Twenty years ago, Bill Murray sat perfectly center of frame in an ornate Italian theater near the Mediterranean. In the reality of this shot, he was portraying a storyteller within a story—a filmmaker named Steve Zissou, who after enjoying decades at the top of the international film scene has entered a fallow period. We later learn it’s been nine years since his last “hit documentary” and his reputation as a Jacques Cousteau-like oceanographer-turned-director died at roughly the same time as disco. Yet there he was still in the gilded halls that a filmmaker like Wes Anderson would recognize fresh off an Oscar nomination for his last movie, The Royal Tenenbaums.

In his follow-up, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Anderson begins his story at the glitzy world premiere of Zissou’s latest doc, Adventure No. 12: “The Jaguar Shark” (Part 1), a seemingly idyllic odyssey at sea until the sudden ending where Steve’s best friend and colleague, Esteban du Plantier (Seymour Cassel), is devoured whole by a so-called Jaguar Shark. We don’t see the death in the movie-within-a-movie, just a sea of gushing crimson as Steve splashes to the surface calling for his mentor. The sedate audience within the auditorium barely reacts.

In an obligatory Q&A following the screening, one of the only meaningful questions Steve fields is “was it a deliberate choice not to show the Jaguar Shark?” With his usual understated detachment, Murray responds, “No, I dropped the camera.” Only then does the crowd respond with a wave of giggles. “Why are they laughing?” Steve whispers to his moderator.

One senses Anderson could relate to the scene and Steve’s bafflement even before The Life Aquatic opened to what was at the time the worst reviews in his young career.

There is, indeed, something innately silly about the pretensions and decorum of film premieres, particularly for filmmakers carrying around as much prestige and baggage as Steve Zissou. And in The Life Aquatic, the intent is to create a character who’s bought into that hype enough to not only be perplexed by the arbitrary nature of fame and adulation, but also hurt and affected by its subsequent absence. When we meet Steve, he seems as much wounded by the critical reception of his latest doc as he is by the death it preserved for all-time. Even so, he insists in the same scene he knows what his next film must be about: like Ahab he will hunt down and kill the fish that hurt him.

“What would be the scientific purpose of killing it?” he is asked. “Revenge.”

It’s a hell of a line that still slays thanks to Murray’s natural aloofness matching Anderson’s visual deadpan. And it is a piece with Anderson’s best films, which in our estimation also include Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, and The Grand Budapest Hotel. Unfortunately, ever since its own real-life cool reception, The Life Aquatic has rarely been mentioned in that company. To this day, it even sits at a glum 57 percent “positive” on Rotten Tomatoes. But after the film’s 20th anniversary last month, it is time to finally give Steve the flowers he so desperately craves. It is time to put Life Aquatic on the A-squad.

A Filmmaker Trying to Build His Little World

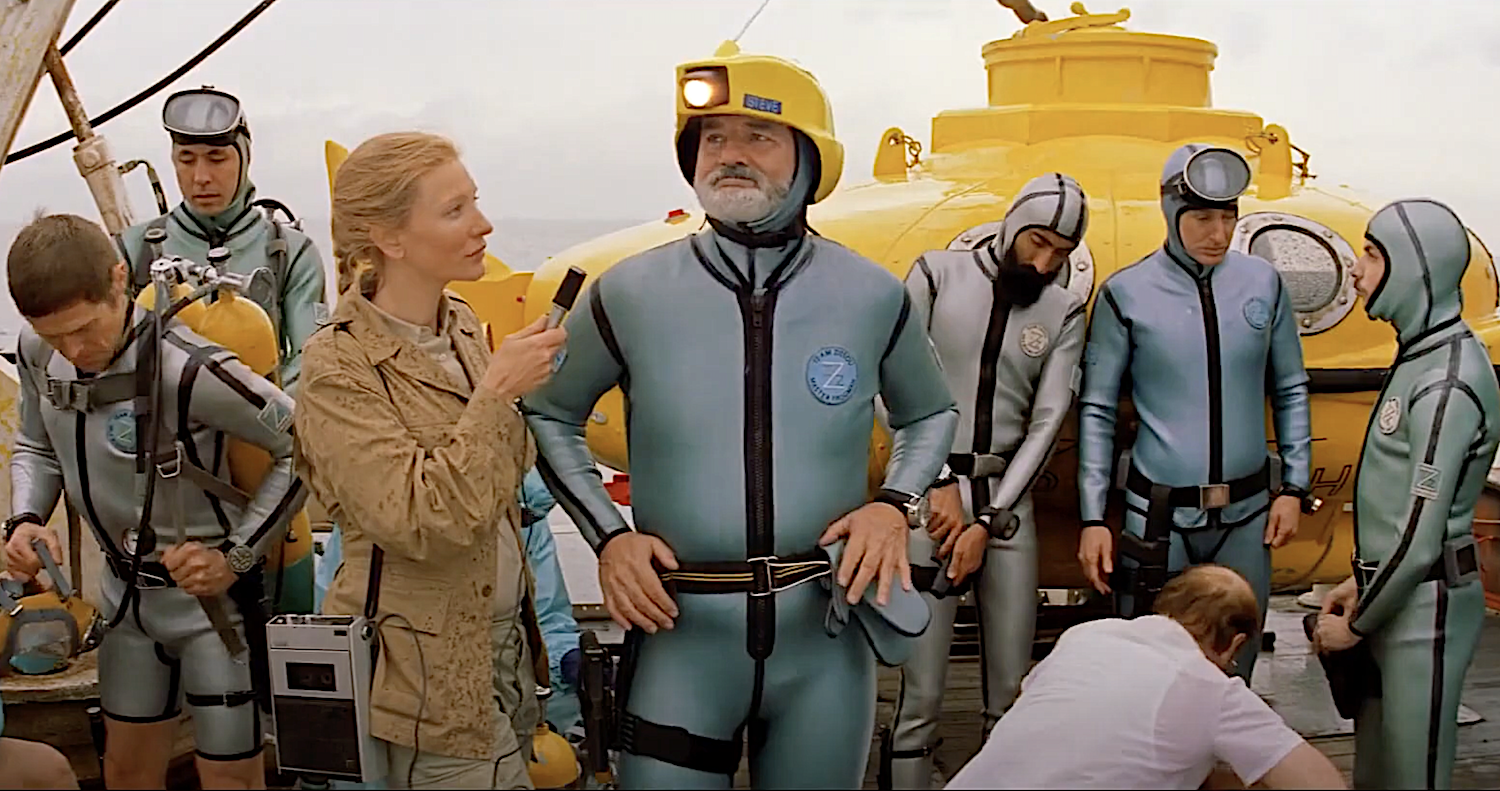

By design, The Life Aquatic invites the audience to see the parallels between the characters of “Team Zissou” and Anderson’s own band of tight-knit collaborators. For instance,The Life Aquatic’s cinematographer, Robert D. Yeoman, has been with Anderson since the beginning on Bottle Rocket in 1996, and that’s carried on through 2023’s Asteroid City and “Henry Sugar” short films; Murray of course first appeared in Rushmore in 1998 and has turned up in nearly every Anderson joint since; and costume designer Milena Canonero began a collaboration with Anderson here, building a foundation to a relationship that’s lasted also through Asteroid City.

Anderson knows what it means to be a storyteller who assembles a trusted team. But at least when Life Aquatic came out, he didn’t know what it meant to be a middle-aged artist who the press had turned on. That’s because he was not making a film about himself in 2004… or at least not about his process for making movies. The more interesting reading of The Life Aquatic’s setup is instead about how it studies just one fundamental muse of any director: the ego, and all the absurdity it and “auteur theory” invites in.

Anderson’s movies are of course unmistakable. His affinity for symmetrical compositions, often while featuring pleasing straight lines and patterned set designs, are instantly recognizable. And they’ve become virtual case studies in understanding what an “auteur’s stamp” means for film students around the world. But they are not the beginning and end of his vision. In fact, they’re often just supplemental expressions of the broader stories and worlds they inhabit. They are extensions of characters who are trying to control their world via manners and affectations as tidy and beatific as Anderson and Yeoman’s framings. By and large, these characters are also men who yearn to live in a world of artifice. And save perhaps for the bitter reality that creeps into M. Gustav’s 1930s grand hotel, Steve Zissou’s search for his own white whale is Anderson’s frankest admission to the limitations of these daydreams.

What makes The Life Aquatic both so funny and tragic is its portrait of a sad, vain man who cannot control anything in his life despite forcing everyone around him to be branded with his mark. Whether it’s during a paramilitary rescue operation on a pirate-infested seaside resort, or the aforementioned film premiere, each and every character is forced to wear Steve’s bright red beanie as if they were serfs subject to his beneficence. And when he decides to accept a sweet man named Ned Plimpton (Owen Wilson) as his long-lost adult son, he immediately demands this grown adult also don the hat, the blue swim trunks, and eventually Steve’s last name in spite of the fact that Zissou refused to meet Ned 30 years prior.

Steve lives in a wonderful Anderson world where all the fish, including that loathed Jaguar Shark, are claymated confections colored in pastels, or lit with inner-luminescence as seen in the glowing jellyfish on an Italian beach. Steve captures it all in his (and Anderson’s) own pleasing image. Think of the tour de force tracking shot of Steve’s ship, the Belafonte, which through clever set design, animation, and camera movement is revealed to have a gourmet kitchen located right next to a library stocked with first editions, and an editing bay/recording studio where 35mm assembly cuts of his films can be spliced together on the day.

Anderson tracks the immaculate beauty of this world with a gliding tracking camera on an elaborate set-build that’s revealed behind a rising curtain. After the showstopper is done though, the camera pulls back and the light on the obvious soundstage where much of this was built is dimmed. Steve has constructed a magnificent but insular bubble around his life. It’s his own little world that is as beautiful, and fleeting, as a night at the theater. When the show is over, there is nothing left to experience.

And when the curtain is down, the reality is also not nearly so clean. In fact, the first time Anderson indulges another of his signature tracking shots, following Steve across the real upper deck of a ship that is supposed to house all these wonders, the pacing is harried and the energy frantic, as underscored by the crescendo of David Bowie’s “Life on Mars.” Moments earlier, Steve was forced to realize he has just met the thirtysomething man who might be his son, and his bubble is burst. He flees across the deck to escape the reality of the moment, hiding against a railing that is lit by Christmas lights. Nonetheless, all around him is darkness.

Later the clash between Steve’s perfectly curated fantasy of what he thinks his life is, and the bitterness of real life-and-death stakes outside that pretty picture, comes to a surreal head when pirates board his ship and spill intern blood on the Belafonte’s decks. They also trapp Steve and his crew in a brutalist desaturation uncharacteristic of most Anderson films. When Steve is able to take control of the situation by grabbing a gun and going Rambo long enough to save everyone except his Bond Company Stooge™, the colors return to the warm oversaturation we’ve come to expect from the film, but it is still a lie Steve is telling himself—one as delusional as thinking getting “revenge” on a fish will bring meaning to his sadness and midlife ennui.

In the end, Steve even claiming Ned as his son is a fallacy; we learn from his long-suffering wife and producer, Eleanor (Anjelica Huston), that Ned cannot be his child because Eleanor discovered years earlier that her husband is shooting blanks. Apparently he spent too many days in a wetsuit. By this point though, Ned’s dead, and like everything else about this sad, “great” artiste’s life, Eleanor is letting him live in a fantasy divorced from the colder truth around him.

Out to Sea with Amazing Collaborators

Thematically, The Life Aquatic is a richer film than it often gets credit for, but it is also a hilarious one that marked the last of Anderson’s early nimbler efforts. Like Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, and The Royal Tenenbaums before it, Aquatic was written in collaboration with another filmmaker with his own distinct sensibility, in this case Noah Baumbach a year before breaking out as an indie darling in his own right via The Squid and the Whale.

The future co-writer of movies like Frances Ha and Barbie pairs well with Anderson, complementing the Texan director’s usual melancholic nostalgia for bygone curios and eras of pop culture—in this case 1960s and ‘70s Cousteau documentaries—with the kind of narrative freewheeling nature that enlivens most of Baumbach’s comedies. In other words, The Life Aquatic’s script takes delightfully weird detours and swerves, such as when those pirates commandeer the ship, massacre all the boy toys of rival documentarian Alistair Henessey (Jeff Goldblum), and then invite a climactic rescue mission where Steve goes back to save that goddamn Bond Company Stooge like this was the third act of a 2004 Bruce Willis movie.

Through it all, the ensemble of actors are fully served by the screenplay in a way which has escaped Anderson’s most recent 2020s feature films. Cate Blanchett’s journalist Jane Winslett-Richardson allows the actress to do the rare thing and abandon her naturally regal Australian accent for a nasally Londoner lilt; she is a pregnant woman in desperate search for a good story and “a baby for this father;” Wilson likewise was cast against the type he embraced in his previous Anderson collaborations by here playing a square, straight-as-an-arrow former military pilot of a Midwestern disposition; and of course Huston and Goldblum are on hand to offer their usual charms.

My personal favorite remains Willem Dafoe as Klaus Daimler, the anxious and overeager hanger-on that clings so desperately to Steve’s coattails and favor that he stops in the middle of a gun fight to sulk, “Thanks a lot for not picking me…. I’m sick of being on B-squad.” It’s one of the script’s many golden lines, up there with Steve telling his interns, “I’m not going to flunk you but I can’t give you full credit either. You’re all getting incompletes;” and Goldblum shrugging, “We’ve never made great husbands, have we? Of course, I have a good excuse. I’m part gay.”

The Most Bill Murray of Wes Anderson Films

Above all else, and the other brilliant castings like Michael Gambon as Steve’s dubious agent and Brazilian musician Sue Jorge as Pelé, Team Zissou’s resident David Bowie cover artist, The Life Aquatic remains ultimately Anderson’s tribute to his most frequent collaborator in front of the camera, Bill Murray.

The relationship between the two has been long and fruitful, beginning in Rushmore where Murray played the unlikely romantic rival to a diabolical teenager (Jason Schwartzman), and it continues to this day. The Chicagoan actor’s naturally sardonic, and sometimes withering, comic timing proves a perfect weapon for Anderson’s own sense of visual drollness, and its killing shots can be delivered wryly, cruelly, and even pitifully, a la Murray’s aged and unlikely older husband to Gwyneth Paltrow in The Royal Tenenbaums or his enraged mild-mannered father in Moonrise Kingdom.

But those are all supporting roles, and sometimes little more than cameos. In The Life Aquatic though, Anderson crafted a starring vehicle for Murray that leans into the actor’s acerbic wit as well as the wistfulness which only began being noticed by critics in Rushmore and then in the best performance of the actor’s career, courtesy of Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation. Steve Zissou is not quite so perfect a second-skin for Murray as Bob Harris, but he still fits Murray like a glove (or slimming wetsuit), whether it’s when Steve is attempting to look cool in front of a reporter while grooving to music piped into his underwater gear or in a moment where the character can no longer put on any airs as he mourns the man he thinks is his son in front of the same woman.

It’s a poignant creation between director and muse that makes The Life Aquatic a milestone film in both men’s filmographies.

Portuguese Bowie

Finally, The Life Aquatic also still features Seu Jorge singing acoustic covers of David Bowie classics in Portuguese, often with Jorge’s own lyrics invented on the day. That’s cool enough for its own subhead.

The post The Life Aquatic Is Wes Anderson’s Most Underrated Movie appeared first on Den of Geek.