The most popular thing to do when watching an anthology film is finding the connective thread. Whether they’re exercises in genre cinema or quirky odes to magazine journalism, the inherent appeal of three or more stories playing to you in bite-sized format is running your fingers along a strand that can then be tied around the whole experience like a tight bow. Well dear reader, believe me there’s enough material in Yorgos Lanthimos’ Kinds of Kindness to wrap itself all the way around your neck and squeeze. Unfortunately, a case can be made that Lanthimos suffocates the potential and life out of his baby as well.

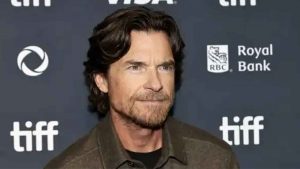

The threads entwining here are multitude: they’re three stories of submission and humiliation in the name of love; tales of delusion and destruction; even the actors are largely recurring. Emma Stone, Willem Dafoe, Margaret Qualley, and perhaps most impressively, a full range of Jesse Plemons’ sad sacks, get to unpack characters who time and again succumb to whatever vice is at hand: micromanaging bosses, sex cults in want of a messiah, and even a sampling of cannibalism is on the menu for these folks.

Yet the true and greatest common denominator is Lanthimos himself, and the palpable joy he seems to be savoring after achieving “just say yes” clout in Hollywood. How can he not after directing two consecutive indie box office darlings that also won major Oscars? And to be sure, The Favourite and Poor Things deserved their accolades, with The Favourite being my favorite film of its year.

That success has bred an elite status for the Greek filmmaker, allowing him the space to replicate the idiosyncratic cynicism of his earlier native films which married surrealist humor with outright nihilism—but this time he gets to do it with movie stars. And you know what? Good for him for getting there. But to look for the point of Kinds of Kindness is like looking for meaning in a particularly obscure barroom joke. Its appeal matters only to the bon vivant muttering it into his cups, and his sense of humor has already gone three sheets to the wind before the thing’s even started.

The first gag, called “The Death of R.M.F.” (which like the other two fables features totally unrelated characters with the same initials) is also the strongest. With bleakly amusing schadenfreude we are introduced to Robert (Plemons), a man who for over a decade has allowed his convivial but demanding boss Raymond (Dafoe) to manage every facet of his day. This also doesn’t just apply to the office. Robert begins each morning by looking at a precise schedule of what and where he’ll eat, when he’ll make love to his wife Sarah (Hong Chau), and whether he’ll even try to become a parent. Robert seems strangely accepting, if not pleased, with this arrangement. That is until he’s asked by Raymond to (probably) kill a fellow with the initials RMF by T-boning his car that night.

If Robert’s predicament is darkly preposterous, it pales in comparison to that of Daniel in “R.M.F. is Flying,” another unhappy Plemons protagonist who is at first depressed because his wife Liz (Stone) seemed to be lost at sea. But he becomes further irate when she is discovered on an island ruled by dogs. He tells his police partner Neil (Mamoudou Athie) that he thinks the Liz who’s come back into his home is actually an imposter, and fumes over her inability to remember his favorite song. Ultimately, he believes the only way to bring his real wife back is to test the fidelity of the supposed doppelgänger.

Finally, Plemons and Stone play characters on the same page in “R.M.F. Eats a Sandwich,” a tale about a sex cult that may or may not be on the verge of discovering a messiah with the power to raise the dead. That’s at least what their characters Andrew and Emily are told by their master Omi (Dafoe), who on special occasions takes both of them to bed in quick succession in thanks for their loyalty. Yet when Emily’s husband (Joe Alwyn) and child from a previous life show up… things get complicated.

Like all anthology films, not all the stories are created equal. Each has its moments of dark and understated bemusement, such as when the allegedly faux-Liz attempts to arouse her copper husband by spanking him with his nightstick, and in the next scene Plemons has tears in his eyes while recounting the experience. But generally, the only one that works as a complete story is the first where we examine the truly pathetic depths Robert will sink to make his finicky boss happy. In their own ways, each story is about love and how to realize that true ideal—be it for a spouse, an employer, or your cult guru—Lanthimos believes one must completely defile the self… Maybe?

I’m not honestly sure Lanthimos is really suggesting that love is a many un-splendid thing. Rather the filmmaker seems amused at how depraved his imagination’s sense of humor can turn in a tryptic of stars and characters accepting their self-abasement. The results are a comedy where, thrillingly, you never really know what the next scene (or even shot!) might yield. Yet we’d argue that the anticipation for a devastating payoff is only fully rewarded in the one with Plemons breaking into the home of his replacement for Dafoe’s affections. The cult story also has a deliciously ironic punchline but takes a long time getting there.

Kinds of Kindness was apparently filmed during the long post-production process of Poor Things, a film which Lanthimos spent the better part of a decade refining and tinkering with collaborators like screenwriter Tony McNamara and Stone herself. Conversely, Kinds of Kindness feels very much like the rapidly pursued, and perhaps somewhat undercooked, palette-cleanser Lanthimos needed to decompress. It is a return to Lanthimos’ roots, not only in terms of sadism after the uncharacteristically optimistic Poor Things, but also as a true-blue, economical indie filmed in and around New Orleans over a handful of weeks.

Despite cinematographer Robbie Ryan returning after developing the intentionally disorienting, fish-eyed style of The Favourite and Poor Things, Kindness has a muted naturalism to it with the cinematography rarely calling attention to itself—which makes the bizarre scenarios the actors find themselves in all the more unsettling and occasionally hilarious.

The piece thus becomes a showcase for the performers, with Plemons probably getting the chance to display the widest range in characters, even as the project acts as a specific vehicle for Lanthimos’ favorite muse. Emma Stone, indeed, revisits the fearlessness and intelligence she radiated in Poor Things and The Curse last year, with her characters in the second two Kindness shorts getting some, uh, meaty high-stress moments that it would be a spoiler to explain further. Suffice to say that while the movie is largely marketed on her inexplicably hypnotic dance moves, much of the film is like an interpretive solo for her performative left-field sensibilities.

Dafoe is probably my favorite though, just because his transition between playing loving father to variations on the creepy and overbearing father figure is the most subtle and perhaps human.

All do good work, but it’s in service to something that feels less like a fully realized film than an exercise in the director feeling his oats. There are moments of brilliance in Kinds of Kindness, and many more of sheer indulgence and off-putting self-congratulation. That, too, might be by design from a filmmaker who clearly has an audience of only one in mind, and now has the ability to get a star-studded cast to play to that single seat. Fair enough, but next time it might genuinely be a benefit if he’s forced to at least consider a few others in the auditorium, because most of them are going to leave Kindness severely disappointed.

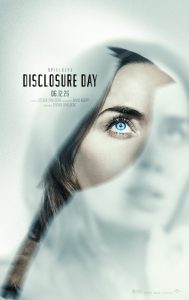

Kinds of Kindness is in theaters on June 21. Learn more about Den of Geek’s review process and why you can trust our recommendations here.

The post Kinds of Kindness Review: Yorgos Lanthimos and Emma Stone Let Freak Flag Fly appeared first on Den of Geek.