Wuthering Heights (2026)

Come Undone.

Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (first published in 1847) has never been an easy novel to pin down on screen. It’s gothic romance, yes, but also a bruising story about class, cruelty, and obsession — told through layered narration and spanning generations. Filmmakers have been taking swings at it for a century, from the famous 1939 William Wyler film to later attempts that leaned harder into the book’s rawness (Andrea Arnold’s 2011 version often gets cited as one of the more “accurate” modern adaptations).

Which is why Emerald Fennell’s 2026 “Wuthering Heights” arrives with an almost mischievous honesty baked into its title: the quotation marks are a statement of intent — this is not the book, but a version. And Fennell has been upfront about the approach: compressing the story and focusing primarily on the Cathy/Heathcliff core rather than attempting the entire sprawling architecture.

I’ll be transparent: I don’t know the source material in deep, scholarly detail. But you don’t need to be a Brontë expert to feel what Fennell is doing here. This is not a fidelity-first adaptation. It’s a film that uses the novel as a launchpad — keeping the iconic relationship and mood, while rearranging character functions, smoothing out structural complexity, and reshaping the endpoint into something cleaner, more immediate, and more “cinematic.”

Stormy hearts, sharper tailoring.

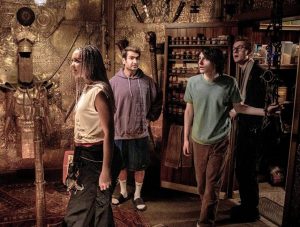

The plot plays out in broadly recognizable beats. Catherine “Cathy” Earnshaw (Margot Robbie) lives at Wuthering Heights — an isolated, windswept country estate that functions almost like a character itself, its harsh environment reflecting the emotional volatility of those who live there. Into this world arrives Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi), an orphan taken in by Catherine’s family, who quickly forms a deep, intense bond with her. Their relationship becomes co-dependent, passionate, and ultimately destructive as they move from childhood companionship into something far more complicated and emotionally charged.

Nelly Dean (Hong Chau), the household’s long-time caretaker, sits close to the center of the story as both observer and participant, watching the relationship unfold while occasionally shaping events herself. As Catherine grows older, she finds herself pulled between her connection to Heathcliff and the promise of stability and social status offered by neighboring gentleman Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif). Edgar’s sister, Isabella Linton (Alison Oliver), becomes another emotional pawn as tensions escalate, deepening the fractures between characters.

After a particularly bitter falling-out, Heathcliff disappears, only to return years later transformed — wealthy, composed, and driven by a simmering desire for revenge. His return sets off a chain reaction that targets not only the society that once rejected him, but also the people he believes abandoned or betrayed him, pushing the story toward darker emotional territory.

Revenge never looked this composed.

But the way the story is told — and what it chooses to emphasize — is where Fennell’s version most clearly splits from the classic reputation. For one, this version sidelines the novel’s broader generational structure and instead narrows the focus to the doomed romance as the main event, rather than the book’s longer echo of consequences. There are also notable character consolidations. The film appears to fold elements traditionally associated with Hindley Earnshaw into a harsher portrayal of Mr Earnshaw (Martin Clunes), shifting where much of the story’s cruelty originates and subtly altering the texture of Heathcliff’s revenge. Even the framing devices feel streamlined, with narrative elements pared back to shape the story into a more contained and cohesive cinematic structure.

Thematically, the film feels less interested in the novel as a knot of social history and narrative architecture, and more interested in the romance as a seductive, destructive force — an obsessive loop where love becomes possession and identity. Fennell pushes the material toward heightened sensuality and provocation (more explicit, more stylized), which will work for some viewers because it externalizes what older adaptations sometimes keep repressed. Where this approach can frustrate is that the story’s ugliness becomes, at times, a vibe — a gothic, erotically-charged fever dream — rather than a slowly tightening psychological trap. That may be the point, and it’s consistent with Fennell’s filmography, but it also means the emotional devastation can land as designed rather than inevitable.

Romance dialed to ‘wuthering.’

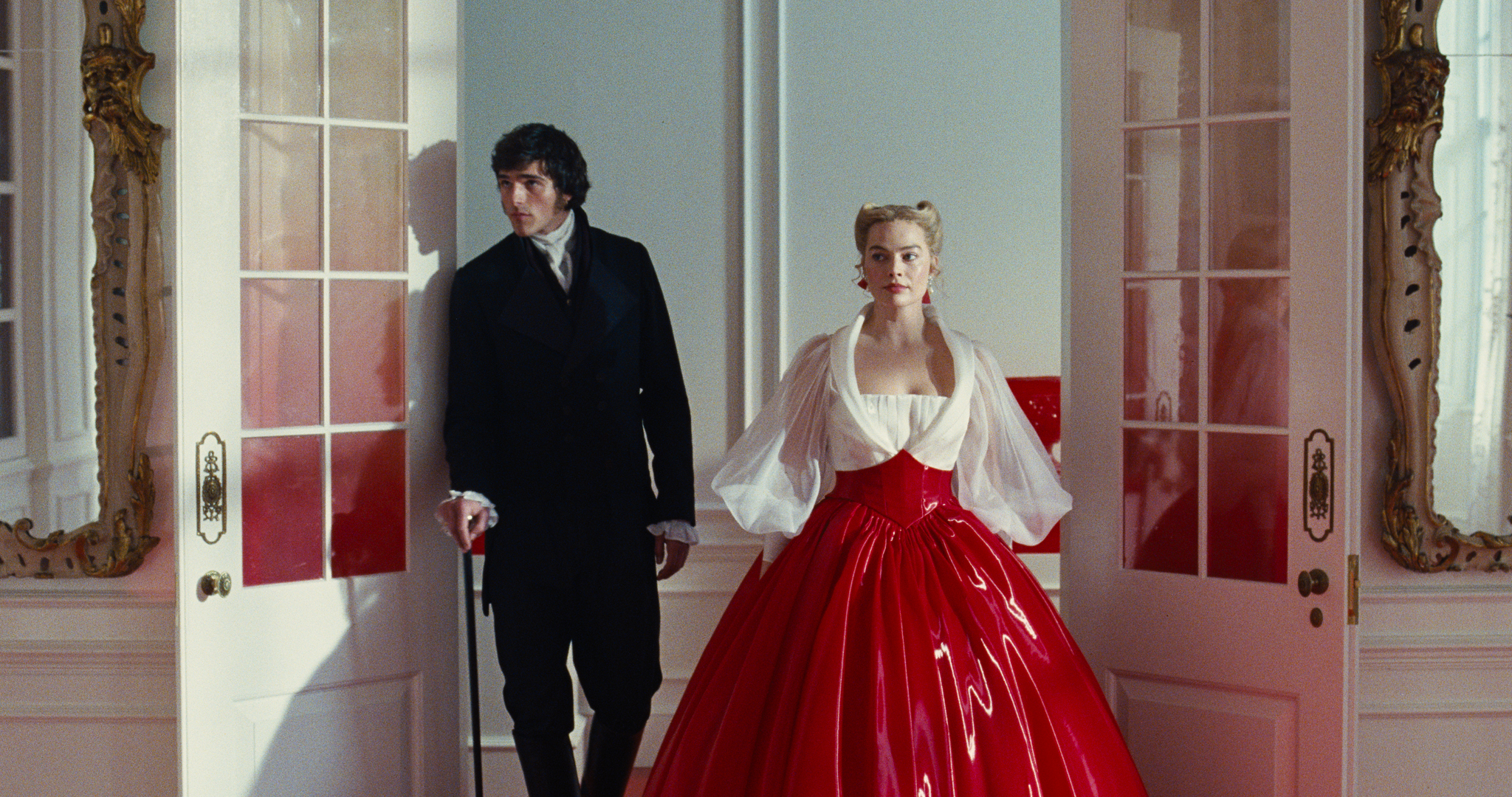

If there’s one aspect where the film excels, it’s in its visual style. This is a lush, premium-feeling period production, and the craft does an enormous amount of heavy lifting. Production designer Suzie Davies creates environments that feel emotionally expressive rather than purely historical, shaping Wuthering Heights itself into a claustrophobic, masculine space built around darker, heavier tones, while Thrushcross Grange contrasts with colder metallic finishes and refined surfaces that almost feel like a gilded prison. Costume designer Jacqueline Durran delivers another strong visual identity, blending period silhouettes with stylized, almost fantasy-driven flourishes that prioritize mood over strict historical accuracy.

Color plays a major role in defining the film’s visual language. The palette leans heavily into deep gothic hues — blacks, whites, and striking bursts of red that signal desire, violence, and emotional escalation — alongside cooler metallic tones that give interiors a reflective, almost artificial quality. This contrast between dark moorland naturalism and heightened, jewel-toned glamour reinforces the emotional divide between worlds and characters, particularly as Catherine’s visual identity evolves throughout the story. Cinematographer Linus Sandgren captures it all with a polished, big-screen sensibility, favoring rich textures and controlled compositions that emphasize these saturated tones and stylized contrasts, while Anthony Willis’ atmospheric score and Charli XCX’s contemporary soundtrack choices subtly reinforce the film’s blend of period gothic and modern emotional intensity. The result is easily the film’s clearest strength.

Performance-wise, the casting choices are clear in their intent. Robbie’s Catherine is poised and readable — sharp enough to feel dangerous while still carrying a vulnerability that leans into tragedy — while Elordi approaches Heathcliff as a romantic threat, defined by wounded pride, simmering intensity, and a physicality that modernizes the character’s appeal. Around them, Hong Chau brings a grounded presence as Nelly, often functioning as the film’s emotional anchor and occasionally delivering dry, understated moments that introduce flashes of dark humor amid the gothic intensity. Shazad Latif’s Edgar works as the credible “stable” alternative, with several quieter exchanges leaning into awkward social comedy that subtly undercuts the heightened melodrama, while Alison Oliver’s Isabella fills the narrative role required of her within the emotional conflict, occasionally pushing into exaggerated tonal beats that feel intentionally ironic rather than fully dramatic. Martin Clunes commits fully to the darker reinvention of Mr. Earnshaw, yet even here Fennell introduces moments of uncomfortable, almost morbid humor that highlight the character’s grotesque excess.

The performances ultimately rarely rise beyond “solid.” Everyone remains perfectly watchable, and no one falters in a way that distracts from the film, yet there is a lingering sense that the cast never fully elevates the material into something operatic or truly unforgettable — a quality that feels particularly important for a story built on emotional extremity and destructive passion.

Red flags — now available in widescreen.

That approach reflects the work as a whole. Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” is visually striking but clearly uninterested in positioning itself as a definitive or strictly faithful adaptation, particularly with its narrowed narrative focus and altered structural choices. The stylized, compressed, and often ‘vibes-forward’ interpretation may distance audiences seeking deeper emotional immersion. The craftsmanship and intention are evident throughout, but the overall result is an uneven reinterpretation — thoughtfully assembled and visually impressive, yet ultimately more admirable than emotionally resonant, never fully capturing the raw intensity that has allowed the story to endure.

3 / 5 – Good

Reviewed by Dan Cachia (Mr. Movie)

Wuthering Heights is distributed by Warner Bros. Australia