The Main Slate of the 62nd New York Film Festival features everything from early features by promising young filmmakers to late-career gems from some of the industry’s most legendary auteurs. And while it’s easy to gravitate towards the more traditional “big names” on the list, you shouldn’t miss the opportunity to get to know the work of some truly exciting up-and-coming directors. Read on for my thoughts on two films from emerging female filmmakers that were some of the highlights of this year’s festivalgoing experience.

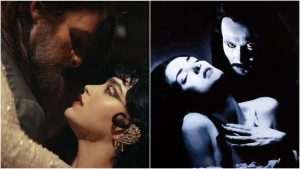

All We Imagine as Light (Payal Kapadia)

The narrative feature debut of writer-director Payal Kapadia and the first film from India to win the Grand Prix at Cannes, All We Imagine as Light is an evocative drama exploring love, loneliness, and female friendships amidst the heaving crowds and glittering lights of Mumbai. Indeed, the Mumbai setting is just as much of a main character in the film as any of the human beings who appear on screen, so much so that Kapadia introduces us to the city first, beginning her film with a montage of street scenes overlaid by different voiceovers explaining why so many people choose to leave home and come here to make a new life. It’s a place of opportunity and of employment, but also of isolation: the kind of place where you can be physically surrounded by millions but emotionally still so alone.

source: Janus Films

The film centers on two nurses who happen to be roommates: practical, respectable Prabha (Kani Kusruti, also so impressive this year as the complicated mother in Girls Will Be Girls) and passionate, impetuous Anu (Divya Prabha). Prabha, the elder of the two, has not heard from her husband—away working in Germany—for close to a year; she’s so lonely that when he sends her a rice cooker out of the blue, she gets up in the night to wrap her arms around the cool metal and cry. A kindly doctor at the hospital where the women work is interested in her, but Prabha is too reluctant to admit that her marriage is over to give him any hope.

Meanwhile, Anu—still young enough to not yet be jaded—is involved in a passionate secret romance with a Muslim boy, arranging trysts in parking garages and parks while fending off suggestions of approved suitors from her parents. When a widowed colleague and neighbor (Chhaya Kadam) has to give up her flat and return to her home village by the sea, Prabha and Anu accompany her to help with the move; the resulting journey is a much-needed emotional awakening for all.

A film suffused with tenderness and hope, All We Imagine as Light is almost painfully lovely: from the nuanced performances by the trio of lead actresses, whose characters are all struggling with different desires that seem just out of reach, to the luminous cinematography by Ranabir Das (A Night of Knowing Nothing, The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs), who uses light like an Impressionist painter uses a brush. The result is that every scene in the film looks gorgeous, but especially those that take place at night—that magical time when one’s dreams feel as though they’re almost within one’s grasp.

Yet despite the almost surreal beauty of the film’s visuals, All We Imagine as Light is fully grounded in the shared realities (and complexities) of urban living and modern romance. There are no easy answers to the complicated questions these three women ask themselves and each other, but sometimes the conclusions that are the most difficult to arrive at can also be the most satisfying—and All We Imagine as Light is an incredibly satisfying film.

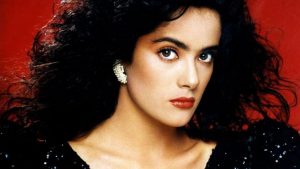

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl (Rungano Nyoni)

In her narrative feature debut, I Am Not a Witch, Zambia-born, Wales-raised filmmaker Rungano Nyoni made a powerful statement about the deep-seated misogyny that continues to pervade modern culture in the guise of ancient tradition. That film was a visually stunning satire centered on a young girl accused of witchcraft and sent to live in a “witch camp” with other such ostracized women, where they were attached to large spools of ribbon and trotted out like tourist attractions by the man in charge. For her follow-up, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, Nyoni once again examines how society uses tradition like a barbed-wire fence to keep women in their place, this time by focusing on the funeral festivities of a man accused of sexual assault by his younger female relatives. Incisive and angry, with flashes of dark comedy throughout, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl provides a scathing critique not just of the men who wield such abuse as a form of power, but the women enablers who allow them to do so, sans punishment, for the sake of maintaining respectability.

source: A24

The film opens with our protagonist, Shula (Susan Chardy, in a magnetic debut performance), coming home from a friend’s fancy-dress party. Suddenly, she sees a body lying by the side of the road and stops her car to investigate. As if unexpectedly encountering a corpse wasn’t traumatic enough, this happens to be a corpse she knows: it’s her uncle Fred, who sexually abused her when she was a child. And Shula isn’t the only victim in her middle-class Zambian family; her cousins Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela) and Bupe (Esther Singini) were also assaulted by Fred. Their mothers know, and while they claim to care about their daughters, they seem to care more about putting on a big funeral that masks Fred’s myriad crimes with an air of bourgeois respectability. As part of the proceedings, Shula is forced to dress a certain way, wait on her various male relative’s hand and foot, and even dictate a gushing funeral announcement that makes Fred sound like the second coming instead of the serial predator he was.

Soon Shula discovers that Fred’s widow is not only barely out of her teens, but also has been left with a flock of children to raise; she couldn’t have been more than 11 or 12 when she first gave birth. But Fred’s surviving family would rather blame the young widow for Fred’s death than see her as the victim she really is; they demand monetary restitution for the supposed crime of not taking good enough care of him and then promptly kick her and her children out of their house. During the funeral, Fred’s sisters won’t even let the widow eat or go to the bathroom in the house, something that Shula refuses to accept. As it becomes more and more difficult to balance the duties expected of her by her family with her desire to do what is right by Fred’s surviving victims, Shula does begin to resemble the titular bird, whose distinctive clarion call is a warning to the rest of the creatures on the savannah that danger is coming.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl presents Shula as more modern and less tradition-minded than her older relatives, yet instead of growing to better appreciate her family and their traditions over the course of the film—something often seen in such stories about young people reckoning with their cultural identities—Shula becomes more and more alienated by them. And who can blame her? As Shula faces the traumatic events of her past over and over again during the funeral festivities, dreaming her younger self back into existence each night, her older relatives simply try to forget these things ever happened at all. But even if Shula was capable of forgiving Fred for what he did, she cannot forget—nor can she forget the other victims who must live with the memories of his crimes even after he is gone.

A film that is almost incandescent with the fire of female rage, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is not nearly as visually striking or narratively complex as I Am Not a Witch, but that doesn’t mean it is lacking in emotional impact. Here, sound is of utmost importance: the cavalcade of overlapping voices that seek to drown each other out so that ill cannot be said of the dead, the silence that permeates this middle-class culture and keeps secrets not buried so much as pushed into the background, the solemn song the elder women sing to comfort their anguished daughters in one of the film’s most poignant moments. Cinematographer David Gallego guides a smoothly moving camera in and around the various gatherings of people, giving the film an intimacy and an immediacy that only adds to its considerable power. On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is not an easy watch—how could it be, given the darkness of its subject matter—but it is a rewarding one, with a final scene that will haunt you long after you leave the theater.

All We Imagine as Light and On Becoming a Guinea Fowl screened as part of the Main Slate at the 2024 New York Film Festival. All We Imagine as Light opens in select theaters in the U.S. on November 15, 2024.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.