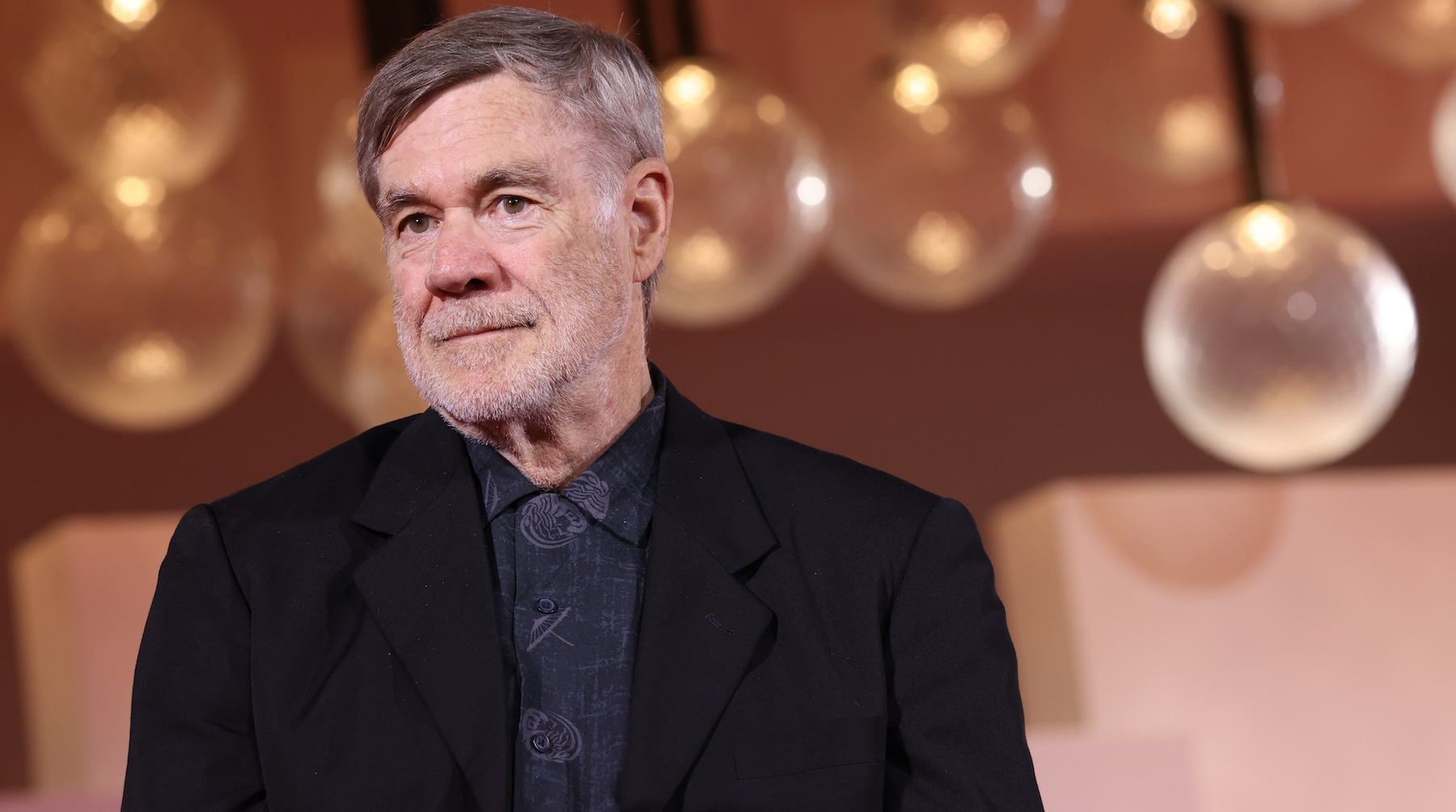

Gus Van Sant has always been drawn to stories seeped in truth and reality, even when he’s making fiction. One of the defining voices of independent cinema over the last 40 years, beginning with breakout work in movies like Drugstore Cowboy and My Favorite Idaho, the filmmaker has essayed everyone from gay rights activist Harvey Milk in the Oscar-winning Milk to, perhaps more daringly, a thinly fictionalized account of the then novel phenomenon of school shooters via the 2003 Palme d’Or winner, Elephant. Yet whether true stories or ostensible Cinderella yarns about a couple of buddies from Southie ready to show the world these apples, it is an underlying authenticity which Van Sant insists makes his films sing.

“You want to stick to the original realities, because usually they are more intense and more dramatic than fiction,” Van Sant tells us over a Zoom call from his West Coast home. “I’ve done a lot of stories that are coming from reality, like almost all of them. Maybe Even Cowgirls Get the Blues was completely devoid of reality, but almost every other script had real characters that were being drawn from, including Good Will Hunting.”

Van Sant points to his first major awards-winner that partnered him with a then couple of unknown wunderkind actors/writers named Matt Damon and Ben Affleck as a sharp example of finding truth in stories as sensational as that of an MIT janitor who winds up solving the unsolvable equation at his school.

“There were experiences and characters that existed for Matt and Ben when they wrote it,” Van Sant says. “It wasn’t a documentary, but it had origin stories.”

The origin story of Van Sant’s latest film, however, is a bit unusual even for him. Coming to the filmmaker largely through the prism of a finished script by Austin Kolodney, Dead Man’s Wire approaches a breathless verisimilitude while telling the story of either the best day or worst in the life of Tony Kiritsis. Tony was a real, self-styled Midwest entrepreneur who, after feeling he was manipulated and preyed upon by a family of mortgage brokers, decided to kidnap the son on a February morning in 1977 by wiring the muzzle of a 12-gauge shotgun to the back of the man’s head.

In the ensuing aftermath of a two-day hostage situation, Kiritsis became a folk hero to some quarters of Indianapolis… including a jury.

“It was all new to me,” Van Sant says of the story that first came across his desk as a screenplay. “And as I was reading the script, I was learning that the scriptwriter had put hyperlinks within it, so that you could go to a YouTube page and it would bring you to a site that would play recordings or footage from the actual event. I realized it was super real.”

As a consequence, Van Sant found himself eager to stay relatively close to the historical record, including drawing from the 2018 documentary about the same event, Dead Man’s Line. In Van Sant’s version, Tony is played by Bill Skarsgård while the man he takes hostage, Richard Hall, is portrayed by an unrecognizable Dacre Montgomery; there are even tips of the hat to its 1970s cinematic inspirations with Al Pacino portraying Richard’s mortgage tycoon father as heartless and unforgiving—so the opposite of Pacino’s Nixon era antihero in Dog Day Afternoon (1975)—but the reality of the situation was paramount on Van Sant’s mind… even when he was taking liberties.

“Bill was quite a different physiological person, so we thought that going in a different direction was good,” Van Sant says about the central characterization. “I wanted him to be a sort of antic, changeable, moody, and funny character.” Van Sant left the voice and other acute physical choices to Skarsgård, perhaps feeling comfortable since it is the Swedish actor’s range in movies as varied as Barbarian and Nosferatu that convinced the director he could play one viewer’s madman as another’s Robin Hood.

The parallels between the anger in the culture of 50 years ago documented by Dead Man’s Wire and today are unmistakable, yet Van Sant would seem to caution reading too much into it.

“Right now, because of [Luigi] Mangione, yes, there are some similar things,” Van Sant acknowledges. “But I think just like Dog Day Afternoon is based on a real story, there are hostage-taking stories that have similar processes to them that just go back in history.”

Nonetheless, the way other processes are changing weighs as strongly on Van Sant’s mind as it does old collaborators like Damon and Affleck. When we catch up with Van Sant, it is shortly after comments were shared by Affleck and Damon about the ways Netflix has changed storytelling, including on their very own Rip. In effect, they seemed to suggest, we might be seeing the language of cinema shift.

“There’s a lot of observations to be made because of the streaming business and technology affecting cinema,” Van Sant considers. “I’m a big fan of a book called A Million and One Nights [by Terry Ramsaye], which was written in the 1920s. It’s kind of explaining the birth of cinema and the advent of sound, and how that affected the form. There was then an addendum to the book when sound came along, and it was about the change that happened between silent and sound films. We’re sort of going through that again with this technology change.”

Van Sant makes special note of how the format of film exhibition was always dictated, for better or worse, by commercial interests.

Says the director, “The reason I think that films were projected in the first place was that they were like originally on [kinetoscopes] or nickelodeons, which was a small screen that you would see in like an arcade or a shopping area. People would look at little passion plays on a small screen, and it was on a small screen because they didn’t really know how to project film without burning it. It would melt. So when they figured out how to [exhibit it in a larger format], it made sense business-wise that every time you showed it, to fit in as many people as you could. It made sense to have a crowd and to make it like a play, and now it makes a different sense to be able to send it to everyone’s personal computers. It’s a different technology.”

He continues, “We’re living in a different age where we don’t necessarily gather in the same place. So I don’t know if it’s good or bad, but I don’t think that people knew if it was good or bad when it was created. It was a business, and the businesses are usurping how we are used to cinema.”

Ultimately Van Sant compares the current transition to a bit like listening to music. One will have a very different experience when listening to a piece of music performed live by an orchestra versus listening to a recording of that same orchestra on their headphones. It’s still the same piece of music, however. For now though, Van Sant seems happy that by remaining a dedicated fixture of the indie landscape, he has avoided some of the same constraints and pressures that Damon described as being placed on other filmmakers.

“I feel like I’ve sort of [spent] my whole career outside of the commercial demands of, say, a movie that you might be spending $100 million on. With that movie, there’s a financial need to make the money back. Usually if my films are low-budget enough, the demands are less. So I haven’t been pushed into any decisions that I couldn’t accept.”

At the moment, the only sawed-off shotguns against the predations of capitalism in Van Sant’s world remain elements of Dead Man’s Wire. It is playing in cinemas now.

The post Gus Van Sant Sees Unlikely Precedent for Cinema’s Future in a Post-Streaming World appeared first on Den of Geek.