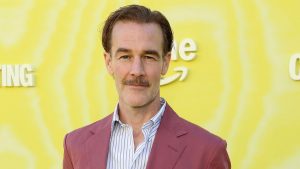

Seneca (John Malkovich) just won’t shut up. Even when he has a sword pointed at his throat. Even when his lackeys are slitting his wrists. Even when he’s lying on the cold stone floor, waiting to die. The dude has too much to say — or, rather, he thinks he does.

The dubiously arthouse black comedy Seneca: On the Creation of Earthquakes, a German production helmed by Robert Schwentke, represents the latest film in which John Malkovich gets to yell obscenities at people. It’s a quixotic postmodern farce masquerading as a period drama. It’s a labored attempt to allegorize modern politics from the fall of Rome under sadistic idiot Nero (Tom Xander), who is properly depicted here as a mentally unstable, pale-faced Reddit baby. Seneca is a fascinating film, but I promise, it’s more fun to read about than it is to watch.

Seneca The Younger

The role of Seneca was unquestionably written with Malkovich in mind. (Schwentke previously directed him and Mary-Louise Parker in the retired assassin spy comedy RED.) As Malkovich’s performance seeps in, Seneca comes to resemble a sort of bizarre black box theater performance — by the end of the film’s nearly two-hour runtime, one gets the sense that they’ve just witnessed a one-man show, despite the presence of other actors. Those other members of the ensemble hardly act anyway and instead merely hover around Malkovich. They’re poised and attentive but mum — a bit like meerkats, which stand sentinel while their comrades’ heads are buried in the sand foraging for insects. Malkovich here is in full-on insect foraging mode, and he makes grubby little beetle breakfasts out of each and every monologue he’s given, whether it’s a long string of profanities or a pontification on the sorry state of the Roman Republic.

source: Weltkino Filmverleih

Seneca has ample reason to hate the country he serves. In a brisk, entertaining historical clip show at the start of the film, we see how Seneca helped to royally fuck over Rome and its people. As the chief advisor and speechwriter of the little shit Nero, Seneca thought he was counseling the ruler in the importance of virtue, honor, mercy, and wisdom, but in reality, he was just writing pretty words to excuse the emperor’s barbarism.

Nero hardly pays attention to the doddering old man. After the death of Nero’s mother, Agrippina (Mary Louise Parker), Seneca’s voice diminishes further still in court until, finally, Nero orders him killed. The majority of Seneca takes place at the end of the philosopher’s life, in the days and hours leading up to his emperor-mandated death by suicide.

Malkovich > Style > Substance

As the commanded-to-kill-himself philosopher, Malkovich is frustrating and brilliant. He plays Seneca like a Polonius figure, babbling incoherently at great lengths until someone has the courtesy to stick a dagger through the curtain. Some of what he says holds merit, but in the bigger picture, his words are empty and vacuous, his philosophy inane and ignorant, and his life small and meaningless.

source: Weltkino Filmverleih

The death of Seneca is a tragedy frequently depicted in great art, be it sculpture, woodcut, or paintings. No frame of Seneca is as beautiful, complex, or well-organized as the finest portraits of his death, but the meager joys to be found in the film come from that juxtaposition. Schwentke’s comedic take on the character’s death comes from exposing him as a buffoon at every turn. It’s as though he begins with a chiaroscuro oil painting of Seneca’s death and keeps zooming out until Seneca’s death loses all sense and meaning. However annoyingly his role may be written, Malkovich is perfectly cast as this ghostly moron. His Seneca is a poor sap wailing for exoneration even as he lies on the stone floor gasping for breath.

Of so little substance is the film around Malkovich that Seneca doesn’t really need other characters to drive the plot forward. Nevertheless, the cast is rounded out by Geraldine Chaplin and the late Julian Sands as high-society friends of Seneca’s, and Andrew Koji also stars in the ridiculous but thankless role of a soldier assigned to make sure Seneca dies by dawn. Schwentke’s script, which he co-wrote with Dog Eat Dog scribe Matthew Wilder, does well to supply its lead with a meaty role, and it knows the trajectory it wants to take, but it’s dreadfully dull even in its comedy, and it can’t even be saved by a mid-film performance of Thyestes acted out by people wearing Mr. Meeseeks costumes. There’s style for days in Seneca but only enough nourishment for about 20 minutes.

Alright, Fine, We’ll Talk About The Trump Allegory

Seneca is interesting despite itself. Every creative instinct the movie bears proudly is intended to dispel interest in its characters, their plight, and their world — this is ancient history, we’re constantly reminded, in all its absurd pomp and grandeur. The characters perform in a villa in the middle of the desert, signifying their remove from civilization. When they ride on horseback back to the city, they pass by oil refineries and power lines, like specters haunting places that have long since forgotten them.

Yet Seneca is also distinctly aware of its story’s parallels in modern times. As farcical as its story can be and as preposterous as its characters are, Seneca also has one foot in the genre of contemporary political commentary. Nero, with his wild temperament, wanton ignorance, and bad hair, reminds us of man-children rulers like Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, Alexander Lukashenko, and Boris Johnson. His unchecked power, predilection for violence, and fixation on his own image might remind us of images of a shirtless Vladimir Putin on horseback. Imagining Nero as an angry 21st-century boy does the film as much good as it does ill, providing an entertaining and atypical read on one of history’s greatest monsters and inviting connections to the insecure masculinity of today’s despots.

source: Weltkino Filmverleih

At the same time, though, it’s a sophomoric read on contemporary authoritarianism, propositioning that the tyrant is merely a baby with severe mommy issues who rules through fear, someone who surrounds himself with yes-men and tortures, rapes, and murders to get his way. All of these criteria might have been true a hundred years ago, but Seneca falls short of allegorizing the slick, sophisticated, nature of modern autocracy.

The sole compelling idea the film manages is its characterization of Seneca. The idea that this advisor, speechwriter, and enabler of one of history’s greatest monsters is eventually swallowed up by the animal he fostered to power — that’s drama, baby! In Seneca’s modern framing, indifference to its contemporary mise-en-scène, and this central narrative of a man killed by a machine of his own making, the film reminds us that history’s monsters did not grow from the soil unnurtured. Seneca is reimagined as a Stephen Miller-type character, a reedy, insidious twerp who became totally subservient to the brutal regime on whose boots he slobbers. You may watch Seneca and come across with a totally different take — maybe you think Seneca is a tragic figure. Maybe you think he’s poignant. Maybe you feel sorry for him. Maybe you think he’s funny. My only suggestion is that as a tragedy, the film is basic and, at worst, redundant; as a comedy, though, it’s at least interesting.

Conclusion: Seneca: On the Creation of Earthquakes

In my opinion, the rotten core of Seneca is Seneca himself, and Schwentke, to his credit, does not try to hold your hand through his exploration of this complicated figure. Seneca talks nearly nonstop for two hours, his speech full of airy repetitions, aphorisms, and half-formed thoughts, and Schwentke lets Seneca’s voice fill the room. The film might not be very good — it’s in my opinion very tedious — but of all the arrows it fires, that one strikes the heart.

After a time, Seneca feels less like a character study than it does a trial — one of those Kafkaesque ones, where the jury is already stacked against him. We know Seneca dies at the end of this, one way or another — the tragedy is the inevitability, while the comedy is watching him rant and rail and squirm against the boot coming down to squash him.

Seneca: On the Creation of Earthquakes is a German release and does not yet have U.S. distribution.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema – get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.