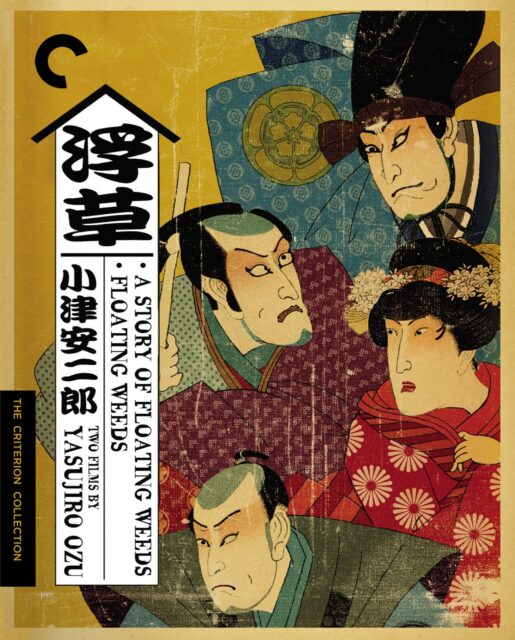

The post Home Video Hovel: A Story of Floating Weeds / Floating Weeds: Two Films by Yasujiro Ozu, by Scott Nye appeared first on Battleship Pretension.

Though his titles (which caught every end of the seasons, though never winter) often verge on the interchangeable, and his plots were so familiar that three of them feature Setsuko Hara as unrelated young women named Noriko facing pressure to get married, writer/director Yasujiro Ozu only formally remade one of his films. In transforming his 1934 silent film A Story of Floating Weeds into the catchier, only-slightly-more-modern 1959 film Floating Weeds, Ozu brought sound, color, expanse, and twenty-five years worth of personal and artistic experience. The style that by 1959 was routine and expected was in 1934 just finding its footing. It was fresh in 1934 because it was new; it became fresh again in 1959 because it was challenged.

Both films tell the same story, in much the same way – an itinerant actor returns to a small town where, decades prior, he had an affair with a woman with whom he had a son. To spare the boy the embarrassment of his father’s profession, the actor poses as the boy’s uncle each time he’s been back, all the while sending what money he can to support his son’s education. In this latest visit, the actor’s mistress discovers this, and seeks revenge by way of seducing the son, now practically full-grown. While the actor and the boy’s mother discuss the possibility of formally coupling, the chasm between them is further wedged by the mistress more directly, but more lastingly by what her scheme’s and the young man’s growing affection for her reveal in all of them.

While the subject matter and trajectory are familiar to even Ozu newcomers, the flavor here is quite different than a summary can quite account for. A sense of anger emerges from each, in varying directions, but most especially from the actor, whose rage towards his son over the relationship with his mistress comes not from jealousy, nor an overdeveloped sense of protection, but from a very deep-seated self-loathing. Each is the rare Ozu picture to let emotional, even physical violence emerge from the domestic drama, which, in conjunction with it being the only story he directly revisited twice, calls to mind questions as to just how closely Ozu related to it. Ozu is, obviously, in the same general profession, putting on plays to amuse an audience, and like the actor, he never married, living instead with his mother until she died in 1961; he passed away two years later, four years after the completion of this film.

Whatever the origin of it, the effect is strikingly unique. When pitted against Ozu’s slightly-removed, static style, the melodrama can feel unmoored at times, disengaged rather than asking us to look closer and drawing us in through calm meditation. In his commentary track for Floating Weeds, Roger Ebert notes that Ozu’s films leave him feeling at peace, comparing unfavorably the raised heartbeat and constant excitement he gets reviewing Hollywood films. Yet I do not leave either Weeds film in peace, nor in excitement, but rather shaken and disturbed by the tenor of the film, its desperate wrath and deep, middle-of-the-night sense of terror and hatred. For that reason, I have never quite warmed to them, nor do I quickly expect to, yet their distinction within his oeuvre helps color the widely-held belief – as pointless as it is inaccurate – that his films are all the same. Even the one time they nearly are, they quite are not.

At spine 232, the films have been in The Criterion Collection for quite some time, over twenty years, but are only just now making it to Blu-ray. Both films are packed onto a single disc, but show no clear evidence of compression artifacts (at a combined running time of 205 minutes in Academy ratio, and one film being black-and-white, I had little reason to fear, but one never knows). A Story of Floating Weeds is derived from a high-definition master supervised by Criterion’s Technical Director Lee Kline. It’s unclear when this was produced, but it shows some signs of age, not the product of compression, just an inherent lack of resolution, and no noted or major restoration work undertaken. It’s not overly problematic by any stretch, and only in comparison to more contemporary 4K restorations does it stand out. Contrast is excellent, as is grain structure, and it’s plenty vibrant and luminant.

Floating Weeds is more technically impressive, coming from a 4K restoration by Kadokawa Corporation. I reviewed the Masters of Cinema edition when it came out nearly twelve years ago, and the jump in clarity and quality is considerable and quite immediately evident. Detail is much finer, colors are much more pronounced, and contrast is more carefully managed. Unfortunately, the new transfer has the same inherent flaw that one did – skin tones are a little pale, and it all leans a little greenish-gray. Compared to Criterion’s 2004 DVD transfer, there’s no question the technical merits have massively improved, but the colors in that edition are quite a lot more convincing, especially as they more closely resemble those of two other Ozu color films – Equinox Flower and Good Morning – that I’ve seen in both high-definition digital versions and 35mm prints, and which present a very different vision of Ozu’s approach to color than this transfer does (I have a less robust memory of the three other Ozu color films and how they fit into this). What’s further unfortunate about the approach to this disc is that it differs greatly from what is on The Criterion Channel, which more closely resembles their DVD edition and my experience with the aforementioned other Ozu color films. That version, albeit in a lower resolution, is bright, robust, quite pleasing to look at, and seems well suited to Blu-ray, even if it may not quite have the full technical merits of this. Whether Kadokawa had any special insight into his approach on this film, and felt this color timing was more accurate, I could not say, only that the result still feels a little unnatural and displeasing. It is at least, on balance, considerably better than MoC’s.

A Story of Floating Weeds features a score by the great Donald Sosin, and audio quality on Floating Weeds is crisp, clear, and without issue.

Supplements are limited to the aforementioned commentary track by Ebert on Floating Weeds and one by Japanese film scholar Donald Richie on A Story of Floating Weeds, both from Criterion’s original DVD release. While commentary-only discs are common to several other labels, they’ve become incredibly rare for Criterion, to the point that a shopper may look at them as too little value, quite the opposite experience from actually listening to them. Both Richie and Ebert bring a wealth of knowledge, but also perspective and humility. Ebert especially admits he isn’t nearly as knowledgeable as Richie or David Bordwell, another historian who wrote extensively on Ozu, before nevertheless identifying several key insights into Ozu’s style and themes.

A booklet is also provided with a fine historical overview from Richie.

With relatively few Ozu films on the American high-definition market – Criterion has it cornered, and this is only their sixth such release – I have to confess some disappointment in this new edition, most especially surrounding the color timing of the Floating Weeds transfer. It could simply be that I’m wrong, and this color is more accurate, which would make this release invaluable, but given the significant discrepancy between it and what’s on The Criterion Channel, it’s difficult to immediately endorse it.

The post Home Video Hovel: A Story of Floating Weeds / Floating Weeds: Two Films by Yasujiro Ozu, by Scott Nye first appeared on Battleship Pretension.

The post Home Video Hovel: A Story of Floating Weeds / Floating Weeds: Two Films by Yasujiro Ozu, by Scott Nye appeared first on Battleship Pretension.