Toward the end of Star Trek: First Contact‘s first act, an away team from the USS Enterprise describes their world. “Mankind [starts] exploring the galaxy,” LeVar Burton’s Geordi La Forge declares. Deanna Troi (Marina Sirtis) continues, “It unites humanity in a way that no one ever thought possible. When they realize they’re not alone in the universe, poverty, disease, war—they’ll all be gone within the next 50 years.”

These descriptions ring true to anyone who has seen Star Trek before. Ever since Gene Roddenberry created the first episodes back in 1966, the franchise harnessed a Kennedy era optimism while building a united future, one where humanity’s petty distinctions fall away and they work together for a greater good.

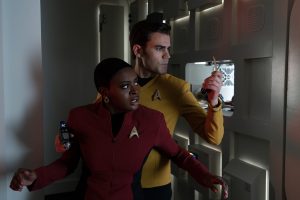

But Star Trek: First Contact also acts more discretely as a reminder that such a future does not come easy. After all, La Forge and Troi, along with Commander Will Riker (played by Jonathan Frakes, who also directs), deliver this prophecy to Dr. Zefram Cochrane (James Cromwell). Like all Starfleet personnel, the trio knows Cochrane as the visionary who invented the warp drive and inaugurated the new age of exploration and peace when he launched his ship the Phoenix. But thanks to the movie’s time travel conceit, our heroes now find the real Cochrane to be a drunken failure, with none of the inspiring qualities they expected.

So while much of the movie revolves around Picard dealing with his trauma, and Worf dropping one-liners while blowing away the Borg, the heart of First Contact becomes about considering the real, messy work that goes into building a utopia.

Before First Contact

As the first solo film featuring the crew from Star Trek: The Next Generation, First Contact finds the USS Enterprise-E following the Borg back to April 4, 2063. The Borg have gone back in time to prevent “first contact,” the day that Cochrane’s inaugural warp drive flight catches the attention of the Vulcans, making way for Starfleet and the Federation.

Cochrane, Trek fans know, was a legendary figure in the mythos long before he showed up in the film looking like the jolly farmer from Babe. He originally appeared in the season 2 Original Series episode “Metamorphosis,” played by Glenn Corbett. There, Kirk and Spock find Cochrane restored to youth and alive for centuries thanks to an entity called “the Companion.” Though lovelorn, this Cochrane has the dignity and optimism that meets Kirk and Spock’s expectations, a true hero who led humanity into the future.

Not so when the Enterprise-E away team meet Cochrane in 2063. The ever-awkward Reginald Barclay isn’t the only one whose hero worship freaks out Cochrane. La Forge exacerbates things when he rhapsodizes about attending Cochrane High School and the impressive statue that humans will later construct, one 20 meters high and featuring the doctor looking to the sky with inspiration. Cochrane realizes the irony at work. Apparently he inspires the world. But he can’t even inspire himself. The more that La Forge et al. tell Cochrane about the man he’ll be come, the more the man he is shrinks away. In fact, it takes a phase blast from Riker to prevent Cochrane from abandoning the project altogether and running away.

He sees the vast gap between the future described by Riker and the world in which he lives. Instead of working to bridge it, Cochrane collapses.

A Communal Effort

Cochrane’s response actually makes a lot of sense. It’s not just that the world described by the Starfleets sounds too good to be true. It’s that they make it sound like it all came from him, that he was the one thing that changed it all. Cochrane’s right to fear such individualist hero worship. No one person could shoulder such a responsibility, even one as brilliant as him.

Yet the actual Cochrane plot in First Contact shows that, in fact, he didn’t do it alone. Even if they don’t get lines, background characters in the Earth scenes show a crowd of people at work, actually enacting Cochrane’s designs. In a fun bit of time look paradox shenanigans, La Forge asks Cochrane to confirm a part of the Phoenix, implying that maybe La Forge got the idea from something he read in the future about what he would actually do in the past, even if the textbooks credited it to Cochran.

It’s not just physical labor that makes the Phoenix fly either. Cochran needs Riker and Troi and La Forge to inspire him, to reassure him, to help keep him on task. Of course Cochrane’s used to such behavior, as demonstrated in his first scene in the movie. As he stumbles drunk out of a bar, cut off by the tender, it’s his friend Lily (Alfre Woodard) who keeps driving him forward. Lily keeps Cochrane focused and Lily provides the support.

Lily continues that work when she separates from Cochrane and ends up on the Enterprise with Picard (Patrick Stewart), fending off the Borg attack. Like Cochrane, Picard approaches his problems from an individualist standpoint. He sees the Borg attack as an assault against him and imagines himself as the one person who can stop it. Even as the movie sets off Picard’s inadvisable transition into an action star, a quality exacerbated in the next two films, it also understands that the problem isn’t about him.

Lily forces Picard to face his fears and to look beyond himself, to look toward the greater good. And it’s through Lily’s determination and help that Picard becomes the hero who saves the day. With a little help from an android named Data.

The Continuing Mission

As much as Star Trek: First Contact emphasizes the communal work of making the future, it cannot avoid the irony that it’s only Cochrane who gets a statue. We might be able to accept that the history books would avoid mentioning the intercession of “astronauts… on some kind of star trek” (to use the clanger of a line from the script by Brannon Braga and Ronald D. Moore). But it’s impossible to justify the fact that the work of a Black woman, especially one played by the magnetic Woodard, gets ignored. Especially since it’s suggested that if not for the Borg’s intervention in the past, Lily instead of Riker and Geordie would have been on that fateful warp drive flight. Yet no one in Starfleet seems to know her name.

Of course First Contact also provided a critique of the franchise’s own mythos, with the scared and drunken Cochrane standing in for Rodenberry, a man of many flaws who created something wonderful. Roddenberry’s hardly the only problematic figure that made Star Trek what it is (I mean, First Contact is a Rick Berman production), but it would be as much a mistake to put all of the franchise’s failures on one person as it would be to attribute that individual with all the successes.

First Contact itself is an imperfect work, but that’s the point. Going from a state of despair and hopelessness to one of utopian improvement is filled with mistakes and misgivings, the type that can only be overcome by a community working together. It’s not as neat an image as a marble statue of a single great man, but neither is reality.

The post Star Trek: First Contact Still Shows the Real Work That Goes Into Building a Utopia appeared first on Den of Geek.