The 80s weren’t all completely awesome, and we aren’t just talking about St Elmo’s Fire. Some of it was flat out traumatising and, as is traditional, it was the fault of the bloody Germans. Only the type of people as obsessed with model trains as the Germans could have come up with this – The NeverEnding Story.

The NeverEnding Story – A Beautifully Weird Fever Dream

If you grew up in the 1980s, you already know The NeverEnding Story isn’t merely a movie. It’s an emotional booby trap disguised as a children’s fantasy film, engineered somewhere inside the strange Teutonic cinema labs of West Germany.

It’s the kind of movie that starts off whimsical and dreamy, and ends with you staring at the wall for an hour, wondering if happiness is even a real thing and whether horses have existential crises.

Understanding The NeverEnding Story is to understand how a country came up with both leather shorts and the final solution.

The NeverEnding Story carved out its own little kingdom among the decade’s fantasy-heavy landscape that was, if we are being honest, deeply fucking weird anyway. This was the golden era of kids’ escapist cinema that somehow went far too hard for no reason. Labyrinth had goblin infant theft, The Dark Crystal had vulture-bird-puppet fascists, and Return to Oz was made by people who clearly hated children and wanted them to scream themselves to sleep.

But The NeverEnding Story? It gave us a cosmic void that wants to eat reality like a sad, hungry black hole with clinical depression, and it came from Germany.

We start with Bastian, a kid who looks like he’s two weeks into an unpaid internship at an 80s hair mousse factory. He’s bullied, his dad doesn’t believe in imagination (classic cinematic father move), and then he does what any rational child does: steals a book from an old man and hides in a school attic full of asbestos and questionable taxidermy.

This sounds like the beginning of The Ring if you swapped the cursed VHS out for a leather-bound fantasy novel that wants to spiritually assimilate you.

Inside the book is Fantasia. This is not to be confused with Disney’s Fantasia, where the worst thing that happens is Mickey Mouse nearly drowns in broom-related unionization issues. No, this Fantasia is a bizarre, psychedelic world full of rock monsters, racing snails, bat-handlers, statues with massive fat cans, and whatever the heck the Skeksis’ German cousins are.

Fucking Germans, I tell ya!

Enter our hero: Atreyu, a kid warrior who looks like the kind of child who’d beat you in a staring contest and then steal your lunch money using stone-age intimidation techniques. He’s tasked with stopping THE NOTHING, because apparently, Fantasia’s HR department was on vacation that week and there were no adults available.

Atreyu’s job is simple: traverse dangerous lands, lose his horse, get emotionally wrecked, find a cure for the dying Childlike Empress, and hopefully avoid being eaten by a giant wolf that looks like it was Frankensteined together with leftover Muppets.

So… no pressure.

In the middle of all of this is the part everyone remembers. The moment the film turned from whimsical fantasy to generational trauma:

The Swamp of Sadness.

A swamp so depressing it kills you if you get too sad, which is exactly the kind of psychological landscape you’d expect German storytellers to invent, just before they slipped sensuously into an immaculately tailored Hugo Boss uniform to show us what real sadness felt like. Michael Ende, the author of the original book, was German to his bones, which is why half the movie feels like a philosophical debate about the meaninglessness of existence disguised as a children’s bedtime story.

And then it happens.

Artax. The horse. The myth. The legend. The equine poster child for therapy bills. Watching Artax slowly sink and die in quicksand while Atreyu screams at him to fight the sadness was the cinematic equivalent of your dog running away on Christmas morning.

Entire countries don’t have moments this traumatic in their national histories. Germany does, obviously, which is why thery are still apologising to this day, but normal countries don’t. Pediatric psychologists still bring this scene up at conferences.

There has never been, before or since, a horse death this devastating in kids’ media. Even Old Yeller looks at Artax and says:

“Bro, that was rough.”

The fact that the movie never fully recovers from this emotional ambush is part of its dark, unsettling, grisly charm. It turns The NeverEnding Story into a rite of passage. If you weren’t emotionally shattered by Artax’s death then, congratulations, you’ve probably grown up to be a premier league sociopath.

The NeverEnding Story was directed by Wolfgang Petersen, the famous German filmmaker who somehow thought children needed to experience metaphysical despair before puberty. Petersen’s entire vibe was:

“What if fantasy… but also emotional nihilism?”

Fantasia doesn’t feel like a typical movie world. It feels like the fever dream of someone who spent too much time reading Grimm fairy tales while trapped inside a dark Bavarian forest with only schnapps and hallucinogenic mushrooms for warmth.

Everything in the film has this slightly unhinged quality: The giant Rockbiter who eats boulders like they’re Pringles and steamrolls the scenery like a Panzer division. The racing snail that moves like a blitzgreig. A man who swoops around on his bat like a Messerschmitt.

It doesn’t stop there. There is a childlike Empress who talks like she’s in an avant-garde German art film, confronting her own mortality, a wolf puppet who looks like he belongs in a glam metal band, and a cultural strangeness that’s hard to quantify.

You watch the movie and can feel it’s not American. It doesn’t follow Hollywood rules. There’s no whimsical musical number to break up the existential dread. No comedic relief sidekick throwing out zingers. Just a slow slide into the emotional abyss wrapped in a children’s adventure film.

NeverEnding Mullet

No review of The NeverEnding Story is complete without mentioning what is arguably the most 80s thing to ever happen to human ears – Limahl’s theme song.

It is physically impossible to listen to this song without feeling like you’re inside a glittery laser light show while having the urge to rent this movie on videocassette from a vide rental store that hasn’t existed for 30 years.

Limahl, former Kajagoogoo frontman and full-time visual embodiment of the decade, delivered a track so aggressively 80s it practically smells like neon. The song is joyous, electronic, and somehow both uplifting and melancholic, and flat out fucking weird… almost just like the movie.

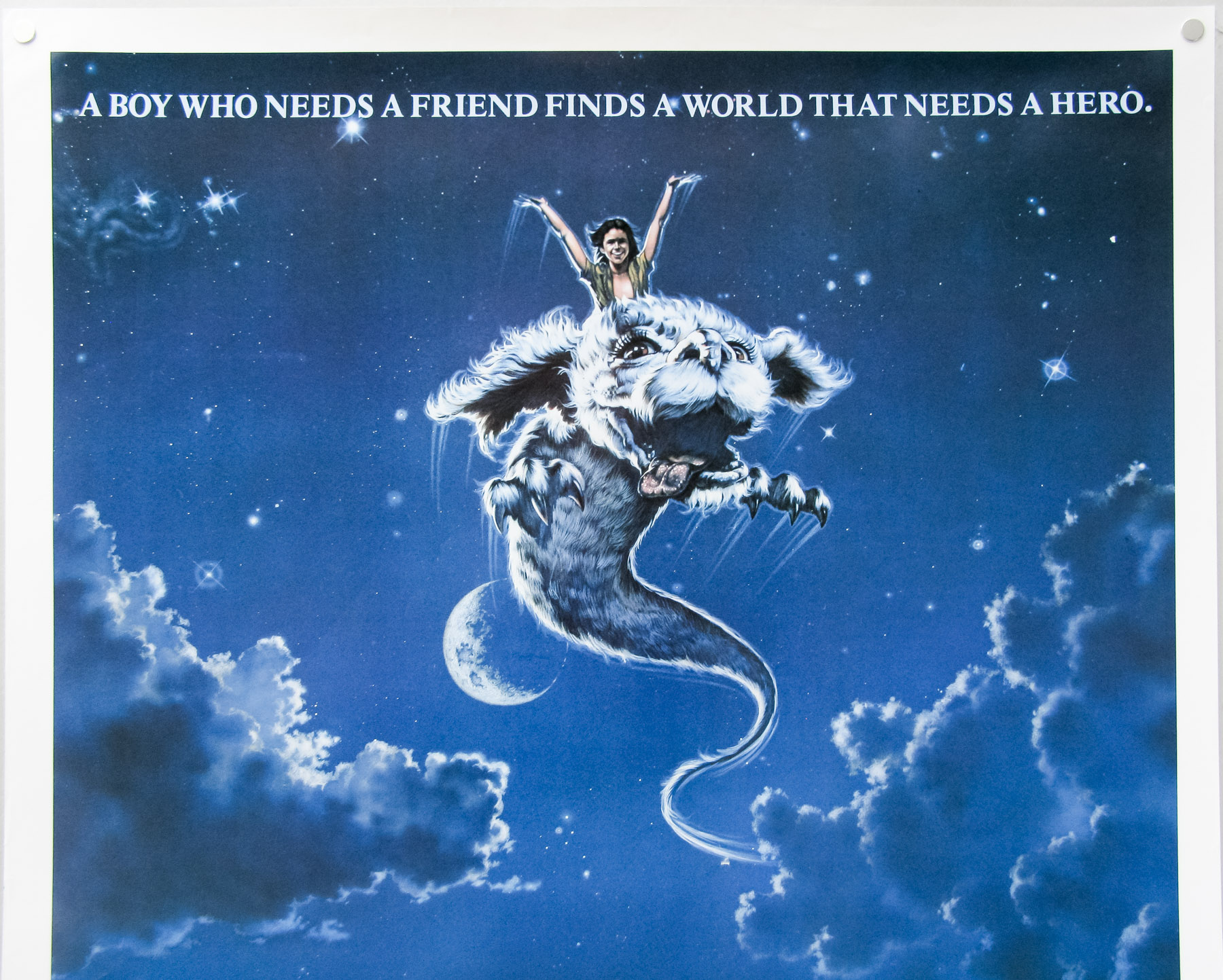

The music summons immediate and deep childhood memories of Falkor, the luckdragon. Part dragon, part dog, part nightmare fuel depending on your age and opinions about giant furry creatures staring directly into your soul.

Falkor is the cinematic comfort animal for an entire generation of future cat ladies. He’s fluffy, he’s supportive, he gives compliments, he rescues you from wolves, and he flies. He’s basically the ideal boyfriend for anyone who’s ever owned more than three cats at once.

The enduring affection for Falkor is not hard to understand: he’s like a giant, airborne golden retriever who runs on hopes, dreams, and whatever German puppeteers were smoking back in 1984.

A Movie Like No Other – Thank God

The movie stands apart not only from its peers but from pretty much anything else ever put on film. Even other 80s fantasy epics – Legend, Labyrinth, Willow, The Dark Crystal – don’t quite occupy the same headspace. Those movies are weird, sure, but they feel like they’re trying to entertain you.

The NeverEnding Story feels like it’s trying to teach you something about the fragility of all existence with muppets.

There’s a sincerity to it that’s rare. The movie doesn’t wink at the audience. It never apologizes for its earnestness. It doesn’t care if you’re confused. It just plunges ahead with its emotional monsoon.

The film was shot in Munich’s Bavaria Studios, then the largest studio complex outside Hollywood. The production spent a massive amount on practical effects and puppetry. Falkor was built as a 43-foot animatronic rig covered in dog fur. He reportedly smelled like a wet wool blanket after a few takes under hot studio lights.

Michael Ende, author of the original book, hated the movie. He tried to get his name removed from it.

Noah Hathaway (Atreyu) did many of his own stunts and was seriously injured more than once, including almost drowning—because apparently the Swamp of Sadness method-acted back, which is peak German energy.

This thing was built like a BMW: expensive, precise, occasionally dangerous in the wrong hands, and very, very German.

Then you have the villain that is not a villain – The Nothing.

You have to admire the confidence it takes for a kids’ movie to make the villain the concept of entropy. No masked sorcerer. No evil alien. No wicked stepmother. Just… the collapse of all meaning.

Nothingness. Cosmic despair.

The end of imagination itself.

And then the movie expects children to sleep afterward.

Kids understand fear of the dark, fear of being forgotten, fear of not mattering. The NeverEnding Story weaponizes that primal dread and turns it into an encroaching darkness that eats worlds and can only have come from the kind of imagination that also brought you Colditz.

In the end, The NeverEnding Story is equally one of the purest pieces of 80s fantasy ever produced, and one of the worst things inflicted on children since Josef Mengele. It is both wondrous and nightmarish. It’s surreal, moving, traumatizing, uplifting, and profoundly weird. It feels like reading a fairy tale while feverish. Yes, you will recover, but you wouldn’t voluntarily put yourself through it.

This movie shaped a generation’s imagination and neuroses in equal measure. It taught us that stories matter, grief is real, horses die for no reason, and if you believe hard enough, a dog-dragon might come pick you up for a joyride through the cloudy German skies, like a Stukka heading for a radar installation.

Would it be made today? Absolutely not. Modern studios would demand quips, self-aware jokes, and at least three dance numbers. But back then? They gave kids philosophy, depression, adventure, trauma, and existential dread all in one go.

I am just not sure we needed it. Not like this.

The post Retro Review: THE NEVERENDING STORY (1984) appeared first on Last Movie Outpost.