In the 19th century, the French had a nickname for sex that translates to “the little death.” Something about the stillness after release. Well, in Emerald Fennell’s skewed but seductive reworking of Wuthering Heights, death is loud, violent, and might best be described as the biggest, er, pleasure. It’s an aphrodisiac; a lightly seasoned fetish where morbidity and mortality entangle themselves along a fog-strewn countryside.

This is clear in the movie’s opening moments where the presumable sounds of a man’s groping excitements turn out to be his final death rattles as we see him swing from a noose into view. As he reaches his final convulsions, a titillated public gawks on, holding its breath in anticipation. In an instant, the filmmaker seems eager to acknowledge her kinship with a fella who knows how to transfix the leering crowd.

Fennell’s lurid and dramatic reimagining of Emily Brontë’s literary classic is similarly stormy, aggressive, and distracted with kink. And its biggest turn-ons would seem to be the kind of lush excesses associated with studio melodramas of yesteryear. In the press, the writer-director has name-dropped James Cameron’s Titanic as a formative influence, and it’s definitely a touchstone in this Wuthering Heights’ more maudlin moments. However, the director and her department heads seem to take much and more gratification from emulating the lushness of Golden Age Hollywood romances of the 1930s, including most vividly Gone with the Wind and its blood-red sunsets being transferred from Tara to north Yorkshire. Yet there are wider, more perverse influences too.

Never mind the crumbling old house of the film’s title, the very landscape on which this ruin sags evokes the expressionism of Weimar Germany and the earliest onscreen oddities of the literary Gothic that the Brontë sisters helped pioneer. The drooping, jagged rock faces of the English moors loom over the shabby Wuthering Heights house to the point of virtually collapsing atop the damn thing. It’s as if both hearth and land have become exhausted after centuries of overstimulation.

This is not the Victorian England in which the Brontës lived, nor the feel-good fairytale land of modern streaming service bodice-rippers, which gloss the genre over with a veneer as hot as a season’s greetings card from Hallmark. Nay, Fennell’s Wuthering Heights lives in a seething, ancient decrepit place that only existed in the movies of yore, and in its best moments she transports viewers back to the kind of sweeping spectacle that can beguile and enrapture. At one point upon “moving up” in the world, Margot Robbie’s vain and capricious Cathy Earnshaw even enters a new bedroom that literalizes the basic conceit of German Expressionism, with the walls painted by her dithering husband to resemble her freckled skin.

The sumptuous designs—derived from what must be the fevered dreams of production designer Suzie Davies, costumer Jacqueline Durran, and cinematographer Linus Sandgren—conspire, casting a spell so blinding in its orgy for the eyes that it even distracts from whatever litany of sins the movie might conceal. Which for English professors and purists of the page, will surely be legion.

This is immediately apparent after the aforementioned opening prologue at a hanging witnessed by a young, nameless boy who will one day soon be known as Heathcliff (Owen Cooper as a child, Jacob Elordi for the rest of the picture). Gone is the framing device about a ghost on the moors and a lost love. This Wuthering Heights is instead a pitch black fairytale about a boy and a girl, with only the morality of the Marquis de Sade between them. Heathcliff is a wild, feral thing, who earns his name after he is adopted (stolen, really) by a drunk and hateful man from generations of squandered wealth, Mr. Earnshaw (Martin Clunes).

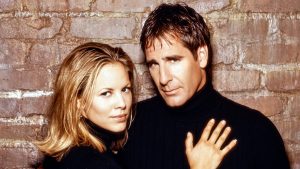

Earnshaw brings the boy home to his dying house on the moors, and to his daughter Cathy (initially Charlotte Mellington), whom he allows to name the vagrant. Young Cathy also quite visibly falls in love with the lad, despite the cruel patriarch using young Heathcliff as both a servant and glorified whipping boy. The old man even savors denying the child an education in basic reading and writing. Somehow, despite this unhappy childhood, Heathcliff grows up to be the strapping Elordi while Cathy blossoms into Margot Robbie at her most bewitching. As adults, the infatuation between Cathy and Heathcliff is inescapable to everyone. Yet they will not consummate.

Cathy is acutely, selfishly, aware of her beauty, and the effect it has on Heathcliff as well as the new neighbor, poor, clueless Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif). Mr. Linton and his young, impressionable ward Isabella (Alison Oliver) have moved into the luxurious estate across the moors, Thrushcross Grange, where every room is bedecked in crystal or pastels more perfect than the six-foot dollhouse Isabella has brought with her. In short order, Cathy has a marriage proposal from the kind but diffident wealthy man, and a choice to make between the desires of her heart—and flesh—which lean toward the dark, brooding silhouette of Elordi’s six-and-a-half foot frame, and Edgar’s comforts. Yet it is what occurs after she errs, causing Heathcliff to abandon the range for five years before returning as a man of mysterious wealth, where the real duplicities and depravity begin.

Fennell’s Wuthering Heights is less an adaptation of the novel than it is a lascivious daydream of what every young, repressed non-reader imagines when staring up at its stylized title on a dorm room wall, or while listening to the spooky synths of Kate Bush crooning about running along ‘em moors. It is Fifty Shades of Technicolor Rouge, wherein each fetid desire, and implicit moral corruption that’s simply suggested on the page, is made achingly, swooningly vivid in a movie that jettisons the multigenerational degradation and even supernatural underpinnings of the book in favor of an epically bad romance.

The thing has as much concern with literary fidelity as Cathy or Heathcliff do for their eventual spouses. Its sense of historical verisimilitude is also proudly abandoned for wondrous postmodern costumes with plunging necklines and 1980s music video accoutrements that suggest this has a better chance of existing in the same world as Coppola’s equally indulgent Dracula as it does our own.

The thing is that, for the most part, these liberties work. At its best moments, Wuthering Heights is a thunderclap of lurid melodrama flashing across the gloom of night!

It has indeed been decades since a major Hollywood studio has produced a populist and overwhelmingly romantic fantasy like this. As a Millennial, Fennell grew up with many of the aforementioned touchstones from the ‘90s and she succeeds in echoing their transportive qualities via the florid escapism of rainy rendezvouses and snapped corsets.

There has been plenty of chatter before release about Elordi’s casting in the film and whether he matches the ambiguous complexion described in the book as having a “dark” and “gypsy” like affectation. However, the choice of the looming Australian proves to be Fennell’s masterstroke. He brings a rugged dynamism to Heathcliff (he’s also the only member of the ensemble who bothers attempting a Yorkshire accent). Even the way he smokes his pipe while surveying Cathy’s pampered married life with smiling contempt burns to the touch.

When matched with a Robbie who’s willing to lean into every inch of her ethereal beauty, and in a role where she need not pretend to be oblivious of its effect, the chemistry begs to come with a warning label about handling with fire-repellent gloves. Fennell might shamelessly borrow from Selznick and Curtiz with grandiose shots of Heathcliff and Cathy on the moors, but when Elordi lifts the foot-shorter Robbie up to meet him by her corset, the crackle is all-consuming.

Even so, I suspect the relationship that will provoke the most discourse after release is not Heathcliff and Cathy’s, but what occurs when a vengeful other man decides to set his sights on Oliver’s poor, hapless Isabella. Heathcliff’s loveless seduction of an innocent was always among his greatest cruelties of the novel, but in this film it takes on perverse dimensions, particularly with Oliver playing the younger Linton with the pent up lust of a tumblr fangirl who spends her days reading Wuthering Heights fan fiction. Which is to say, she might embody much of the film and novel’s modern target audience, making the depravities of our Byronic womanizer take on a loaded context that transgresses lines you’re not entirely sure the movie is aware exists.

In fact, the film’s entire footsying with slash-fiction fancies while maintaining the dark malice at the core of Heathcliff and Cathy’s shared souls is where the picture runs into its biggest hurdles. Wuthering Heights ’26 approaches the end of its story with the conventionality of a standard BBC melodrama. But the thing about the Wuthering Heights is Cathy and Heathcliff are the worst, which makes their doomed dalliances pitiful but hardly aspirational. Yet 11th hour attempts to paint this with a Jack-and-Rose brush onscreen seem sudden, unearned, and smear the picture Fennell had so meticulously composed moments earlier. The final minutes of the movie, in fact, peter out when they should be crescendoing.

Despite warping and drastically reducing the scope of the story, it still feels too vast and unwieldy for Fennell to firmly get her arms around. That probably won’t matter though to most audiences, including ultimately myself. The filmmaker has such command of the tone and vibe she seeks that it is easy to become drunk on the sheer beauty of her and Sandgren’s cavernous compositions in the dilapidated ruins of Wuthering Heights’ carriage house. Sunlight steals through a hundred cracks in the ceiling, creating an unlikely halo around Heathcliff and Cathy, even in moments of exquisite damnation.

It’s not Brontë, and will likely be reviled in literature classrooms for generations to come. Still, one imagines the students will nevertheless swoon, or smirk, while partaking in this most decadent of infidelities.

Wuthering Heights opens in theaters everywhere Friday, Feb. 13.

The post Wuthering Heights Review: Bastardization of Brontë Still Makes for Bodice-Ripping Delight appeared first on Den of Geek.