This article appears in the new issue of DEN OF GEEK magazine. You can read all of our magazine stories here.

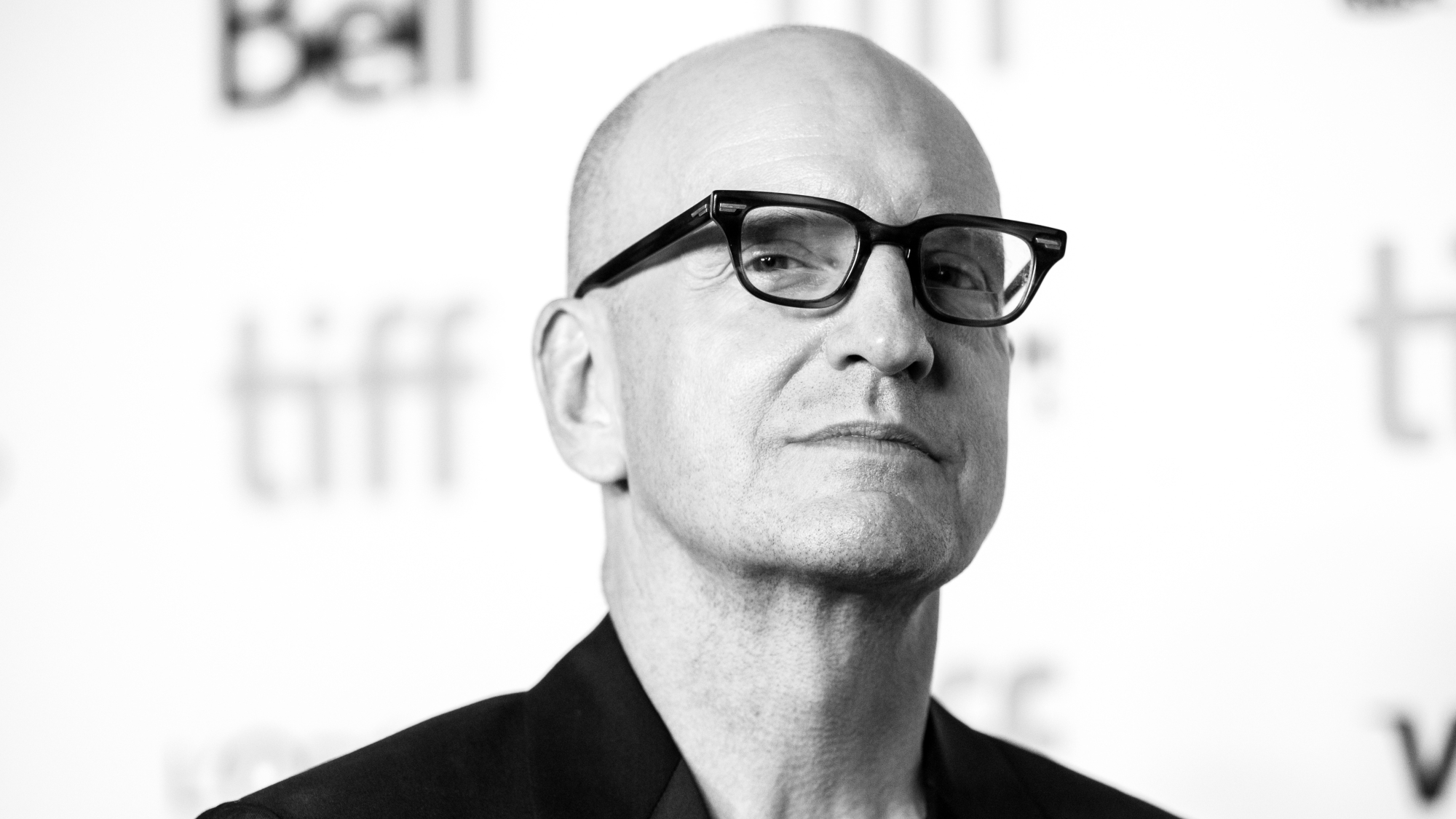

“I like to have fun, you know?” Steven Soderbergh has clearly been having a ball directing over 30 feature films (averaging one per year) since his auspicious 1989 Palme d’Or-winning debut, Sex, Lies, and Videotape. That body of work has been anything but predictable, from pulpy crime movies (Out of Sight, The Limey) to sci-fi (Solaris) to comedies (Let Them All Talk) to sports flicks (High Flying Bird) to eccentric biopics (Che, Behind the Candelabra). Arguably, the only genres he hasn’t tackled are Westerns and children’s movies.

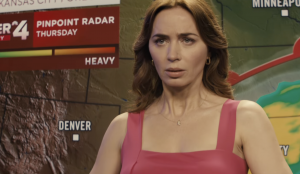

“There’s a larger chance of me doing a pure kids’ film than me doing a Western,” Soderbergh admits. He’s responsible for two wildly successful commercial trilogies—Ocean’s Eleven and Magic Mike—while also prone to experimentation, as with his new film Presence. Ostensibly a horror movie, Presence breaks the mold via the brilliant conceit of having the entire story shot from the POV of a ghost haunting a suburban family’s home.

Shot in sequence over 11 days (with the director filming the ghost POV himself while wearing quiet slippers), Presence was the toast of this year’s Sundance Film Festival, where it sold to distributor Neon for $5 million. When it opens this January, it will be a test of Soderbergh’s latest creative bet, but as someone who works constantly by treating filmmaking “like a sport,” that bet has already paid off. “I’ve never made anything I wouldn’t have made for free,” Soderbergh tells us while finishing his spy movie Black Bag in London. “If I’m not excited to be there, then I’m not going to be there.”

Soderbergh is not only cognizant of keeping himself on his toes creatively, but he’s also savvy about the business. This partially stems from the period after Sex, Lies, and Videotape, when he made three massive box-office failures in a row: Kafka, King of the Hill, and The Underneath. It forced him to rethink his approach, which led to an eventual reversal of fortunes in 2000, having two big hits in one year, Erin Brockovich and Traffic. The latter netted him the Best Director Oscar. Since then, he has deftly alternated between smaller esoteric films and bigger commercial ventures in true “one for them, one for me” style… even though he claims “they’re all for me.”

“Sometimes you need the juice of a hit to talk somebody into something that doesn’t look down the middle,” he explains. “You have to be strategic about that because too many weird ones in a row begin to affect your ability to get more commercial jobs.”

Presence may be the perfect combination of indie spirit with commercial appeal, especially with a screenplay by Steven Spielberg’s go-to closer, David Koepp (Jurassic Park, War of the Worlds). Having previously collaborated on the thriller Kimi (partly inspired by Koepp’s work on David Fincher’s Panic Room), Soderbergh and Koepp’s history in the horror/thriller genre as well as with each other goes back to the start of their careers.

At one point, you and David Koepp were working on a remake of The Uninvited, a classic gothic ghost tale that shares a lot of notes with Presence, including a brother-sister dynamic.

I’ve known David a long time. We both had movies at Sundance in 1989. He had a very close relationship with Universal, so it must have been his idea, initially, to tackle The Uninvited. We were making real progress and had come up with some interesting/weird stuff, then got hung up on the “Harold the Explainer” scene. I didn’t want to do one. He was like, “You have to do one.” I said, “But they always suck.” He’s like, “You have to explain why this is happening.” So we walked away but stayed friendly. Many years go by, and we had this incident and backstory connected to a house in Los Angeles where my wife and I stay. I wrote eight pages of an opening for Presence and sent it to David. He said, “I know exactly what to do with this.”

I read an unproduced script Koepp wrote about a supercollider. Having no association with a finished film, you could see how airtight/precise his scripts are. Your naturalism tends to mask a lot of those script mechanics in a complementary way.

That’s one of the reasons our collaboration has gone so well. I trust his extremely high level of craft and gift with the architecture of pure movie storytelling. The few notes I end up having with David involve that nine percent of the project where we don’t overlap perfectly. One example on Presence would be the original version of the scene where the psychic visits the family, which was more traditionally theatrical. My mother was a parapsychologist, so I pushed for something naturalistic: this woman has a day job at Home Depot and doesn’t do this as a business. She has this gift and is convinced to come to the house. The audience doesn’t view her as a kook or a flake. That’s me wanting to keep it from being too caricatured.

A stealth “Harold the Explainer” scene…

Exactly. She does a lot of heavy lifting, but it’s disguised well and allowed me to directorially do something interesting with her looking into the camera from the moment she walks through the door and is confronted with the presence, constantly keeping her eye on it.

Terry Gilliam said he doesn’t like shaky handheld shots because they don’t present the way our eyes perceive things. He prefers Steadicams or cranes or static wide angles. How much were you thinking about the way human perception works while shooting Presence?

Technically, he’s correct. Our brains and our eyes have the world’s best stabilization technology. It’s an open question amongst directors whether or not all point-of-view shots should be done in studio mode as opposed to handheld. I’ve come to the conclusion that studio mode is the way to go, even though I have shot POV off the shoulder. The case here in Presence was pretty straightforward, laid out in those eight pages I sent David, where I described exactly how the point of view worked. During prep, I experimented with different cameras and stabilization devices. We ended up with the Sony A7 camera and one of the Ronins, which is pretty small, a U-shaped thing you hold in front of you with each hand, very light. Going up and down stairs was tricky, but I really enjoyed the demands that approach required. Every scene was a single shot, scheduled in chronological order as much as possible because it was important you felt the presence evolve in the way it looks at things. There were a couple of long takes where we would be almost all the way through, and somebody would get up and move. Because I’d seen the scene before, I instinctively anticipated it. I would have to go, “Cut, my fault. I fucked that up.” It was fun, but it was tricky.

When you were threatening to retire about a decade and nine films ago, according to Matt Damon, you said, “If I see another over-the-shoulder shot, I’m going to blow my brains out.” This POV concept gave you a great excuse not to do any conventional coverage. Was that part of the appeal?

Yeah. In this case, it really was a directorial gimmick that I’d never employed to this extent, and it was exciting. At the same time, there’s no plan B. If it doesn’t work, you’re screwed. There’s no alternative way to shoot it. I had to believe the normal reaction to seeing first-person narratives, which is a desperate desire to see a reverse—to look into the eyes of the protagonist—would be mitigated by the fact that they know there’s nothing to cut to…. The protagonist doesn’t have any eyes.

You keep not only the visual perspective of the ghost but the aural perspective. All the dialogue stays at the same volume, whether the living person’s in the room right next to the ghost or in the driveway outside as the ghost looks through the window—it’s all the same pitch.

I talked to the sound team about that a lot. It doesn’t make any literal sense, but to be naturalistic about the sonic aspect of the film just seemed boring. A practical reason for that is your only understanding of the story is backfilling based on what people are saying. The audience should never be struggling to hear this dialogue.

Your abandoned version of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. with Scott Burns sounded really cool, this race to hunt down lost nuclear bombs. Now that you’re finishing up Black Bag, back to the realm of the spy thriller, have you been able to resurrect any of the stylistic ideas you had for U.N.C.L.E.?

Not really. There was a very specific take on that material. Visually, I was going to be a lot trickier than I am on Black Bag. Ours was a period piece; this is contemporary. While it had some demands, directorially, that kept me up at night, ultimately, Black Bag required a form of directing that is invisible. If you’re a filmmaker and you get to the end of this 12-page dinner scene that occurs early in the film, you’ll go, “Wow, 12 pages of people sitting at a table, not moving. That’s hard to make cinematic.” That was one of the scenes worrying me, but for an audience, it’s not a case of me waving my hands at them. It didn’t feel like that kind of movie. Whatever game I was building for that version of Man From U.N.C.L.E. got left by the side of the road. I like to not waste things. Some of those ideas may show up in something because there were a couple of technical things I was thinking about in terms of action sequences I was going to try.

Every entry in the Ocean’s trilogy has this quality of, “We’re gonna have fun and that’s going to translate to the audience.”

The feeling that comes across between the characters is legitimate. That was a uniquely wonderful cast, and they had a great time together. They were harder films for me than they were for them because no one person has to carry the whole movie. If you ask George what was fun about those movies, he goes, “My job every day was to give the scene away to somebody else.” He’s a real leader in life, the way Danny is in the movies. That’s legit. I viewed Ocean’s as these Lichtenstein panels, almost graphic novels where I got to use big, bold, colorful imagery—operatic, Baroque—and that’s not always appropriate. No guns to speak of. Nobody dies. They’re not violent, except for a little language. Your family can watch these. I was really proud of those. We were able to do three of them in six years and keep everybody together… that’s hard to do.

One of the reasons you did the initial movies you did after Sex, Lies, and Videotape was you didn’t want to be pigeonholed. The Underneath was a nadir—as you’ve said—except you did wind up making at least seven heist movies. Do you think Underneath was such a low point that you’ve subconsciously been trying to get it right in all these other heist films?

You make a good case. I don’t think so, only because I was so disconnected from myself while I was doing it that it’s hard for me to ascribe any conscious intention to it. It was taking me down a path that really didn’t play to my core. I was in danger of becoming a formalist and I didn’t want to be that, which is why I hatched a plan during shooting to go back to Baton Rouge to make Schizopolis with the people I grew up with. I reached out to Richard Lester, whose films had the kind of energy I wanted to reconnect with. The Underneath was one of the most important things I ever did because it forced me into teardown mode. Schizopolis is like my “second first film” in that it was designed to annihilate everything that had come before it, and it did.

Do you think Sex, Lies, and Videotape predicted the insular, onanistic sexuality of the internet age in the sense that what Graham (James Spader) is doing would not be considered taboo anymore in the OnlyFans era?

Oh my god, yeah. It feels like a Jane Austen novel compared to what’s going on now. It seems quaint, but it’s operating from a position of technology being used as a way to avoid connection, as opposed to creating it. The ability we have now to re-experience and regurgitate something over and over again. He keeps revisiting these “conversations” he’s had with these women, as opposed to being out in the actual world. That impulse is understandable; I was just amplifying it. It’s a sensation I have felt at times, “Wouldn’t it be easier and safer to stay in this bubble?” The funny thing was the assumption that stuff in the movie happened to me. While it was personal insofar as the issues it was grappling with, nothing in that movie actually happened to me.

There are very few genres that you haven’t tackled, but would you consider doing a children’s movie someday?

Yeah, I don’t think I’ve ever done a pure… I mean, King of the Hill is certainly something young people could watch, although it’s a little harrowing at times. But yeah, that would be interesting…. I think you have still gotta be tapped into that ability to see the world in those terms. What makes Spike Jonze’s movies—or anything he does—so fantastic is there’s something childlike about the way Spike sees things that is not a pose. What’s that line from Six Degrees of Separation? Where he’s talking about going into this children’s art class, all four or five years old, and he goes, “Everything these kids are drawing is a Kandinsky because it’s pure”? They don’t even know what any concept of art is, and they’re just making this brilliant thing. Spike’s able to do that. It’s a real gift.

You’ve talked about how when directors get together, inevitably, the idea of being in decline comes up. A lot of early films by male directors are about older men in decline. Even your second film, Kafka, is about a dying artist in his 40s. You made that in your late 20s. Is legacy an idea that gets into a director’s head from the start?

Part of your education is to study the careers—and, by extension, the lives—of filmmakers you admire and who you’re stealing from. With few exceptions, there tends to be a drop-off. The earliest indicator is when a male director makes a movie about the restorative powers of a young woman. The factor that seems most common is an inability to evolve combined with an attempt to recapture what they thought people liked earlier. I’ve tried to sidestep that as best I can by consciously looking for challenges, different stories, and different ways of telling them so that the thing I’m working on destroys the thing that came before it. My natural restlessness and the fact that I get bored easily help in that effort to keep chasing something instead of trying to recreate something from before. I want to be scared. There’s got to be something about whatever it is that scares me because it keeps me alert.

Presence opens in theaters on Jan. 24, 2025.

The post Steven Soderbergh on the Unique Horror of Presence, Making a Spy Thriller, and Seeking New Challenges appeared first on Den of Geek.