Hollywood. Tinsel Town. The Business. As movie geeks we love to consume its products while frequently not linking them very much. Then we argue about them online with others just like us, but how did it all begin? Why did it all begin? And how did we arrive where we are now? What was this Studio System we hear so much about?

Hollywood History returns to shed some light on it, back from the wreckage of our old site.

Hot on the heels of our entry talking about the many entanglements between The Mob and Hollywood, we go back, way back. Back into time. Today, we cover the establishment of Hollywood itself and the creation of the famous studio system that would shape the Hollywood we know today.

Go West!

Adolph Zukor, Louis B. Mayer, and three brothers Jack, Harry, and Sam Warner, were all Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. They had settled in America in the Northeast. As theatres catered primarily to working-class people and were concentrated in urban areas, a lot of the clientele were Jewish, Italian, and Slavic immigrants.

Over time the ownership of these theatres came to represent part of their clientele. The Jewish community in particular at the time, as some cinema scholars theorize, was highly enthusiastic about the potential for theatre as their Book Of Deuteronomy instructed them that:

“Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.”

This discouraged sculpture and even painting. Theatre, however, was not included in this. This was the very spark that lit the fuse of what would become the entertainment industry today. The whole thing is down to the interpretation of a clause!

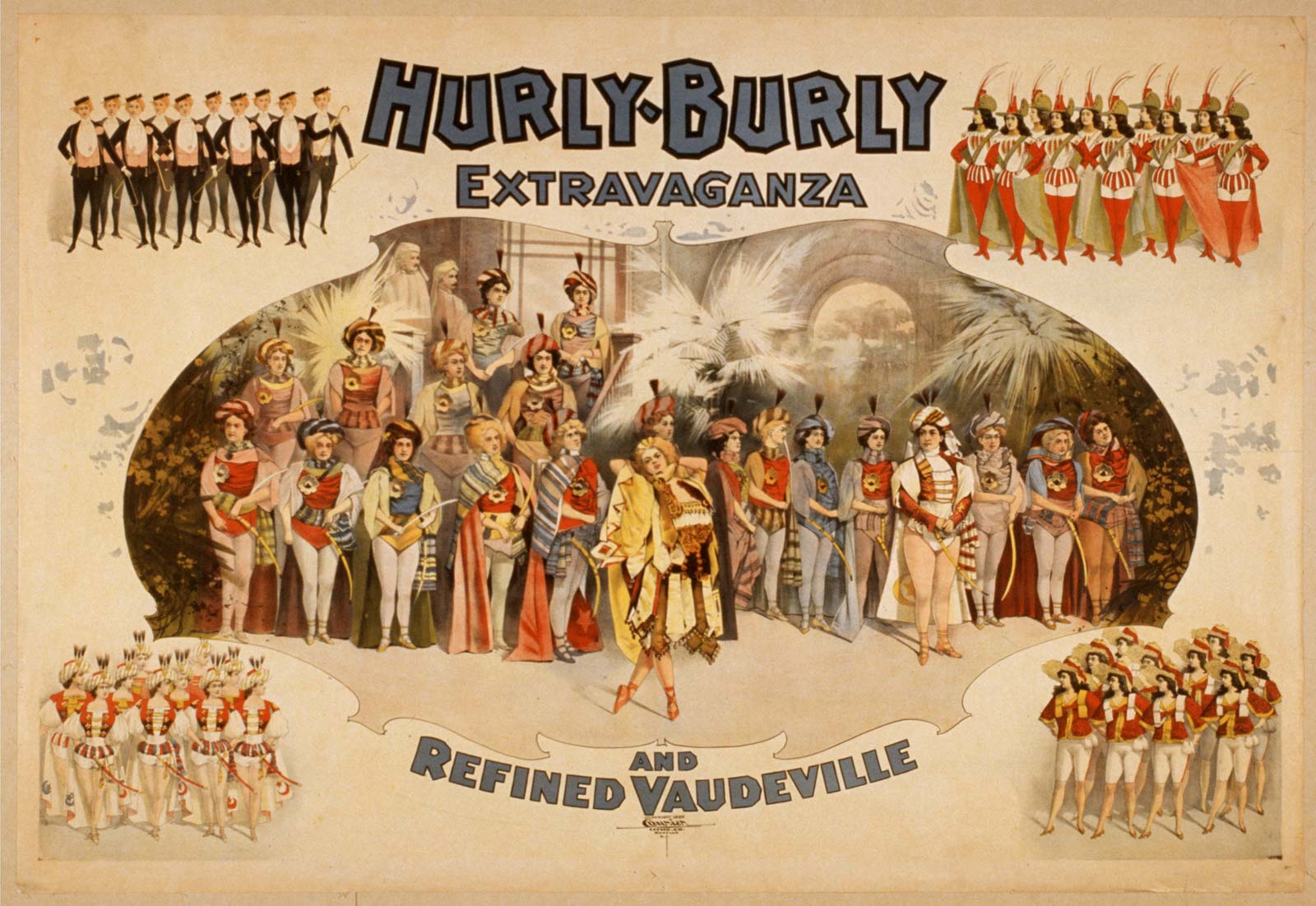

Vaudeville and burlesque were the go-to acts back then, but owners quickly realized that showing film presentations in their theatres was vastly more profitable than paying live acts to perform, and they could run the show more times a day. Their biggest problem was supply. They simply could not get enough movies as the US industry was in its infancy.

Theatre owners attempted to import movies from bigger, more established markets in Britain, France, Italy, and Germany. However, there was a problem in the shape of Thomas Edison.

Thomas Edison owned most of the major US patents relating to motion picture cameras. The Edison Manufacturing Company’s patent lawsuits against each of its domestic competitors had crippled the US film industry, reducing production to just two companies – Edison and Biograph. He was notoriously litigious and when theater owners began importing movies made on technology Edison felt infringed on his copyright, he sued them.

If they didn’t use Edison machines and films exclusively, they would be subject to litigation for supporting filmmaking that infringed Edison’s patents. So some enterprising theatre owners turned their eyes West, away from Thomas Edison and his New Jersey home, and his lawsuits.

Slowly they began to settle in and around Los Angeles. It was about as far away as you could get from Edison, meaning they could practice their craft without fear of endless litigation.

The Southern California weather brought sunny and cloudless skies year-round. This was essential for both light and for continuity. Hollywood was 15 miles inland and towards the center of the Los Angeles basin so marine fog would not be an issue, meanwhile mountains, forests, a desert, and a coastline were all on hand, meaning the local area could double for just about anywhere on Earth.

Hollywood was simply the beneficiary of location.

Meanwhile, as World War I raged across Europe with America not yet involved for a number of years, Hollywood benefited. The film industries of Britain, France, and Germany were highly restricted by the war. By the time the war was over, Hollywood-made motion pictures were America’s fifth-largest industry.

Live By A Code

Before and after the war Hollywood films had always been in sharp contrast to the movies a lot of the rest of the world was making. The German industry was an extension of the Expressionist art movement which German movies tried to reflect. States of the mind such as anxiety or madness were depicted in movies heavy on dialogue and strange camera angles.

It remained so through the age of Fritz Lang and Robert Weine up to the 1920’s.

Russian cinema went in a different direction with a determination to reflect reality. Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin, and Dziga Vertov were among the pioneers of the montage and created a great many movies reflecting the Russian Revolution.

By comparison, Hollywood cinema was considered childish, unnoteworthy, and not considered art by professionals and critics. The audience, however, thought differently and embraced the more whimsical tales.

The tone and approach of Hollywood were also largely shaped by a code. The production code officially called the Motion Picture Production Code, was nicknamed the “Hays Code.” America, at its core, was a highly puritanical and judgmental nation with religion at the centre of its foundation.

The code banned morally unacceptable content including, incredibly, prohibiting any villain from profiting from their despicableness by having a happy outcome. All criminal activity had to be shown to be punished. Under no circumstances could any crime be represented as justified.

It prohibited showing “scenes of passion,” and adultery, illicit sex, seduction, and rape could not even be alluded to unless they were absolutely essential to the plot and severely punished by the film’s end.

The code demanded that the sanctity of marriage be upheld at all times, although sexual relations were not to be suggested even between spouses.

It forbade the use of profanity, vulgarity, and racial epithets. Prostitution, miscegenation, sexual deviance, or drug addiction were verboten. Nudity, sexually suggestive dancing or costumes, and “lustful kissing” could not feature.

Excessive drinking, cruelty to animals or children, and the representation of surgical operations, especially childbirth, “in fact or silhouette.” were similarly a no-no.

In the realm of violence, it was forbidden to display or to discuss contemporary weapons, to show the details of a crime, to show law-enforcement officers dying at the hands of criminals, to suggest excessive brutality or slaughter, or to use murder or suicide except when crucial to the plot.

Locked within these restrictive guidelines, Hollywood movies tended to take on a certain look and feel. Hollywood’s studios mainly agreed that movies should be an escape from, not a reflection of, reality. As such, they focused on storytelling.

The Big Five

Zukor’s Paramount Pictures, Mayer’s Metro Goldwyn Mayer, and Warner Brothers Pictures were the foundations. Former Warner Brothers production head Daryl Zanuck’s 20th Century Fox joined them, along with RKO Pictures from 1928 as sound started to roll out.

With the restrictive guidelines coming into force in 1934 setting this Hollywood style and approach, the system became somewhat commoditized and industrialized.

These studios were run like factories, and storytelling was their product. They were what we today call “vertically integrated” in that every single thing they needed to function was under their roof, within their control. From ideation to distribution, the writers up the front put stories through the sausage machine process right into theatres owned by these five studios.

Everyone and everything was under contract. Producers, directors, actors, writers, cinematographers, art directors, technicians, costume makers, set builders. It all came from within the studio itself.

Each studio had a stable of actors, supporting actors, and a pool of central casting extras. They owned their own vast wardrobe departments, their own technical equipment.

Mayer with his stable of stars

Studio self-sufficiency made production design simpler. Producers and art directors had their own teams of in-house artists, carpenters, costume designers, and lighting technicians. Sets, props, and costumes were often reused across multiple movies.

These studios had effectively adopted Ford’s production line techniques for filmmaking. Efficiency was high. The production line did not concern itself solely with materials either. It engulfed the actors too. Today actors flee from type-casting but back then it was the only casting.

Actors and movie stars are two different beasts, and back then is where it all started. Each studio had an internal “Star System” that identified and groomed potential leading stars. As Mayer himself once put it:

“A star is made, created; carefully and cold-bloodedly built up from nothing All I ever looked for was a face. If someone looked good to me, I’d have him tested. If a person looked good on film, if he photographed well, we could do the rest.”

Then, as now, studios were mostly more concerned with camera presence than acting ability. The studio could then shape the star, changing the actor’s name or insisting they take diction lessons or work physically on their posture. They would also receive coaching in horseback riding, dancing, singing, and swordplay.

They would have physical training to ensure they remained fine specimens of the ideal human. Armies of stylists were deployed. This was also the birth of the Hollywood cosmetic surgery industry.

Stars also had their behavior regulated by the contracts. They were to do nothing, even privately, that undermined their bankability. Studio PR executives were connected and well-funded. Scandals were immediately hushed, often with the cooperation of law enforcement and local press, with lots of money changing hands.

As the industry grew, so grew Hollywood. It was effectively a company town to rival anything Toyota would ever create in Japan. Its population surpassed 1 million by 1930.

World Domination

The Hollywood approach became the pre-eminent filmmaking style globally by force of sheer mass. The Hollywood approach, still governed by the restrictions of the Production Code in the US, held that anything that diverted attention from the story to the filmmaking process was a mistake.

One of the biggest destroyers of myth and magic was the continuity error. With final responsibility for continuity residing with the film editors the term “continuity editing” was born, and this focus on continuity eventually became known as “Hollywood-style editing” which held sway until the mid-1980s when a new generation of music view editors began to take their visual style into motion pictures.

Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists emulated the Big Five’s production practices, copying the studio system as far as they could, but possessed no theater chains of their own and relied on The Big Five for distribution.

1943-New York, NY: Movie marquee on the Paramount Theatre for the film “The Major and the Minor.” 1943.

By 1945, 17% of theaters accounted for 45% of domestic film rentals. This 17% was owned by the Big Five studios. Any theatres not in their control were made to “block book” i.e., in order to rent a studio’s A-budget films, the theater must rent a block of movies that included B films, shorts, newsreels, and cartoons. The studio system favored them voraciously.

From this, Disney was born, and its cartoons were distributed in RKO block bookings. The behemoth that would come to consume Hollywood had such a modest start.

These B-movies were frequently as popular as the A-list movies with younger audiences, and today are venerated and subject to homages such as Indiana Jones.

1948: American actor Rosalind Russell sits with her legs crossed on the edge of a wooden desk, holding a cigarette, as director John Gage (C) and his crew film a scene on the set of ‘The Velvet Touch’.

The Big Five would ship packages of 20 or more presentations including those not yet made. They would be sold on the name of the leading actor alone. This selling power is what was first meant by “Star Power.”

Non-studio theaters were the last to receive A-quality presentations, hence why a rural theater could have a movie showing as a new presentation to them that had already opened six months or more ago in a big city.

Death Of The Golden Age

The studio system was brought to an end, not by business failure, but by government action. At the U.S. Supreme Court, the United States v. Paramount verdict banned block booking and ordered the studios to sell off their theatres.

This lost a guaranteed revenue stream for the big five. Newly independent theaters only wanted winners and would not book movies that were (or had the potential to be) box-office losers.

Studios couldn’t afford to maintain the scale, and without scale, affordability fell even further. As the studio system collapsed a vicious circle was created as contract directors, actors, writers, cinematographers were shredded.

Eventually, RKO went bankrupt. By the late 1950s, the widespread adoption of television landed the second of the one-two punch that left Hollywood, as they knew it back then, on its knees.

On one hand, the ability to block book created the B-movies that inspired some of our favorite movies today. They also provided a reliable income which allowed a studio to take risks. On the other hand, did the volume cause a quality issue? How different is it from today, where averse studios can only release strong, recognized IP or risk big losses?

Is it time for the studio system to make some kind of comeback?

The old studio’s in-house “sausage machine” has been reborn, to a degree, in entities like Marvel Studios.

Now that Amazon has bought MGM, the distributor now owns the producer. Both of these are reminiscent of the “vertically integrated stack” of Hollyweood’s heyday, and MGM can blockbook its product all over Amazon’s streaming distribution channel.

Is the studio system making a comeback in a way we never imagined, through the medium of streaming?

Check back every day for movie news and reviews at the Last Movie Outpost

The post HOLLYWOOD HISTORY: The Studio System appeared first on Last Movie Outpost.