day;

Smooth the descent, and easy is the way:

But to return, and view the cheerful skies,

In this the task and mighty labour lies.

Power-hungry gladiator wrangler Macrinus (Denzel Washington) attempts to diffuse tensions by claiming he has taught his “foreign” slave poetry, but Lucius’ outburst—be it designed to prove that he is no mere “barbarian” or to hint at his own Roman heritage—is pointed enough to intrigue all parties.

This specific Virgilian verse, which we later find out was taught to a young Lucius by his mother Lucilla (Connie Nielsen), carries much more weight to the story than a simple act of defiance, however…

The Aeneid: Virgil’s Ancient Roman Epic

As revealed in the film, the verse hails from the poet Virgil and his epic The Aeneid. The poem follows the story of the Trojan hero Aeneas, who escapes the fall of Troy and is aided by his mother, the goddess Venus. Aeneas goes on to lead his fellow survivors on a perilous journey across the seas to Italy. There, he is fated to settle and lay the groundwork for what will become Rome several generations later—but not before being reluctantly dragged into a bloody war against some none-too-welcoming locals.

Constructed between 29 and 19 B.C. and commissioned (according to some) by the first Roman Emperor Augustus, The Aeneid was designed as a kind of national epic, inspired by the grand works of the Greek poet Homer (Books 1-6 can be roughly compared to The Odyssey, and Books 7-12 to the The Iliad). It not only promoted traditional Roman virtues of family, duty, and honor, but also suggested a heroic weight to the lineage of Augustus, whose reign ushered in a period of relative peace and stability.

That means The Aeneid would have been around for over 200 years before the co-reign of Geta and Caracalla (209 to 211 A.D.), and definitely would have been established enough for Lucius to have studied it as a youngster—not that Scott’s film is super concerned about pinpoint historical accuracy (but that’s not a debate for here).

The specific verse that Lucius quotes, meanwhile, is from Book 6, in which Aeneas goes on a quest to the Underworld to visit the spirit of his father, Anchises. It is uttered by the Sibyl, a priestess who guides Aeneas on his descent, and in very basic terms means that getting down, or “dying,” is easy; it’s coming back to life that is the real struggle.

After many trials, Aeneas meets his father in the fields of Elysium and learns of his destiny to found a great city. He is, after all, introduced to the unborn souls of Rome’s future heroes.

How The Aeneid Ties Into Gladiator II’s Story

So how does this relate to Lucius’ journey? On a basic level, it speaks to our hero’s near-death experience at the beginning of the film where his vision sees him stirring on the banks of the river Styx as his wife, who has been killed in battle during the Numidian campaign, joins the ferryman Charon (also encountered by Aeneas) to journey to the afterlife. Leaving her to “return” to life is a path beset by pain, violence and, yes, “mighty labors.”

But there are other parallels between Aeneas and Lucius too. Under Geta and Caracalla’s debaucherous, tyrannical rule, the Rome of Gladiator II is in a sorry state, corrupt beyond measure and rotting from within. And Lucius, who eventually accepts his lineage as the descendant of Marcus Aurelius and a “prince of Rome,” ends up on his own quest to re-“found” the ailing city according to his grandfather’s dream of a fair and peaceful empire.

He even looks to his real father, Russell Crowe’s Maximus—notably last seen walking through a spiritual field of golden wheat and abundance—for guidance.

The Aeneid is obsessed with the concept of “pietas”—that is, a sense of duty or devotion to one’s family, country, and fate. An acceptance of obligation. A higher calling, if you will. To Virgil, Aeneas is almost the personification of this, leading his fellow Trojans to a new home despite great personal sacrifice along the way.

Likewise, Lucius has spent most of his life in exile, actively hiding from his destiny, only to grudgingly acknowledge it on his “return” to his old life. Scott himself alluded to this in an interview with Premiere, comparing the end of the film to The Godfather where a man ends up “with a job he didn’t want.”

He went on to reveal that, should there be a Gladiator III, it will find Lucius as “a man who doesn’t want to be where he is.” Expect more mighty labors ahead…

The post Gladiator 2: Why That Virgil Quote Is So Important to Lucius’ Story appeared first on Den of Geek.