The Long Walk (2025)

The task is simple: Walk or Die

Francis Lawrence’s The Long Walk is one of the most viscerally confronting Stephen King adaptations — specifically from his Richard Bachman era — yet it manages a surprising amount of emotional weight. It’s a film that is often brutal, frequently bleak, but in its best moments deeply humane. King first published the novel in 1979 under the Bachman pseudonym, where he explored darker, more cynical visions of society — grim dystopias stripped of the supernatural. The Long Walk fits squarely in that mode: a chilling parable of authoritarianism and endurance that still feels uncomfortably relevant.

The premise is devilishly simple. Fifty boys — one from each U.S. state — line up on a desolate stretch of highway under the eye of soldiers and cameras. The rules couldn’t be clearer: keep walking at three miles per hour. Drop below that pace and you get a warning; three warnings in an hour, and you’re executed on the roadside without ceremony. The Walk doesn’t end until forty-nine are dead. The lone survivor claims “the Prize”: endless wealth along with anything he desires, a wish with no limits. That promise dangles like a cruel carrot, but the true horror is how quickly both the boys — and the audience — realize no reward could ever justify the cost.

The filmmaking in The Long Walk is lean, compressed, and deliberately relentless. Francis Lawrence — best known for The Hunger Games series — takes the spectacle out of spectacle and turns this into a purer horror of endurance. The film openly rejects world-building excess and glossy effects in favor of stark minimalism. Shot mostly with handheld and tracking cameras, the cinematography by Jo Willems keeps us locked at eye-level with the boys, trudging beside them mile after mile. Wide shots of the endless highway contrast with suffocating close-ups of sweat, fear and exhaustion, making the brutality land harder because there’s nowhere to hide: every mile walked, every slip, every shot feels immediate.

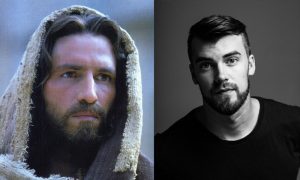

The cast really does all the heavy lifting. Cooper Hoffman — son of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman — carries the film as Ray Garraty, walker #47, with a quiet, wounded intensity that makes him someone you can’t help but root for, even when everything around him is designed to crush him. David Jonsson’s Peter McVries, #23, is the perfect counterbalance: harder, sharper, but cracked in ways that make their reluctant friendship the emotional spine of the story. And then there’s Mark Hamill as The Major — authoritarian, unsettling, a constant reminder that the rules are absolute. At times his bellowing through mirrored aviators edges toward caricature, but the menace is still there, hanging in every scene he appears. What really stuck with me, though, was Hoffman and Jonsson together: the chemistry, the quiet exchanges, the flickers of humanity in a nightmare designed to strip it away. That’s where the film’s heart beats.

A nation watches. He enforces.

Thematically, The Long Walk runs deep. At its core, it’s a study of authoritarianism and complicity: a society not just tolerating cruelty, but turning it into a national pastime. These boys aren’t plucked at random — they volunteer, either out of desperation, delusion, or some thin hope of glory. That choice is what makes the whole thing sting: they walk into the system willingly, even as it grinds them down mile by mile. It’s also about youth colliding with mortality, idealism cracking under despair, and the way survival strips away not just flesh but dignity. The film doubles down on surveillance — the boys march, the crowds observe, the soldiers enforce — and the uncomfortable truth is that the Walk only exists because people want to watch. That’s the gut-punch: it isn’t just about the walkers, it’s about the culture that demands the march in the first place.

And then there’s the violence — ever-present, unvarnished, and impossible to look away from. The film doesn’t flinch. Early on, when a boy cramps and stumbles, he’s executed on the spot. No warning speech, no dramatic pause — just a gunshot to the head and the Walk continues. Hank Olson, #46, played with raw volatility by Ben Wang, enters as one of the stronger walkers but becomes the film’s most painful descent. He starts off brash, even cocky, but the miles chip away at him until his mind fractures. His slow collapse — babbling, stumbling, lashing out — is excruciating to watch, and when the soldiers finally step in to enforce the rules with mechanical finality, it lands like a hammer blow.

Together now. Alone in the end.

By the time Garraty and McVries reach the endgame and square off with the Major’s authority, the violence has shifted from shock to inevitability — and that’s what makes it hit hardest. It’s not gratuitous; it’s baked into the fabric of the story. Every death is a reminder of the rules, and every mile forces us, the audience, to reckon with our own complicity in watching. That’s the true cruelty of The Long Walk: the brutality isn’t just on screen — it’s reflected right back at us.

In terms of comparison, the film shares DNA with The Hunger Games but strips away the pageantry — no parades, no talkshows — just slog, sweat, and silence. It’s closer in spirit to 2000’s Battle Royale or King’s The Running Man — though even those had spectacle. Here, the only “show” is the boys themselves being broken down, step by punishing step. They don’t even get called by their names anymore — just numbers barked by soldiers, tags on their shirts like cattle on a conveyor belt. That dehumanisation is the point. The Long Walk grinds down both body and spirit, and in King’s canon it stands tall — faithful, powerful, and mercifully free of the glossy missteps that sink lesser adaptations.

There are flaws. The world-building stays sketchy, giving us only scraps of why this society even supports the Walk, and some stretches of repetition might test the audience’s patience. The ending, too, sticks to the novel’s ambiguity, which means some will admire its honesty while others will find it frustrating. But honestly, these are small cracks compared to the weight of what works.

The Long Walk isn’t comfortable viewing. It’s harsh, unflinching, and all the stronger for refusing to soften its blows. The performances, the direction, the themes — they line up to create something rare: for once, a King adaptation that doesn’t feel like it tripped on its own shoelaces. Watching it, I couldn’t help but think: I’m a good walker. I’d love to test myself against that endless road, a single, merciless stretch — minus the rifles at my back, of course. And that’s the genius of the film. It makes you feel the pull, even as it shows you the cost.

4 / 5 – Recommended

Reviewed by Stu Cachia (S-Littner)

The Long Walk is released through Studio Canal Australia