In August 2011, rioting broke out on the streets of Huddersfield. Bricks were thrown at shopfronts, windows were smashed and CCTV cameras were destroyed. The cause of the violence wasn’t explicitly the rickety Yorkshire accent of Brooklyn-born Anne Hathaway in recently released film One Day, but we can’t rule it out as a contributing factor.

Hathaway’s accent in One Day wasn’t as much bad as it was senile, forgetting for large chunks of the film who it was and what it was supposed to be doing. It went up hill and down dale with all the control of Compo in a bathtub, making pitstops in London, Ireland and South Africa along the way. Perhaps impressively, it also wasn’t the worst thing about the film.

Adapted from David Nicholls’ 2009 hit romance novel, Lone Scherfig’s film fell between two stools. Neither glossy and feelgood, nor indie and uncontrived, it failed to find the same audience as the book.

The novel’s structure was part of the problem. One Day drops in on central characters Emma and Dexter on the same date once a year for almost two decades. Over 450 pages, the conceit is energising and makes the reader turn detective to piece together what’s happened in the interim. Over a two-hour movie, the structure becomes quickly repetitive and makes the story feel both rushed and empty. The film’s whistle-stop tour of the characters’ lives flattened them rather than fleshing them out, which led to its real sticking point: Dexter.

Before we get into it, this isn’t a question of likeability – a word more overused in TV development meetings even than the phrase ‘Here’s your flat white, Tristan’. Likeability is a crutch for media execs who unimaginatively assume that audiences seek the same qualities in a character as they do in a Labrador retriever. Much more important than likeability is recognition. We don’t need to like a character to see them in ourselves and others. The companionship offered by fiction doesn’t have to be a love-in.

More or less the whole point of Dexter Mayhew in One Day is that he isn’t likeable. Handsome, privileged, entitled, unserious… he’s everything Emma Morley isn’t. She’s working class, clever, politicised and funny, and yet she loves Dexter and even likes him too. And because Emma loves and likes Dex, who is by turns weak, selfish and arrogant, the reader is prepared to put up with him to see what the fuss is about.

Through putting up with Dexter over the length of the novel, the reader comes to see him as Emma (mostly) does – a lost, kind, funny person to whom life has taught all the wrong lessons. Dexter’s always been moneyed, so has never learned what money means. He’s famous, so he’s learned that he’s more important than people who aren’t. He’s handsome, so has learned that his good looks are what make him valuable, and so on.

Time and again, Dexter draws unhelpful (if understandable) conclusions from the world. Emma sees all of that and therefore so do we. Like her, we want Dexter to be better. And because we recognise him, we know he’s capable of it. Nobody around Emma understands her loyalty to Dexter – least of all her live-in boyfriend Ian – but we understand it. That’s the attraction of their intimacy in the book; like all good love stories, it belongs only to them, and to us.

In the film, none of that knotty push-pull stuff comes across with Dexter. Jim Sturgess’ character is just the public version of the man – a cocky posh twat to whom Emma is inexcusably drawn. Despite pinning all of the book’s landmark events to the screen, the film is incapable of explaining why this particular girl would ever persevere with this particular boy. Film Dexter is neither likeable nor recognisable. He’s a cliché of playboy swagger whose occasional sadface moments reveal little but more self-regard.

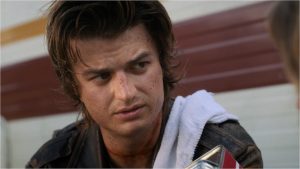

In Nicole Taylor’s Netflix series though, which has over seven hours and 14 episodes to show us the pair from every angle, Dexter’s an even better developed character than Emma. We spend more time with him in crisis. We meet his family but not hers. Played by Leo Woodall (last seen memorably as Essex boy Jack in The White Lotus season two), Dexter is everything he is in the book and more. He’s cocky, glib and occasionally hateful, but also vulnerable, underestimated and sweet.

In other words, TV series-Dexter is everything that Emma sees in him, which makes their love story sing. Woodall is excellent in the role, and has been allowed the space to make the character not likeable – that useless term – but fully human and fully recognisable.

And the Yorkshire accent? Spot-on.

One Day is out now on Netflix.

The post Netflix’s One Day TV Series Solves the Film’s Biggest Issue appeared first on Den of Geek.