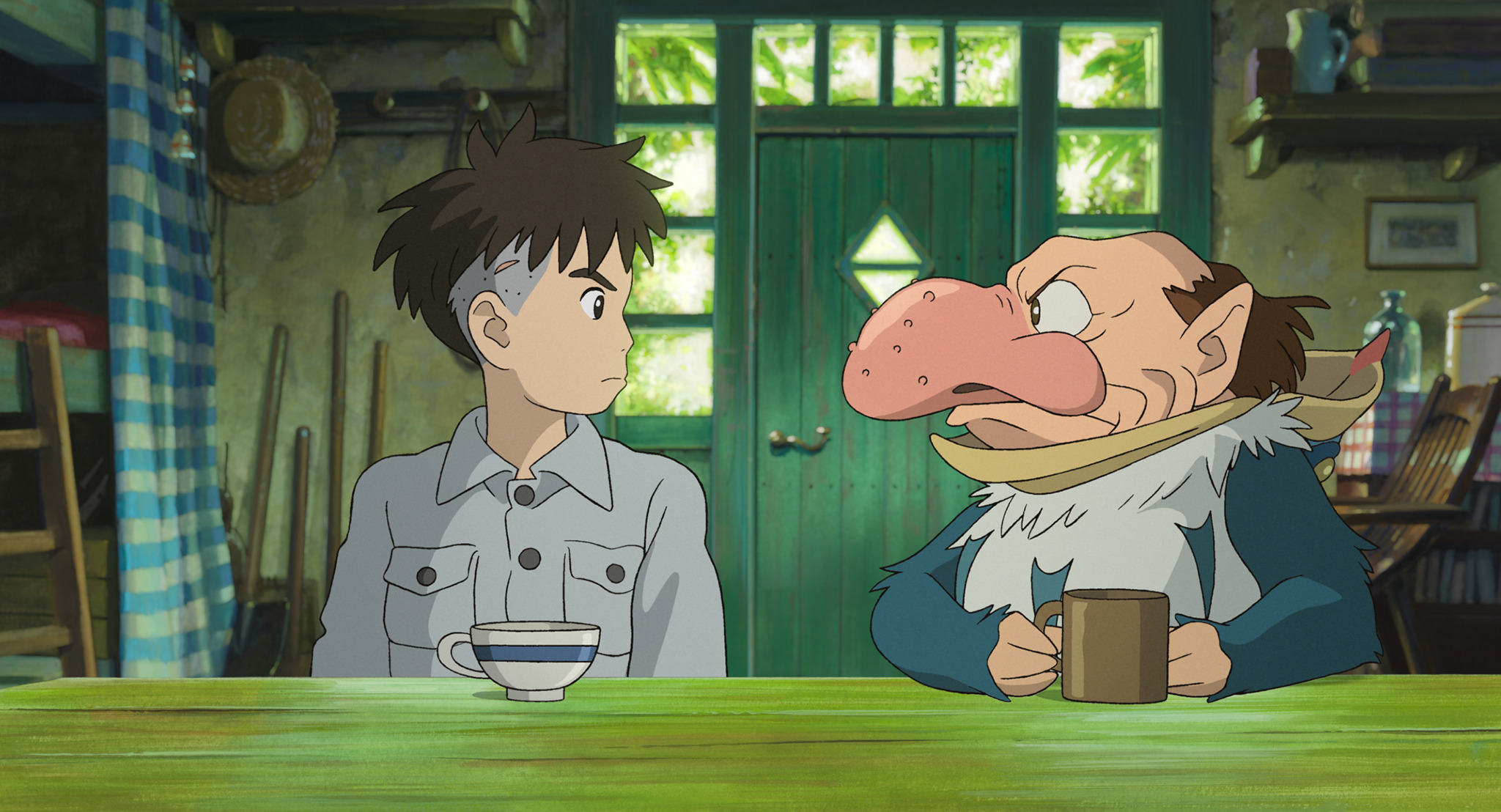

Studio Ghibli, a scrappy Japanese animation studio that was founded in the ‘80s, would go on to become an industry powerhouse that surpasses Disney’s sense of fantasy, Pixar’s emotional catharsis, and the unabashed against-the-grain individualism of DreamWorks Animation. Hayao Miyazaki’s name is often synonymous with Studio Ghibli, the animation studio that he founded with fellow director Isao Takahata and producer Toshio Suzuki. Every Studio Ghibli film is special, but Hayao Miyazaki is an anime auteur whose cinematic offerings become pop culture events that redefine animation and storytelling.

Hayao Miyazaki is a renowned voice in traditional hand-drawn animation whose movies have record-breaking budgets and take over a decade to complete. And every time, they’re worth it. Miyazaki’s feature films may seem like playful escapism to outsiders, but recurring elements and themes define the quintessential Miyazaki experience. Miyazaki’s anime oeuvre may come across as intimidating and impenetrable to newcomers. The release of Miyazaki’s potential final movie, The Boy and the Heron, means that it’s now the perfect time to experience his filmography before checking out his magnum opus. This isn’t every Hayao Miyazaki movie, but it’s a strong cross-section of the director’s career that’s laid out in a watch order that won’t leave anyone overwhelmed.

Miyazaki Newcomers

My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

My Neighbor Totoro tells the touching story of two sisters, Satsuki and Mei, who move into a new house in the country with their father while they await their mother’s recovery from an illness. My Neighbor Totoro is a magical coming-of-age story that mixes life’s challenges with adorable fantasy, which is Miyazaki’s area of expertise. In My Neighbor Totoro, it’s change itself that serves as the characters’ greatest enemy. It’s like a more fantastical and emotional anime version of The Cat in the Hat. My Neighbor Totoro is also a film that plants the seeds for Miyazaki’s love for nature, but in a manner that’s less extreme than Princess Mononoke or Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Totoro himself has become such a beloved figure in animation who’s gone on to acquire international acclaim. It’s a testament to this character’s power and why My Neighbor Totoro is the perfect gateway to Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki.

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

My Neighbor Totoro will connect with a very young crowd, and Kiki’s Delivery Service makes for the perfect follow-up that explores slightly deeper themes of growing independence and creative roadblocks. Kiki is a 13-year-old amateur witch who sets off to a new city to find her way with only her broom and cat companion, Jiji, by her side. Kiki’s Delivery Service crafts a sweet relationship between Kiki and Tombo, and it repeatedly uses Kiki’s innocence as a way to express wide-eyed awe at the world of possibilities surrounding her. Kiki is also one of Miyazaki’s best and boldest female protagonists, not in short supply in his movies. Kiki slowly finds a balance in her life as the movie explores work versus creative passion and how something as infinitely freeing and magical as flight can still be commodified and turned into a chore.

Spirited Away (2001)

Spirited Away is a breakout Studio Ghibli film that won the 2003 Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, a first for an anime movie. Spirited Away was the general audience’s introduction to Miyazaki, and it’s an acceptable place to start. However, the movie feels like a culmination of many of Miyazaki’s earlier ideas. There are shades of both Satsuki and Kiki in Chihiro, whose time in the spirit realm works better if the viewer has already been exposed to a few coming-of-age Ghibli stories. Spirited Away chronicles the young Chihiro’s dedicated efforts to restore her parents to their human forms after their egregious gluttony turns them into literal pigs. Only after Chihiro works off their debt can they all safely return home. Spirited Away connects with audiences of all ages, but its Japanese folklore influences and creepy-looking creatures become more palatable after further Miyazaki exposure. Spirited Away teases more mature themes through Chihiro’s low status in the spirit realm, but it’s still Miyazaki at his most magical and mainstream.

Miyazaki Novices

Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986)

Castle in the Sky is the first official Studio Ghibli movie, but it’s a surprisingly advanced early effort from Miyazaki. Laputa: Castle in the Sky tells an extraordinary airborne adventure that follows the same basic formula of many Miyazaki films. However, from its start, there are some distinct details that make it a more challenging and adult experience. Sheeta and Pazu, the film’s child protagonists, are lost orphans chased by sky pirates and corrupt officials who want to rob them of what makes them special. Sheeta and Pazu’s dream to locate the mysterious floating castle, Laputa, hits extra hard because these two have so little in life. It’s a magical story with a grim underlying theme about the importance of dreams and how war and commerce will slowly corrupt the world’s innocence and beauty.

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)

Howl’s Moving Castle is Miyazaki’s brooding steampunk ode to getting older. Sophie is a traditional teenager who crosses paths with the wrong witch and finds herself cursed to be an old lady unless an emo wizard named Howl gives her a hand. A curious Miyazaki newcomer may quickly seek out Howl’s Moving Castle because of its wild characters or the fact that it’s the director’s successor to Spirited Away. It’s more likely for Howl’s Moving Castle to be taken at face value and to get lost in its displays of limitless magic rather than appreciating the story’s criticisms of modernity, capitalism, and war. It’s the most chaotic of Miyazaki’s movies and the easiest to lose track of its narrative thread, just like one of Howl’s elaborate magic tricks. It feels like Miyazaki’s The Prestige in the sense that it’s a layered film that pretends to be deceptively simple.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is the director’s third feature film, and its breakout success is what actually led to the founding of Studio Ghibli the following year in 1985. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind presents a chilling version of a wasted world that feels like the result of other environmentally-minded Miyazaki epics like Ponyo or Princess Mononoke (there’d be no Mononoke without Nausicaä). Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind feels like fully-formed Miyazaki, even if it’s one of his first films, and it’s another thought-provoking adventure that strives to provoke change and promote pacifism. The eponymous Nausicaä is a courageous princess who pledges to bring two warring kingdoms to peace. Nausicaä is full of unique creatures and proudly depicts Miyazaki’s passionate aviation obsession, but the audience must wade through a post-apocalyptic wasteland to reach these brighter ideas.

Miyazaki Experts

Princess Mononoke (1997)

Princess Mononoke feels like Miyazaki’s angsty middle years in what’s easily his most violent movie that slowly descends into all-out war. It’s also the only Miyazaki movie with bloody dismemberment. Princess Mononoke is a sprawling action movie about environmental preservation that mixes Japanese folklore and demonic creatures with social activism. Ashitaka is a cursed prince who finds himself in the middle of a war for Mother Nature between demons, gods, and humankind, all of whom feel entitled to this land. Lady Eboshi is a terrifying Miyazaki antagonist likely to unnerve even seasoned Studio Ghibli fans. Princess Mononoke‘s message about the destructive, inevitable nature of the industrial march of “progress” was initially groundbreaking against a forest of shallow Disney films but is still chilling 25 years later. Just think of it as an anime version of Fern Gully but with many more demon boar gods and beheadings.

Porco Rosso (1992)

An animated movie about a fighter pilot who gets transformed into a fascist-hating pig should be a Studio Ghibli slam dunk that kids will enjoy just as much as adults. However, Porco Rosso is a surprisingly deep, dark story that’s far more than a swine’s skybound shenanigans. Set in 1930s Italy, Porco Rocco is a former World War I aviation legend who’s turned to altruistic bounty hunting. Transformative curses are par for the course in Miyazaki movies, but Porco Rocco’s pig metamorphosis is perfectly Kafkaesque while engaging in a larger condemnation of fascism and unquestioning loyalty that’s also oddly forward-thinking in its gender dynamics. Miyazaki’s endless love for aircraft is fully on display in The Wind Rises, but until then, it’s Porco Rosso that’s his biggest love letter to classical aviation. The aerial setpieces are truly unparalleled and as stunning as any spirit creature or demon.

The Wind Rises (2013)

Hayao Miyazaki has always had a fascination with how beautiful things can become co-opted into tools of destruction, whether it’s Nausicaä’s toxic foliage or Kiki’s magic-driven identity crisis. The Wind Rises is Miyazaki’s most literal version of this story, ditching the director’s standard supernatural fantasy elements for a bittersweet melodrama set against World War II. The Wind Rises is ultimately a movie about legacy and how one person’s passion can be transformed into a force of doom. Miyazaki’s love for aviation takes flight in this fictionalized account of Jiro Horikoshi’s life as he designs Japanese fighter planes that are used in World War II. The Wind Rises is Miyazaki’s most adult movie that’s unlikely to resonate on the same level with younger audiences. This is the Miyazaki movie to show young adults after they fully understand the director’s relationship with the loss of innocence and instability of self.

The Boy and the Heron will be in North American theaters on Dec. 8, courtesy of GKIDS, and in U.K. theaters on Dec. 26.

The post A Beginner’s Guide To Hayao Miyazaki appeared first on Den of Geek.